Software Is Dead — Long Live Software

"SaaSmageddon," Vertical AI & the Vibe Code Fallacy

In the span of three weeks, Anthropic shipped Cowork, Claude for legal review, and Claude for Excel. Subsequently, software equities tanked, marking the category’s largest non-recessionary 12-month drawdown in over 30 years (-34%, nearly $2T below its market-cap peak).1 Thomson Reuters had its worst trading day in history — triggered not by a competitor’s product launch, but by a set of markdown files containing structured prompts. JPMorgan titled their research note “Software Collapse Broadens with Nowhere to Hide.” Jefferies coined the term “SaaSmageddon.”

$400B of SaaS enterprise value evaporated this month. ServiceNow is down nearly 50% from last year’s peak, CRM is down 40%, and even MSFT approached a 30% drawdown. Nowhere is safe: even rumors of evidence of “AI eating X” are triggering sell-offs. A penny stock that previously sold music jukeboxes and announced a freight product caused a double-digit sell-off in logistics companies.

Rarely can a broad public market sell-off be attributed to one cause. And, of course, this is no exception. It’s first important to recognize all the reasons outside of “AI is killing all software” we might be seeing trades out of the space:

Discrete Disruption: Beyond Cowork, both Anthropic and OpenAI announced initiatives targeting the legal and financial services industries, which hit players in those spheres (such as Thomson Reuters, LegalZoom, and CS Disco) hard. Moreover, some individual software names simply failed to deliver: for example, a miss from the normally reliable Tyler Technologies (down 15%). Perhaps not too much for a 60-year-old software & services business with longstanding monopolies in govtech, now facing a brave new world of public sector AI adoption.

Hyperscaler Capex: Massive increases in AI-related capital expenditure from Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, and Amazon — forecasted to exceed $660B combined in 2026 — have spooked investors regarding when these investments will yield significant monetization. MSFT, for example, was hit thanks to both rising CapEx and Azure deceleration. We have written about this in our past essay on AI infrastructure and the idea of an “AI Bubble” here.

Sector Rotation: A general zeitgeist of overvaluation and need for a correction in technology equities (though with software now trading at roughly 4.9x EV/Revenue, it feels like overcorrection if for that reason alone). Some also speculate that stronger-than-expected economic data (e.g., the January payrolls report showing 130k jobs added) led investors to rotate from “capital-light” software into “capital-intensive” cyclical sectors like energy and industrials.

Size-Based Volatility: Small- and mid-caps generally pull down more in a market rout. Historically, this is especially true in software, a category whose aggregate EV is dominated by a few massive platforms at the top. The very long tail of sub-$5B EV software publics tends to get hit hard. During the Great Recession, NetSuite and Salesforce saw their NTM revenue multiples collapse by ~92% and ~80%, respectively.2 While — counter to popular opinion — vertical software companies have a ~20% higher mean Enterprise Value than their horizontal peers, the industries targeted by this market reaction have more vertical players with perceived un-diversified exposure.

Rational or not, the sell-off has led some VCs to publicly declare that in the wake of AI, SaaS revenue durability is challenged, if not extinct. The most bearish of “hot takes” is that vibe-coded applications will make core systems of record — or perhaps all application-layer software — obsolete.

Before getting into long-term viability, let’s dig a bit further into the numbers of the “SaaS flash crash.”

We analyzed the recent public-market SaaS drawdown, and while vertical names have been hit harder this month than their horizontal peers, the declines from last year’s highs are fairly similar. Lastly, we tried to identify which vertical sectors were hardest hit; perhaps unsurprisingly (given OpenAI and Anthropic news), the hardest-hit sectors are Legal and Healthcare, although the small n in each bucket means two hard-hit names have a particularly large impact (CS Disco in Legal and Doximity in HC).

As we highlighted above, the strongest correlation is company size (i.e., market cap). Small caps have been hit the hardest — while the delta between large and mid-cap is more modest.

Ultimately, a discrete 10% drop in software stocks tells us approximately nothing about the future of SaaS as a business model or technology paradigm. To use the famous quote attributed to Ben Graham: “in the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” 5 years from now, equity trend will surely be more instructive as to AI’s impact on SaaS. We think, however, there are a few valid conclusions we can draw in the meantime.

SaaS is Very Much Alive

While we absolutely agree that AI poses a material risk to incumbent software vendors, we do not share the consensus that “SaaS is dead” (nor that a jukebox company is a material threat to the freight market). While we hate to lead our counter-argument with pedantry, the simplest refutation of the “death of software” argument is this: AI is still software. And application-layer AI delivered in the cloud is still Software-as-a-Service.

Naturally, every major technological paradigm shift comes with new terminology. VCs, eager to signal thought leadership and capture mindshare, are as guilty of flooding the zone with new acronyms and techno-jargon as anyone else. While AI has come to replace SaaS as a shorthand, the technology delivery model SaaS was primarily meant to convey remains just as prevalent in the LLM era—even if other attributes typically associated with SaaS (such as heavy UI or seat-based subscriptions) are receding.

EvenUp, Abridge, Harvey, OpenEvidence, Rilla, MagicSchool: all AI, all SaaS. If we started calling AI “next-gen SaaS,” it might clear up a lot of confusion. When people hail the death of SaaS, many conflate the rise of a new generation with the demise of the larger underlying business model, which is stronger than ever. Calling AI the software-killer is like calling the iPhone the end of computing. In fact, like in that case, by making software easier and more accessible, AI is likely its biggest accelerant since the advent of cloud infrastructure itself.

As we wrote in our essay last week, though: just because a pie is growing, doesn’t mean everyone gets to eat. Even if SaaS growth continues unabated, the league tables in 5-10 years will almost certainly look different.

Who is Vulnerable?

In our piece last June on the threat to Vertical SaaS from AI, we highlighted three categories that we felt were particularly vulnerable:

Hyper-Narrow: Developers of extremely niche tools (in use case, more than necessarily market size) that are easily replicable with AI support. These are the nearest-term, clearest losers.

Obsoletion by LLMs: SaaS offerings that LLMs naturally subsume (e.g., Chegg, Grammarly, Dragon). That said, companies with the resources and willpower to re-invent themselves AI-first may thrive. Duolingo is talking this talk.

Hesitant Incumbents: Legacy SaaS providers who simply don’t offer AI functionality at parity quickly enough, or hold on too tightly to outmoded cash-cow products. Incentives matter. We envisioned these slow deaths in our essay on the development of intelligence systems.

We define hyper-narrow here to mean more of a function of an individual product’s scale, complexity, and defensibility versus narrow in scope. A vertical system of record, regardless of TAM, would not meet the definition. A horizontal customer service tool would. Regardless, we concede there’s genuine pressure on every app-layer company, as AI-native challengers are growing faster than ever before. And if past platform shifts are any indication of the future, it is almost guaranteed that the vast majority of incremental value will go to AI-native disruptors rather than legacy vendors. Incumbents move slowly. They can’t attract the best AI talent. They face the classic innovator’s dilemma: deciding whether to cannibalize their core business. A small subset of legacy SaaS companies will be able to weather the storm. Many will not.

And there’s a real structural threat you might call the “front door” risk. Classic software gets reduced to middleware, with agents capturing all the incremental value on top. Aaron Levie, CEO of Box, put it bluntly: every piece of enterprise software has to become a platform play because agents will do vastly more work with tools and data than people ever did. The system of record gets pushed down the stack — and that means lower growth potential and a smaller profit pool. It’s worth, of course, pointing out that the “integrate and surround” form of system-of-record disruption is by no means new. As we explored in our analysis of Vertical Software’s Integration Problem, incumbents facing this dynamic have either adapted (buy or build) or faded in relevance.

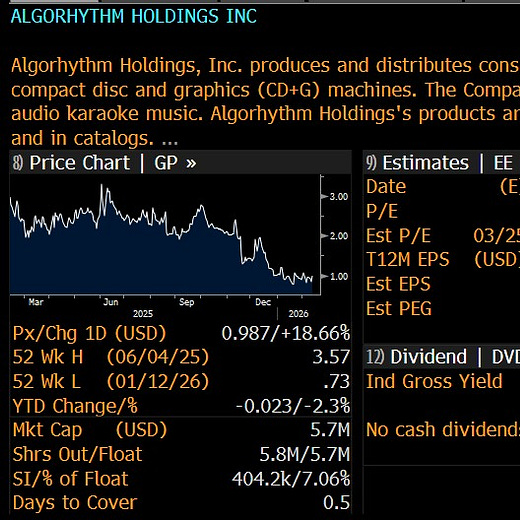

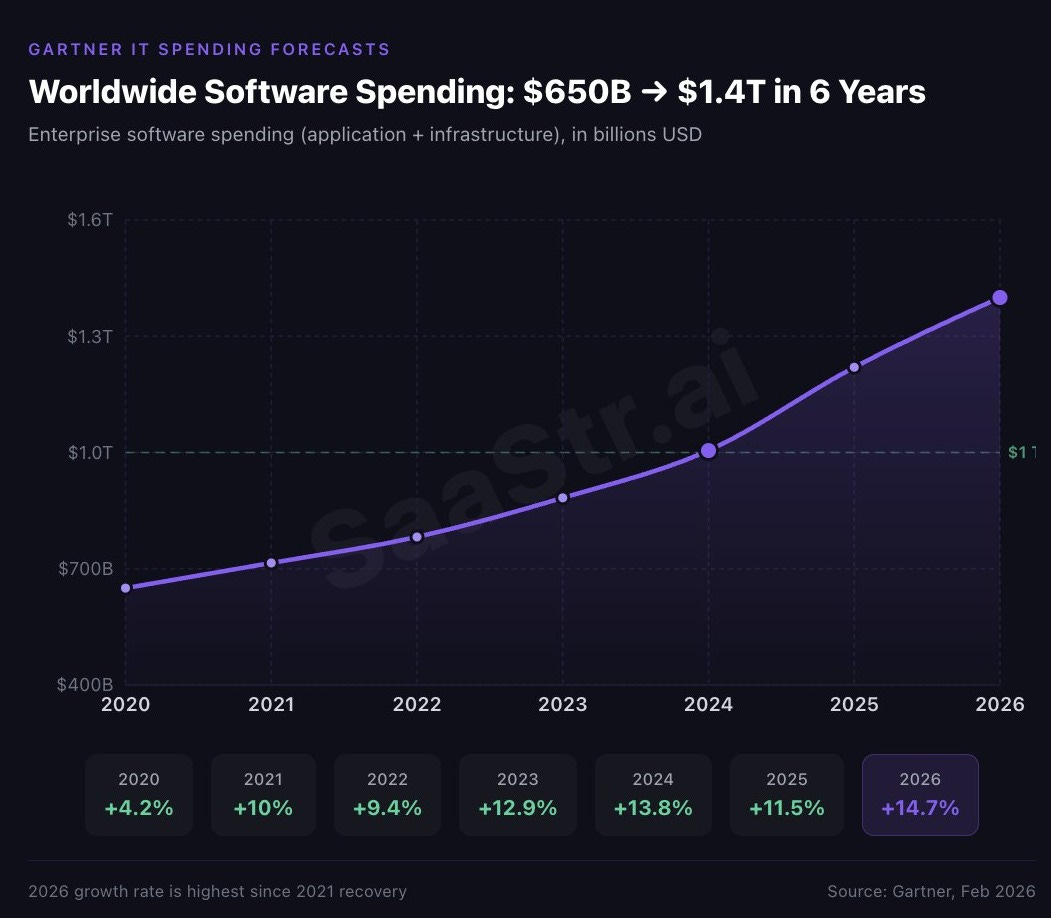

Not capturing the next phase of explosive growth doesn’t mean all growth disappears. If software were truly in its late-cycle period, it would be growing at close to GDP (it’s at least 2-3x that). In fact, Gartner expects software spending to accelerate in 2026 — the highest figure in half a decade. There is still significant growth left, even in classic cloud migrations: while 95 percent of enterprises have a cloud footprint, the share of enterprise workloads in the cloud only crossed 50% in 2025. That figure was just north of 30% eight years ago.

We’ve seen this exact movie before, and recently. Remember when the shift from on-premise to cloud was supposed to kill the enterprise software giants? Oracle, SAP, and Microsoft were all declared dinosaurs — legacy vendors that would be disrupted by nimble cloud-native startups. Instead, the successful incumbents pivoted by buying and building cloud businesses; today, they are bigger than ever. Microsoft’s revenue rose from $62B in 2010 to $282B in 2025. Oracle went from $12B to $57B over the past two decades; its cloud software business is 3x larger than the on-premise business ever was. The on-prem-to-cloud shift certainly killed many incumbents, but more importantly, it supercharged the growth of the enterprise software market. Cheaper to build, cheaper to sell, and cheaper to maintain is deflationary but also market-expanding. Global software markets were ~$200B twenty years ago; today, they're more than five times that size.

Parker Conrad, CEO of Rippling, reached the same insight, noting the impact of dramatically lower software development costs over the past two decades. AWS replaced self-hosting. Frameworks, open-source ecosystems, developer tools, and higher-level programming languages abstracted away complexity, making it possible to build in days what used to take months. The result was a Cambrian explosion of software businesses. But this did not make software companies less valuable. It increased competition, for sure. It made incumbency advantages weaker. And of course, it shortened the replacement buying cadence for many enterprises. But in aggregate, the net result is that it made software more valuable. The SaaS era that followed produced trillions of dollars in enterprise value precisely because building got cheaper. More problems could be addressed. More workflows could be institutionalized. More industries could be digitized. More customer segments (whether vertical or smaller businesses) could be sold software more efficiently.

We traced this pattern in our earlier piece on whether AI threatens vertical SaaS, examining the history of “layer commoditization cycles” from FORTRAN to cloud computing. Each cycle follows the same arc: innovation automates core aspects of a process, pushback follows as incumbents fear obsolescence, and then the market thrives with newfound productivity. LLMs are the latest iteration, and, as in every prior cycle, there will be losers, but the market as a whole grows.

The Vibe Code Fallacy

Benedict Evans made the point around the complexity of building software in his recent Stratechery interview: “I never thought that the hard part of building a piece of software that manages the thing for the other thing deep inside a big company was writing the code.” The hard part is discovering the problem, designing the right workflow, building a go-to-market strategy, and earning customer trust. And then you layer in the sheer volume of applications: the average number of SaaS tools across all buyers is 275. That number jumps to over 600 for enterprises.

It’s easy to dismiss the complexity of every SaaS app as consumable by AI, but as Evans points out, the same analogy can be applied to traditional SaaS: “they’re all a thin-SQL wrapper. They’re all just databases.” Extending the argument further, Evans adds: “It’s like the dumb Hacker News comment, ‘Airbnb is just a CMS.’ But yeah, every social network is just a CMS.”

If AI makes code cheaper, it makes the non-code moats — domain expertise, distribution, customer relationships, and what Evans memorably called “a throat to choke” — relatively more important, not less. And in the age of AI, that throat to choke becomes ever more valuable. When the output is probabilistic rather than deterministic, customers need someone accountable for the result. This is precisely why we believe the durable moats in vertical software — workflow entrenchment, proprietary data loops, and trust — compound rather than erode as AI advances.

One persistent fantasy is that enterprises will simply vibe-code their way out of buying software. Evans called this idea “delusional” in his interview, and we completely agree, especially in vertical markets. Companies aren’t in the business of building complex internal tools. Models improve extraordinarily quickly, and it would be naive to underestimate what vibe coding will achieve in two or three years. But the fundamental attitude of “let’s build internally versus pay someone to manage it” won’t change. Put aside the complexity & quality argument for a moment; the total cost of ownership will still almost always favor buying over building.

While this is especially true for vertical market companies, even cutting-edge tech startups “outsource” much of their stack. Why? Because it’s cheaper than dedicating staff to such tasks, and they can move faster on solving core problems. The net result is that cheaper-to-build software is usually cheaper to own, resulting in more prospective customers and larger markets. Companies will continue to outsource software to vendors — whether those vendors are legacy SaaS providers or new AI-native startups. We thought one particular curious anecdote around is that vibe-coding breakout Loveable just became a customer of HubSpot.

We used the analogy of super-sneakers in our earlier essay: imagine shoes that give every basketball player a lifetime of conditioning overnight. High-school bench warmers become NCAA-competitive. Even NBA pros improve. But the impact is logarithmic — the Currys and LeBrons already have a lifetime of training, and much of their edge is basketball IQ. The higher-level you already are, the less it helps. And everyone gets the shoes. The same is true for software businesses.

It’s also important to remember that digitization remains low in most vertical markets. These industries moved from pen-and-paper to Excel to off-the-shelf vertical software. And just like the SaaS revolution, many prospective vertical customers that were left behind will jump straight from having no software for certain workflows to buying AI-native platforms. We explored this adoption pattern in greater depth in our piece on Diffusion of AI across Vertical Markets.

We’ll share an anecdote that reflects a similar challenge we often see, even among the largest prospective vertical buyers, and one most tech-forward people have little exposure to. We were talking with a multi-billion-dollar construction materials business that had three different ERPs. Why? They were growing quickly, both organically and inorganically, and when they couldn’t figure out how to migrate off their multi-decade-old system, they decided to keep it installed for certain regions and workflows, buy a new system for organic growth, and eventually not bother replacing the third system they inherited from M&A. While they have no plans to change this IT stack, they are actively evaluating and purchasing new pieces of Vertical AI. These industries are not leapfrogging to prompt-engineer their own tools anytime soon, but they are now active buyers of new tooling. That same company just bought its first CRM (though they’d call it something else), along with a voice-first revenue acceleration stack.

What Comes Next

Not all software is created equal, and the panic is treating it as monolithic. Ben Thompson made a key observation in his Stratechery interview: “The destruction and the value creation are not simultaneous in time. First, there’s a lot of destruction, the unbundling aspect, and then people are freed up to figure out the new thing, and that’s when the value creation happens.”

We are still quite early in the destruction phase, despite the market panic and stock prices cratering. Some vertical software companies will die, though we think the durability of those names is far higher than that of their horizontal peers. Some of the next generation of vertical AI companies will be built on the rubble, but most of them will be built on green fields. The market, by definition, cannot expand if it’s just ripping and replacing legacy vendors. And it’s not hopeless for existing legacy vendors: incumbents with distribution and trust advantages can capture their fair share of AI revenue, too. The recent history of vertical profit premiums suggests the market already prices in the durability advantages that vertical incumbents enjoy.

As we explored in Dude, Where’s My Moat?, the immutable primitives of software defensibility are workflow and data. Speed is a compounding advantage in the early days of a category, but it is not a durable moat. At scale, almost all companies slow down — and that’s where data gravity, brand and trust, and platform lock-in take over. For Vertical AI, the path to defensibility runs through what we call the System of Intelligence: becoming the authoring layer for high-value workflows, building data loops from customer usage, and expanding into adjacent products that compound switching costs. The startups that build toward these moats early will be the ones still standing when commoditization arrives. Equally, the incumbents who survive—and perhaps even thrive—long-term are those who leverage brand and data gravity to build a durable moat.

As we noted in our earlier analysis of the AI threat to Vertical SaaS, the specific threat level is industry agnostic. It comes down to a product’s scale, complexity, and defensibility. Hyper-narrow tools are the nearest-term losers. Products whose core function LLMs naturally subsume — Chegg, Grammarly, Dragon — are next. And hesitant incumbents who don’t adopt AI fast enough will bleed share to AI-native challengers. But vertical technology isn’t any more affected than SaaS as a whole — in many ways, it’s more defensible.

Nicolas Bustamante of Fintool shared a simple framework for evaluating the strength of Vertical Software incumbents:

Is the data proprietary?

Is there regulatory lock-in?

Is the software embedded in the transaction?

He explains, “Zero ‘yes’ answers: high risk. One: medium risk. Two or three: you’re probably fine.” The idea that CRMs, property management systems, or ERPs will fall into a black hole is not something we have seen happen. Workers shifting off document management or project management tools? We’d certainly expect that to occur on a medium-term horizon.

The bears assume that AI will shrink the software market. We think it dramatically expands it, even more so in vertical categories. As we wrote in Vertical AI & the Productivity Paradox, the vertical AI opportunity should be measured not just as labor replacement, but as labor enhancement plus market expansion:

Consider a hypothetical industry where AI can double profit margins by automating labor. Now, imagine the same sector where incremental profits are reinvested into growth. We have the same productivity metric, but the same industry is now >20% larger. Re-investing savings over a five-year window results in a market nearly five times the size with the same productivity. Of course, firms in such a market would likely reinvest only some of their savings into growth, but the net result is a larger and more productive firm (and market).

Foundation model verticalization is real and accelerating. Companies with weak moats and hyper-narrow tooling are exposed. But defensibility is preserved when outcomes require coordination with real-world systems and build the data loops and workflow entrenchment that compound over time. As we wrote in our piece last year on Diffusion of AI across Vertical Markets, we view the primary limiting factor today as not technological, but human capital:

It is these comprehensive end-to-end agentic transformations that are essential to fully revolutionize vertical markets and fulfill the economic potential of LLMs. As such, for founders developing in vertical AI, the hard work must be highly specialized and market-centric. No doubt, technology will continue to advance, but we need vertical builders to see and build the future.

At Euclid, we’re investing in founders who see how AI can transform industries with the lowest digitization and the largest productivity gaps: the complex, gnarly, high-accountability coordination between AI and the real world. This is where the next trillion dollars of enterprise value gets created. And history suggests it won't stop at just one.

Software is dead. Long live software.

Thanks for reading Euclid Insights! Additional sources here.3

Euclid is a VC partnering with Vertical AI founders at inception. If anyone in your network is working on a new startup in this space, we’d love to help. Just drop us a line via DM or in the comments below.

Lakos-Bujas (2026). Equity Thematic Strategy: Software — Historic Crash, Extreme Positioning, Adding Exposure to AI-Resilient Companies. JPMorgan Research.

Ader (2026). Next Week in Software Volume XCI—West Coast Swing. KeyBanc.

Benedict Evans & Ben Thompson (2026). Stratechery Interview: AI and the Future of Software. Stratechery.

Parker Conrad (2026). Twitter/X thread on software cost deflation 1998-2006.

Nihar Bobba (2026). Will Vertical AI Survive? The Last Mile Framework. Twitter/X thread.

Jamin Bill (2025). The System of Record’s Front Door.

Jamin Bill (2026). Software Is Dead...Again...For Real this Time...Maybe.

Nikhil Namburi (2026). Five Tangible SaaS Moats in the AI Era. Twitter/X thread.

Aaron Levie (2026). Every piece of enterprise software has to become a platform play. Twitter/X.

Satya Nadella (2025). BG2 Podcast with Bill Gurley & Brad Gerstner. BG2.

Abraham Thomas (2025). Data and Defensibility. Pivotal.

Lakos-Bujas (2026). Equity Thematic Strategy: Software — Historic Crash, Extreme Positioning, Adding Exposure to AI-Resilient Companies. JPMorgan Research.

Ader (2026). Next Week in Software Volume XCI — West Coast Swing. KeyBanc.

Great article!

Always worth reading because the insights are grounded in first principles "the specific threat is sector agnostic ... (but) not all software is created equal".

I wonder if you'd consider adding a new immutable primitive for software defensibility at scale: not "trust" per se, but the ability to produce evidence that the software behaved as advertised. Valid inputs -> valid workflow -> measurable performance -> validated outputs.

Since I consider AI to be the new Wizard of Oz, I'd like very much to see the man behind the curtain. Without a foundation to think about data-in-data-out, I think even Bustamante's (terrific) three-point framework needs to be qualified to: as long as it can show it's not GIGO.

Thoughts?