The Fundability Trap

“Consensus Comfort” is the Most Expensive Thing You Can Buy

Venture capitalists often describe themselves as being in the business of contrarianism. Living up to that ethos, however, requires fighting against basic human psychology.

As Keynes put it, “worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.” The human evolutionary instinct for self-preservation in consensus is powerful. For venture investors, that cognitive dissonance is especially pervasive in peaks of fear and greed. And — between massive AUM expansions and generational tech paradigm shifts — we are amidst just such a moment today.

The rot of contrarian thinking in venture capital can be boiled down to two distinct concepts that, while occasionally overlapping, are increasingly at odds: fundability vs. investability.

Fundability is a measure of how well a startup fits with current venture consensus. It likely has a repeat founder or a founder from a known entity (Stanford, YC, Ex-Stripe). It operates in a category that is currently “in vogue” (Generative AI, Defense Tech, etc). Investability, on the other hand, is a measure of potential outcome and financial return.

The danger arises when VCs conflate the two — or don’t recognize the difference. We assume that because a deal is fundable (e.g., a central-casting founder, a hot market), it is investible. Conversely, we assume a deal is uninvestible if it is unfundable (e.g., due to an unknown background or an unsexy market). As Kyle Harrison noted in Build What’s Fundable, the risk is that we are building an entire ecosystem that rewards fundability.

How Capital Fosters Consensus

The growing conflation of fundability and investability today is no accident; it is a structural byproduct of market concentration.

The flight of capital into large platform funds that began following the 2021 downturn has continued unabated, making the current venture market likely the most concentrated in history. The downstream impacts are now beginning to surface.

In “We Have Met the Enemy, and He is Us,” we shared a view on how the industry has drifted from its roots as a market for independent thinkers, and how that would lead to a slow calcification into a consensus-driven machine:

Taken to its extreme, venture capital concentration will turn this market into something closer to a planned economy than a capitalistic network of independent competitors. A competitive round with the best firms bidding is, of course, an incredible indicator of potential—unless the bidding is rigged, because firms only bid as a result of other current or past bids. Many have already embraced the monoculture. If a hot YC batch emerges, if a pedigreed repeat founder raises, if a mega-fund plants its flag, everyone rushes in behind them. Demand dictates perceived quality; perceived quality dictates prices. Efficient market!

Since we wrote that piece last Fall, the market has arguably even grown more lopsided: A16Z just raised $15B, equivalent to ~20% of all venture dollars deployed last year. While ~$110B was deployed in total last year–higher than any year on record outside 2021 and 2022–the number of rounds closed (~3,200) was lower than any in the last decade. As a result, the valuation gap between the top “premium perception” startups and the median has grown to 4x.

This new reality has noticeably shifted upstream manager behavior as they seek to benefit from increasingly rich markups. In the process, platform funds have become consensus-building machines, and an increasing share of venture capital is allocated based on fundability rather than investability.

To some investors, optimizing for fundability can look rational. A non-GP partner at a platform fund, for example, might see a consensus deal as “safer”—more likely to produce a better short-term perception of performance, even if downstream returns never materialize. A similar thing can be said for emerging managers. EMs that live or die by conversion from Fund I to II, or II to III–with gaps between fundraises of perhaps two years–face significant pressure to produce markups, brand-name co-investors, and the appearance of momentum at any cost.

This Time It’s Different

Manager pressure to deploy capital into consensus deals is amplified by the current market, both due to the bigger rounds that AUM concentration has produced and the rationalization of “rule-breaking” that a boom cycle like post-LLM AI enables.

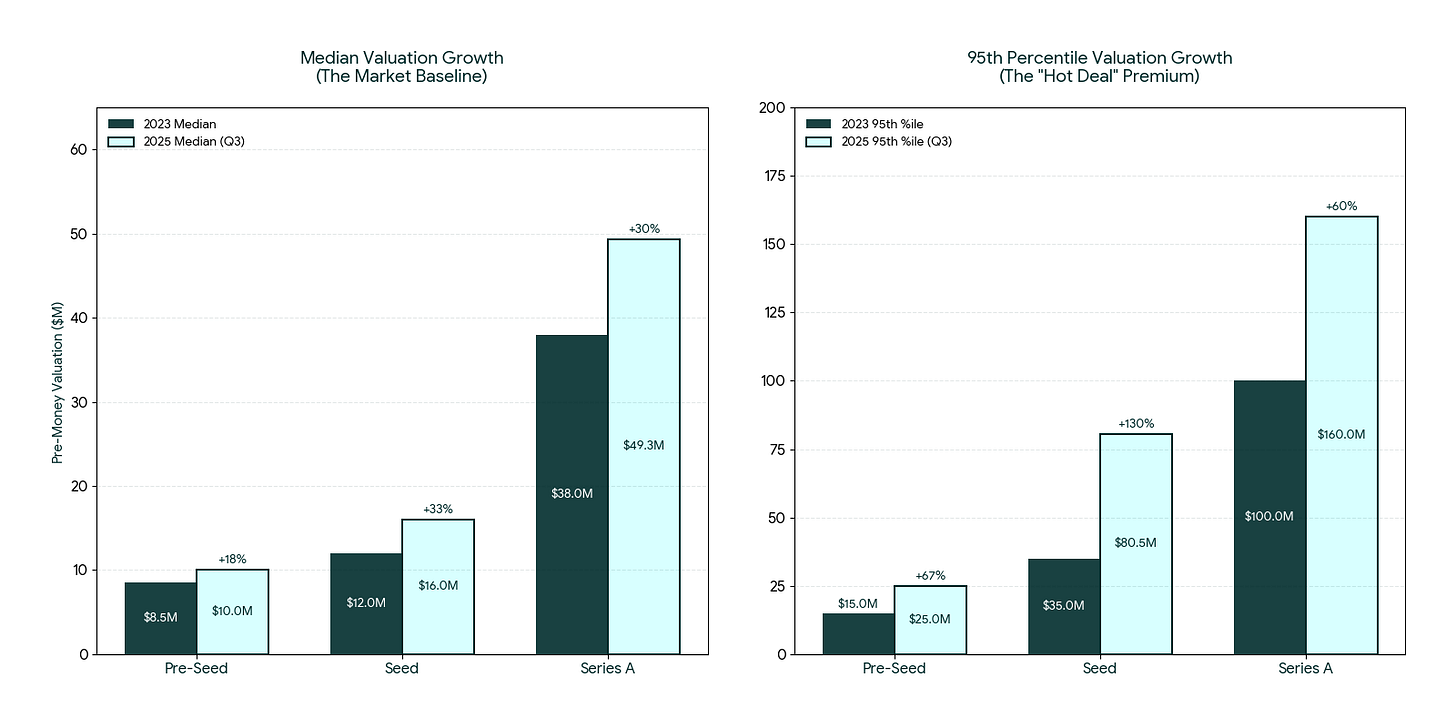

An unavoidable theme in modern early-stage VC markets is larger round sizes and higher valuations. Carta reports 36% growth in median seed pre-money marks over the last year. Particularly stark, however, are recent price spikes for “premium perception” startups. As of late last year, the 95th percentile seed pre-money valuation reached $80M, up 130% from the prior year. The “premium gap” between the median and the top 5% seed has grown to more than 4x.

One popular narrative today is that larger rounds are warranted in this new era of AI. There are various justifications: it grows faster, it’s hyper-competitive, it’s winner-take-all, the first-mover advantage is real, outcomes will be bigger, etc. Some are at least partially true (e.g., growth), while others are purely speculative (e.g., winner-take-all). Most important to the argument for larger seed/pre-seed rounds, however, is the implication that modern AI winners are identifiable earlier. In other words, as the story goes, mega-funds (and their followers) can drive alpha by allocating more capital, sooner, with fewer proof points. Some even argue that outsized first rounds improve companies’ likelihood of success.

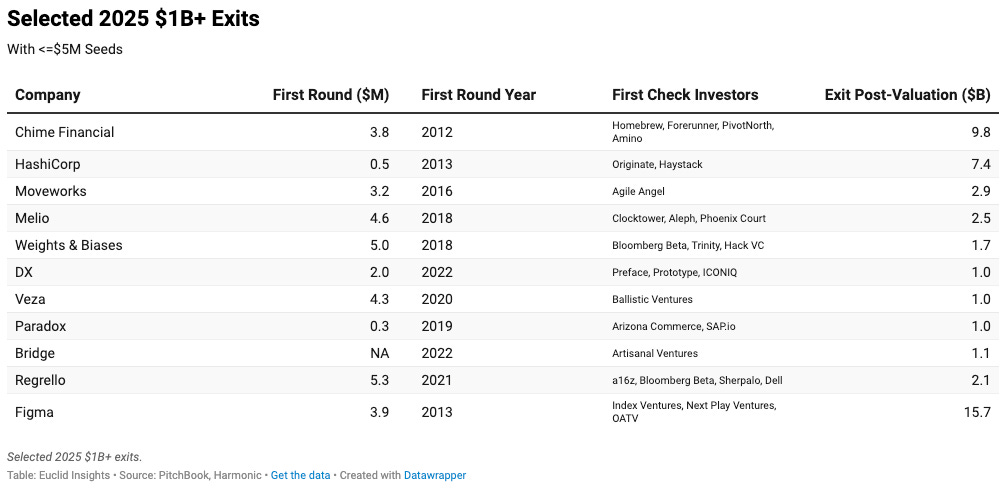

Historical data suggest that this sort of “king-making” logic fails miserably at the earliest stages. We examined $1B+ exits in 2025 and traced them back to their initial rounds. First, the vast majority began with raises in the $500k-5M range (though, of course, there were exceptions, such as Statsig’s $10M round or Neon’s $28M round). Second, while platform funds led some of these smaller rounds (such as Regrello and Figma), they were underrepresented relative to their share of overall AUM. If most future winners were already “legible” at first check–enough to be “king-made”–one would expect to see a far higher share of outsized, platform-led rounds, with such rounds translating into significant outcomes at a greater rate.

Retrospective analysis, however, cannot account for AI, which is introducing dramatic changes to the venture capital world. If the top X% of AI startups are growing significantly faster, funds will inevitably compete by awarding them more capital, earlier. Pre-traction stages, however, are devoid of such signals, AI or otherwise. At first-check, we see no reason to believe the ground truth has changed: that most winners start outside consensus, and often remain there longer than one might expect.

So we must ask the obvious question: are early rounds today growing because opportunities are genuinely bigger and capital reliably confers advantage? Or because large-AUM funds must deploy ever-larger war chests? While the latter is clearly true, credible evidence for the former remains elusive. The obvious virtue of bigger rounds for platform funds is not increasing odds of success, but simply the ability to deploy substantially more capital.

How Consensus Erodes Innovation

The market is responding to this demand for “legible” assets by manufacturing them at scale.

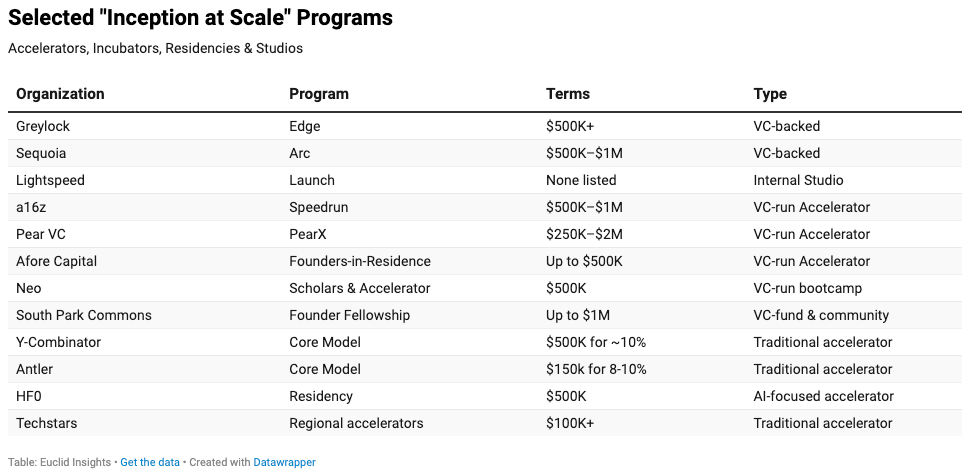

One of the biggest challenges to accelerating venture capital deployment is the limited supply of high-quality assets. Free markets, however, respond naturally to such imbalances. An increase in demand for suitable early-stage assets from downstream funds eventually leads to an increase in formation-stage supply. Indeed, over the past few years, there has been an influx of new “inception at scale” models.

Such programs vary widely, from re-imaginations of community sourcing to internal programs at seed franchises to offshoots of large platform funds. Some of them have been (and will be) successful. The natural incentive of such strategies, however, is to optimize for fundability and hence conversion to seed–especially in a world where inflating seed round sizes provide increasingly juicy markups. While some programs are thoughtful, many tend towards “startup factories,” embracing volume over focus.

In our view, the growth of commoditized early-stage capital pools reduces the value of that capital in signal, brand, and network durability. In other words, as the VC asset class has expanded, the talent pool has diversified, and the number of categories capable of supporting venture-scale outcomes has increased, inception programs should speciate accordingly–greater specialization, creative new funding models, innovative forms of value-add, etc. Instead, we have seen many accelerators become less rational: increasing apertures, cohort sizes, and funds deployed. Typically, they champion the same marketing message: X% of our companies raise seed funding at a $XM+ valuation.

The result is convergence to the most legible, lowest-risk signals from inception. When accelerators attempt to serve everyone, they must default to consensus heuristics—pedigree, age, early traction speed, and alignment with prevailing narratives—because those are the only scalable filters. With little left to differentiate beyond price and branding, and with an increasing number of VCs moving earlier, the talent bar is harder to maintain. Y Combinator’s average founder age has dropped to just a few years out of college; only 17% of the founders in the 2025 batch were over 30, while nearly 60% were under 25. Other newer programs now explicitly target college dropouts, with some even extending to high-schoolers.

The recent explosion in spray-and-pray, inception-at-scale programs, however, feels less like thoughtful innovation designed for durable alpha, and more like a knee-jerk reaction to ballooning supply-side capital and "consensus deal” demand. To quote Kyle Harrison’s essay again:

I reflected on my understanding of why Y Combinator existed in the first place and why, for the first several years, it was so valuable. It represented the best on-ramp for what was, at the time, the opaque world of tech.

But then, you realize that the goal post has shifted. As the tech industry has become dramatically more navigable, YC became much less focused on making the world understandable, revolving, instead, around feeding consensus. “Give the ecosystem what they want.”1

The Fundability Trap

The key to the fundability game, in our view, is not to play it at all. The odds are stacked against most funds, especially emerging managers, and the data suggest a negative correlation between early-stage consensus (high prices) and performance. The investment team at Levels, a data-science-focused venture capital fund-of-funds, analyzed whether high entry prices at the seed stage helped or hurt individual deal returns. Specifically, they examined the probability of a home-run outcome (50x from entry price) for seed / pre-seed investments with valuations below or above $20M. They found that the lower-priced cohort is nearly 4x as likely to produce a 50x+ hit vs. its higher-priced counterparts. An AngelList analysis reached a similar conclusion: although higher-priced rounds were more likely to be marked up, there was no correlation between seed-round valuation and ultimate outlier returns (≥10x).

Multiple studies over the years have demonstrated how the confluence of a market hype cycle and consensus capital can eviscerate returns. One HBS paper examining data from 1965 to 1992 found that venture capital is less efficient in hot markets: capital over-invests in opportunities, too many competitive companies are funded, and the per-dollar return of the strategy declines. Another study from 2017 found that non-consensus investments produce better returns:

We find that consensus entrants are less viable, while non-consensus entrants are more likely to prosper. Non-consensus entrepreneurs who buck the trends are most likely to stay in the market, receive funding, and ultimately go public.

When venture capital focus converges on a consensus asset, market, or theme, it tends to inflate prices, accelerate valuations, and ultimately lead to more frequent and dramatic failures. Regrettably, as we’ve noted before, the incentive persists for VCs to chase popular trends for near-term momentum, even though this tactic demonstrably yields poorer long-term returns.

Despite that, most investors talk about venture as a game to be won solely by “access” to a small set of consensus deals. That framing pushes the industry into a zero-sum, finite game: capital concentrates into a handful of incumbents chasing the most “legible” deals, the opportunity set narrows around the same geographies and themes, and deal activity compresses even as dollar volumes remain large. It’s corrosive to the pursuit of contrarian thinkers and ideas.

If outlier outcomes depend on investing in unconventional or overlooked sectors (especially for non-platform funds), that message seems to be lost, at least with the current VC zeitgeist. According to a survey of 885 VCs (at 681 firms) on the most important component of generating returns, 49% said deal selection, 27% said value-add (a proxy for winning), but only 23% said deal flow. What’s fascinating about this survey is that it runs counter to what the data says (It’s the deal flow, baby!), and while we don’t have the historical data to prove otherwise, the conclusion that 77% of ‘alpha’ is from picking and winning seems to be a strong reflection of a market that has internalized the consensus-is-king message. Dan Gray at Odin covers this dynamic well:

In reality, selection is messy and inconsistent and value-add is questionable, while deal flow is fundamental and often underprioritised — despite research emphasising the importance. As a matter of simple maths, VCs can achieve better investment outcomes with a relatively minor improvement to their pool of opportunities versus a much greater improvement in their picking skill.

Identifying outliers is essential, but doing so by sitting back and picking is an incredibly noisy and difficult skill. Perhaps more importantly, your skill in picking and winning only matters if there are quality options available. This is why venture capital, especially compared to other private equity categories, shows remarkably persistent performance in funds raised by the same GP.2

The irony is that the incumbent firms will argue that “VC doesn’t need more funds, it needs more great companies,” while smaller, conviction-led GPs—often the ones doing the harder work of finding genuine outliers—face a more challenging fundraising environment. Of course, it is in their interests to paint venture as a zero-sum game centered around access to “legible” deals, to compress deal activity and reduce competition while growing dollar volumes. It follows that when megafunds argue that market winners are obvious within two years of founding or must clear some arbitrary growth hurdle, these are logical, if not self-serving, positions for their fund models, as we argued in our essay last Fall:

The concentration of capital in “asset managers” requires a corresponding concentration of capital in companies. You can’t raise your next fund if you can’t deploy the first. Tiger Global’s rise and fall demonstrated the pitfalls of the high-velocity, low-touch investment model. The only other option available—and frankly an easier one, given sourcing and underwriting don’t scale linearly with check size—is to concentrate capital in specific assets. What safer place to do it than in perceived winners in a market you can argue is winner-takes-all?

The underlying truth of venture hasn’t changed: greatness is unpredictable, success is idiosyncratic, and consensus is often a mirage. Chasing fundability over investability has never been a reliable path to outlier outcomes and fund returns. Most importantly, perhaps, is that while ‘consensus comfort’ has many short-term advantages for GPs and EMs alike, in the long-term, it is the most expensive thing you can buy.

Emphasis ours.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092911992300010X