We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us

The Mind-Virus of Big Venture has become a Pandemic

Venture capital has long celebrated itself as the business of contrarianism. The best investors prided themselves on spotting what others missed: the non-consensus founder, market, or product. The venture model was designed to harness outlier outcomes — but it relied on individual conviction, not herd behavior, to find them.

Venture contrarianism was borne out of strategic rationality. As in most investment businesses, there is alpha in epistemic arbitrage. Deep knowledge of a business—its target market, operators most likely to succeed in building it, its underlying technologies, the business models that may or may not work to drive adoption—is a powerful advantage. Only, of course, if that knowledge is asymmetric. The most successful founders (and the VCs that back them) are those who see and believe things that others do not and are ultimately proven right. There isn’t much profit to be had in the conviction that the sun will rise tomorrow. As Peter Thiel observes in Zero to One:

The best entrepreneurs know this: every great business is built around a secret that’s hidden from the outside. A great company is a conspiracy to change the world; when you share your secret, the recipient becomes a fellow conspirator.

Today, that ethos feels increasingly distant. The early-stage financing landscape today is flowing into the same handful of themes, founders, and even funds. Valuations are converging upward as the narrative unfolds of winner-take-all markets, where scale is all that matters. More than ever, investors are outsourcing conviction to a handful of signals: Y-Combinator, elite pedigrees, mega-fund co-signs. More than natural acquirers, incumbent technology platforms have their hands on the rudder—with Microsoft, Amazon, and Meta making unprecedented direct investments and talent bids.

The warning signs are flashing bright red that the venture market has never been more consensus-driven. We believe that the consequences of continued concentration will be catastrophic for venture capital and the broader innovation economy.

The Consensus Crisis in Venture

The capital consolidation that began following the 2021 downturn has continued to accelerate, making the current venture capital market likely the most concentrated in history. According to Pitchbook’s latest data, 41% of all venture capital dollars deployed in the US this year have been allocated to just ten companies. That’s a 75% increase from 2024, and more than double the previous high of the past decade.

We have seen the same dynamics at play on the supply side of venture capital. Last year, more than half of the $71B raised by US VCs in 2024 was secured by just nine firms. In the first half of 2025, just twelve venture firms raised more than 50% of the total capital raised.1 If a16Zz’s next fundraise goes as planned, that single vehicle will match 80% of the total dollars raised in the first half of 2025.

The impact of increasing capital concentration extends beyond a mere change in market texture. It mounts headwinds for the founders and managers who—often due to orthogonal backgrounds and experiences—are less beholden to traditional structures, standards, and patterns of thought. Recognizing that single decision-makers control a significant portion of capital, founders adapt to fit what a mega-fund prefers. In early 2025, we examined the implications in our essay “The Mind-Virus of Big Venture:”

The longer-term concern with capital concentration into a handful of funds is its potential to weaken the link between the innovation ecosystem and free market forces. Just as the “assembly line” approach to venture capital risks producing suboptimal outcomes for EMs, there is an equally harmful impact at the company, or founder, level. Growing capital homogeneity, in our view, leads founders to aggregate around consensus ideas and themes.

It is unavoidable that capital allocation strategies (whether VCs or LPs) are backward-looking in some ways: all investors aspire to identify the repeat patterns of success, even if they aptly recognize that strategies must evolve with the times. As discussed, however, alpha requires being right and contrarian. From our perspective, smaller funds today are mimicking brand-name funds more than ever—the dramatic increase in spin-out funds over the last 18 months is just one indicator that allocator appetite is contributing to this effect.2

But it’s important to note that large platform funds are fundamentally playing a different game. The pursuit of "2% of the biggest number" is consuming venture capital, as the biggest brands in VC become asset managers. Their incentives—from LP profile to target returns—are categorically different, looking less like traditional venture capital and more like multi-product private equity. Our view is that imitating the tactics of a player in a different sport is not a strategy for success—in the case of the early-stage VC managers, it’s more likely a path to obsolescence.

Venture Capital Arrogance

Josh Koppleman introduced the concept of the Venture “Arrogance Score” in a recent interview. We found it to be a convincing and succinct way to visualize the increasingly challenging math of mega-funds. The idea is to analyze the percentage of annual VC-backed exit value that a venture fund would need to achieve to beat a gross cash-on-cash return hurdle. You can find the explanation of the math behind the score here. For simplicity, we’ve assumed a target 3x gross return, a 3-year interval between new funds, and a 15% ownership stake at exit. We highlighted three examples: the average top 5 and top 9 largest funds raised in 2024, in addition to the rumored $20B A16Z fund. We calculate scores using today’s annual set value ($180B) and two hypothetical future annualized exit values ($300B and $500B).

As Josh points out in his interview, a figure greater than 10% would be considered exceptional. The requisite scores on the above funds would require Herculean assumptions regarding fund performance and the total exit environment. The above rumored A16Z $20B fund, for example, registers an astronomical arrogance score (even at a generous 3-year deployment cycle). Given that their last announced fundraise was in early 2024, one could argue the score should be twice as high (requiring more than 100% of proceeds possible from projected exits). And remember, these figures are calibrated around a 3x gross (~2x net) fund, anemic by VC performance targets.

Some platform funds might argue that these figures represent an aggregated amount across diverse strategies and products. New themes, such as cryptocurrency and defense technology, are emerging venture capital categories in rapidly growing “new” markets. New strategies—such as M&A roll-ups and/or tech-enabled services—open up non-tech portions of the economy for value capture and fund returns. AI acceleration itself, moreover, has enough transformative potential to suggest a re-thinking of macroeconomic assumptions.

We agree with some of these points. But they do little to help us overcome the built-in “suspension of disbelief” that these arrogance scores require. While secondary VC products are on the rise, they are just that: a minority of AUM by a wide margin. Our challenge with AI-acceleration arguments has less to do with postulates and more to do with conclusions drawn. As AI captures more of the economy, as software has been doing for years—why should that lead to more capital concentration?

AI acceleration should see more markets to chase and more diverse opportunities for value creation, even if they continue to build on an infrastructural oligopoly. Growing market depth and breadth should foster increased investment fragmentation, rather than increasing the concentration of capital. This has been the trend over the past 30+ years and multiple technology deployment cycles.

The results show the opposite occurring. In 2023, approximately one-third of global AI funding went to rounds exceeding $1 billion. In 2024, that figure was half; so far in 2025, nearly two-thirds of funding has been invested in rounds exceeding $1 billion. These AUM increases are so significant that the justification for their ability to deploy them while maintaining market-beating returns requires suspending disbelief.

Returns aside, there is a more obvious and immediate effect: the concentration of capital in “asset managers” requires a corresponding concentration of capital in companies. You can’t raise your next fund if you can’t deploy the first. Tiger Global’s rise and fall demonstrated the pitfalls of the high-velocity, low-touch investment model. The only other option available—and frankly an easier one, given sourcing and underwriting don’t scale linearly with check size—is to concentrate capital in specific assets. What safer place to do it than in perceived winners in a market you can argue is winner-takes-all?

The Age of “Power-Law” Consensus

Bill Gurley observed in a recent podcast interview that the “power law”—once a truism used to underscore the importance of a contrarian, high-conviction approach to venture—has become corrupted, repurposed into consensus-validating dogma. The argument runs that AI will generate a handful of trillion-dollar outcomes. Hence, VCs should go all-in on a narrow set of companies they believe can be one of these winners, achieving unprecedented scale that will justify high entry prices. In his piece on the growing crisis in the seed market, our friend Rob Go of NextView concisely describes this view:

But today, the power law is consensus thinking. The highly skewed distribution of outcomes is clearly evident in early-stage investing, but also in the broader market. On top of this, the market now believes that the level of disparity between the super-outliers and the non-outliers is much, much greater than previously imagined. The best companies aren’t just 10X more valuable, they are 1000X more valuable.

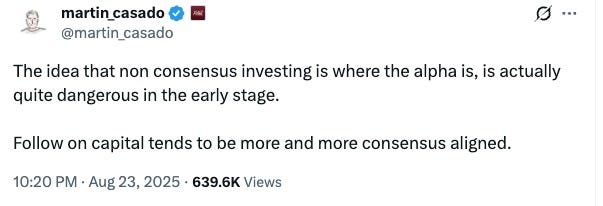

There was also an interesting, relevant Twitter exchange a few weeks ago after a16z GP Martin Casado suggested that there is little to no alpha in non-consensus early-stage investing:

Martin followed up with a longer explanation in an interview with Newcomer:

Unpacking the point with him, what he’s really trying to assert is that early stage rounds are part of an efficient market. He’s saying that startups that go on to succeed will have tended to raise at higher prices in those early rounds than companies that fail.3

There’s a lot to unpack here, but the most critical is the erosion of differentiation this worldview suggests. Like a good in any market, ceteris paribus, price reflects perceived value. The aspiration of the efficient market is that many players with diverse views, resources, and means compete to drive discovery of a price aligned with intrinsic value. That “crowd-sourced” benefit falls away when there are too few buyers, or buyers who fail to decision independently. Tulip bulbs in 1635 Amsterdam didn’t turn out to have much more value than a common flower, but with hordes of unthinking investors chasing the same commodity, prices skyrocketed.

Taken to its extreme, venture capital concentration will turn this market into something closer to a planned economy than a capitalistic network of independent competitors. A competitive round with the best firms bidding is, of course, an incredible indicator of potential—unless the bidding is rigged, because firms only bid as a result of other current or past bids. Many have already embraced the monoculture. If a hot YC batch emerges, if a pedigreed repeat founder raises, if a mega-fund plants its flag, everyone rushes in behind them. Demand dictates perceived quality; perceived quality dictates prices. Efficient market!

From the perspective of a top capital aggregator, this perspective is, of course, a rational one to take. The asset manager theory of today’s power-law consensus VC model requires believing that owning the best assets is all that matters. Returning to Rob Go’s essay, he observes:

So, if you are a scaled player in a market where the power law is the consensus view, there is really only one rational strategy. And that’s to be a price-insensitive index of any company that has the potential to be a super-outlier and then concentrate capital from there.

Later in the interview, Martin from a16z effectively confirms this view:

What matters in venture capital these days, he said, “it’s access, it’s winning , and it’s having the right fund structure to be able to enter the casino.”

A scaled venture fund and its backers may argue that the AI platform shift will be different, allowing mega-funds to generate a different return profile than historically possible with such concentration. We previously evaluated the argument and found that it lacks merit. “This time it will be different” is the last bastion of both poor logic and bold showmanship. In our view, there is more substantial evidence that the opposite is true, and that hyper-scaling venture funds rarely works. We analyzed the top 20 “big brand” firms after 2007-8, and found that 55% “went through a meaningful restructuring event post-GFC: strategy pivots, team shake-ups, rebrands, and/or wholesale shutdowns.

In truth, there is little evidence that venture capital is—or ever truly was—an efficient market. Neil Mehta of Greenoaks, for example, suggested that their own data over the last 13 years indicates little difference in pricing at the Series B between the eventual winners and losers in a category. Neil’s internal analysis suggests that “there are exceptions here and there, but by and large, very few people could actually tell the difference between the two.”

Of course, in a world where only a handful of investments generate most of the returns, it follows that securing an investment in an outlier outcome is far more critical than marginal differences in entry valuation. As Paul Graham observes:

Valuation matters far, far less than the decision of whether to invest or not. The spread between bargain and outrageous startup valuations can't be more than 5x, in a world where the best investments can return 1,000x.

However, that is a different argument from Martin’s hypothesis, which suggests that the entry price should be strongly correlated with outcome size and returns. An analysis by AngelList of thousands of seed-stage investments found that there’s a “5x spread between typical top and bottom quintile seed deals and no apparent difference in those deals’ performance.” In evaluating the growth stage of the market (where arguably market efficiency should be even higher), an analysis of growth-stage deals by Cambridge Associates found “limited correlation between entry pricing and investment outcomes.”

In other words, deals done at higher multiples did not systematically outperform or underperform. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Cambridge’s analysis found that post-investment growth rate was the strongest indicator of performance. If only investors could predict that with any accuracy!

We admit, it’s very much possible that company-level capital aggregation may have a different effect—in other words, that pricing is more indicative when it’s driven less by valuation and more by pure dollars in. Significant funds declaring winners early in a category’s development may provide an unfair capital advantage. But that certainly would not be in line with the market efficiency hypothesis suggested above, nor an example of free market forces at work. It’s even harder to argue that such investments could reflect “crowdsourced” intrinsic value vs. pure perception. And as many SoftBank and Tiger-backed companies can attest, often the only thing companies maximizing dollars raised or valuations achieved prove is how quickly a startup can spend the money it raises.

The Consensus-Driven Early-Stage Squeeze

The impact of the “Consensus Power-Law” is an increasingly concentrated venture capital market, even at the earliest stages. Fewer investments, larger deal sizes, and extreme valuations align around box-checking assets. The total number of venture capital rounds raised in 2025 is on pace to be the lowest in nearly a decade, while the average capital raised per company is nearly at the 2021 highs.

At Euclid, we are, of course, most interested in what is happening at the earliest stages. Several datapoints illustrate that the same dynamics are flowing upstream. According to Carta’s analysis, the total number of seed rounds has decreased by nearly 50% since 2021, while valuations have increased by 30% over the same period. Looking across all first-time financings, 2025’s deal count is on pace with 2015 but with >2x the capital raised.

Ongoing consolidation is particularly evident when examining the share of VC deals under $5 million over the past decade. In 2015, sub-$5 million rounds represented roughly two-thirds of all deals. In 2019, they were down to ~55%. So far in 2025, that figure is down to one-third of all investments.

Series A is no different: the total number of rounds has decreased by 60% since 2021, while valuations are roughly flat from their peak. However, upon examining the valuation numbers, a significant bifurcation emerges between the haves and have-nots. The analysis below displays the valuations over the past twelve months for Seed and Series A companies at various percentiles.

The valuations at the top ranges are certainly jaw-dropping, but we find the delta in prices to be more illustrative. The delta between even a top 5% and a top 1% deal is well over 100% in both scenarios. In a consensus market, where investors compete for a perceived scarce number of high-quality assets, one would expect a growing spread of prices, with that spread being higher at later stages, when more data and information are available. Both dynamics are true above.

Recently, Beezer Clarkson of Sapphire Partners published an analysis of over 2,000 early-stage priced rounds since 2022. The overall takeaways confirm our own: round sizes have inflated, valuations have escalated, and the early-stage market has bifurcated into “haves” and “have-nots.” Interestingly, the participation of mega-funds in seed investments has remained relatively constant at 25-30% over the past three years. While they are certainly more active in the jumbo-seed market ($>6M seeds), the overall shift in the seed market towards fewer, but larger rounds at higher prices is driven overwhelmingly by the non-mega fund portion of the market.

The Negative Impact of Conformity Bias

The gravity of mega-funds has had adverse effects that extend beyond just fund performance, spreading poor practices throughout the entire early-stage ecosystem. An extremely right-skewed version of the “power-law” becomes the underwriting consensus for funds of all shapes and sizes. While we agree that venture market returns are highly skewed, it goes without saying that no early-stage manager should need a >$1T, >$100B, or even >$50B outcome to deliver a >5x fund.

We do concede that allocator preferences have created strong incentives for smaller funds to emulate the behavior of larger funds. Co-investing alongside brand-name funds is easy to market and fundraise from. However, as we highlighted in our previous Mind-Virus essay, there are real dangers for smaller and emerging managers who fall into this consensus-chasing paradigm:

There is no doubt that the quality of funds marking up a portfolio can be a leading indicator of success. All managers should be cognizant of “next buyer” psychology. Deducing early-stage investment priorities from downstream brand-fund preferences, however, is like stock picking based on last year’s S&P 500 performance.

It’s worth noting that if the Consensus Power-Law market is producing better follow-on rates, it is not evident in the early data. Even as the seed market has become more consolidated, graduation rates remain significantly depressed compared to prior years. The percentage of startups that raised a seed in 2024 that have raised an A lags well behind the pre-COVID and post-COVID cohorts.

Of course, the deeper problem with consensus is not simply follow-on rates, valuation inflation, or even deal scarcity. It is the thought-chilling conformity that undermines the fundamental purpose of venture capital: independently-thinking GPs with diverse strategies taking risks alongside founders, competing in a vibrant market to help build category-defining businesses.

We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us

The nature of information asymmetry in venture capital has evolved in tandem with a 50-fold increase in AUM over the past 30+ years. In that more rarefied environment, access was the advantage. As a VC, your proximity to a handful of key companies and operators—in addition, of course, to prices you were willing to pay and your ability to back the right companies—dictated success.

This information asymmetry heavily favored incumbents. In the 1990s, only 25 venture firms had at least one of the top ten annual deals, and five captured more than 8% of the total top deals during that period. In the following decade, a prolific one for new firm launches, 70 firms were amongst the top 10 deals, and no single firm captured more than 8%.4

While the vast majority of the best-known brands in venture operate as multistage generalists, it’s easy to forget how old they mostly are. BVP and Greylock (two of the best of all time) were founded in the 1960s. Sequoia, Kleiner Perkins, Mayfield, NEA, CRV, and Menlo all launched in the 1970s, with Accel a few years later. Benchmark and Insight were both founded in 1995, and by 2005, Lightspeed, Index, Redpoint, Founders Fund, USV, Emergence, First Round, and Y Combinator had also been established.

Most of the top-performing venture firms founded after 2005 began with strategies tailored to their era. They built competitive differentiation by stage (First Round Capital, Felicis, Founder Collective), geography (Foundry Group), thematic focus (Emergence, USV, Ribbit), or a combination thereof (IA Ventures, Amplify). Many storied firms of the prior generation did not keep up with the times and faded away.

What is true in the vertical markets we invest in at Euclid is equally valid in venture capital broadly: the best way to beat your competition is by out-specializing them. We have always enjoyed this piece of advice from our friend Jake Saper at Emergence (as relayed by Rick Zullo at Equal):

[Jake and I] talked about the power law dynamics of venture and why being top 5 wasn’t enough, ultimately it was about being #1 – as [Jake] called it “being king or queen of your island.

For Emergence, their island in early-stage B2B SaaS was actually relatively small when they started over 20 years ago. Back then, SaaS was <2% of overall software budgets; today, it’s well over 50% and clearly a sizable domain. For Euclid, of course, our island is also intentionally small today at the inception stage of Vertical AI.

In today’s venture ecosystem, it is arguably easier than ever to identify and connect with promising entrepreneurs and startups, especially the earlier you go. This will only be amplified by the growing AI and data tools available to firms of all sizes and shapes. However, at the same time, founder mindshare has become more fragmented and competitive to win than ever before. Access has become than just seeing, it’s also brand and the right to win.

It goes without saying that it becomes nearly impossible to own an island when replicating a brand-name fund’s thesis (or even strategy). Finding an island that you can own is key, as over time, a successful island becomes a durable brand. If the future of access is brand, one thing is clear to us: differentiated, defensible strategies for building mindshare with great founders at scale will define the next generation of early-stage manager success.

You may recognize the title of this essay from the influential Kauffman Foundation essay from 2012, but it actually originated in Pogo, the comic strip by American cartoonist Walt Kelly. The phrase traces back to naval commander Oliver Hazard Perry’s famous dispatch during the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812: “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” Kelly reworked the iconic line for an anti-pollution poster in 1970 and again in a 1971 Earth Day strip. Since then, it has endured as a potent reminder that the greatest threats we face rarely come from an external “enemy” — they so often come from ourselves.

Thanks for reading Euclid Insights! Euclid is a VC partnering with Vertical AI founders at inception. If anyone in your network is working on an idea in the space, we’d love to be helpful. Just drop us a line via DM or in the comments below.

Pitchbook (2025). 12 firms collected over 50% of all venture cash in the first half of 2025.

Per a 2025 study, 36% of recently surveyed LPs saw an increase in spinout funds, while just 3% saw a decrease. Coller Capital (2025). Global Private Capital Barometer 42nd Edition.

Hajer (2015). Venture Capital Disrupts Itself: Breaking the Concentration Curse. Cambridge Associates Research Note.