Vertical AI & the Productivity Paradox

Labor rules everything around me

Abstract

+ We discuss the "AI will kill jobs" narrative & technology's historical impact on productivity across generations

+ Where and how Vertical AI can impact labor productivity & produce large venture outcomes

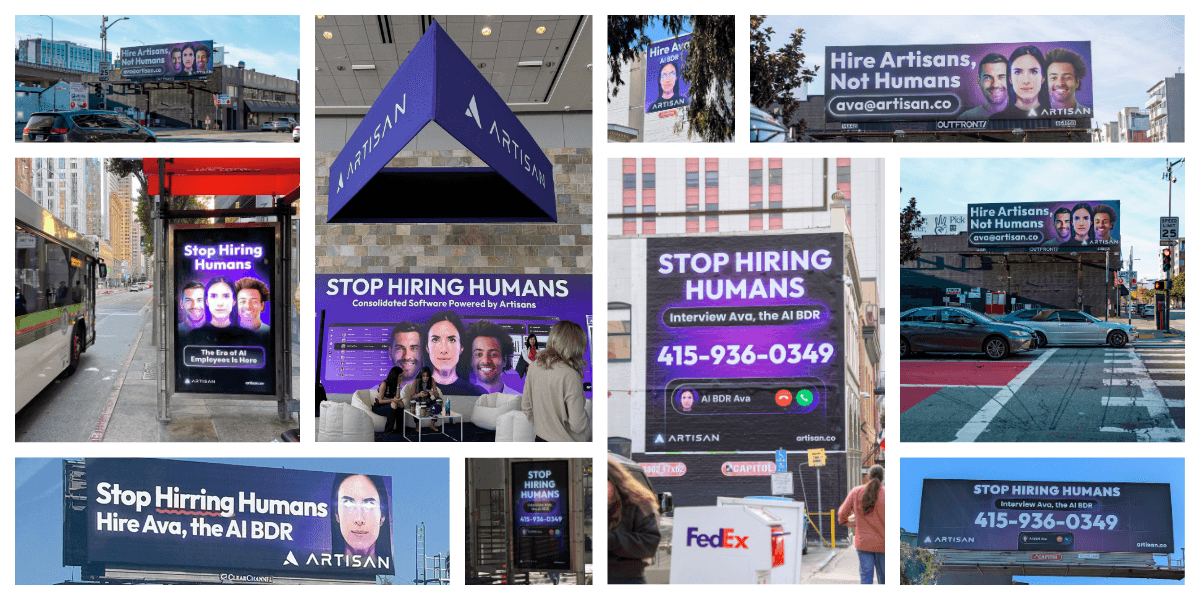

+ Why messaging and perception matters for AI If you’ve been around San Francisco over the past few months, you’ve probably seen these ads on bus stops and billboards.

The campaign went viral across social media, and the company eventually published a blog defending the billboards:

We didn’t expect people to get so mad. The goal of the campaign was always to rage bait, but we never expected the level of backlash we ended up seeing… Luckily, the people who were mad aren’t our target audience. We target tech companies, and the vast majority of people who work at and run tech companies loved the campaign.

We don’t mean to pick on one startup, as many have shared similar sentiments. Consider the comments by Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei last week in an interview with Axios: “AI could wipe out half of all entry-level white-collar jobs..AI companies and government need to stop "sugar-coating" what's coming: the possible mass elimination of jobs across technology, finance, law, consulting and other white-collar professions, especially entry-level gigs.”1

Vista Equity CEO Robert F. Smith shared a similar view, telling 60% of the 5,500 attendees at the SuperReturn conference last week that they will be out of work next year due to AI.2 Curiously, some venture investors (including Marc Andreessen) predict that venture capital might be one of the few professions relatively unscathed by AI.3 We’re sure the irony isn’t lost on our readers.

Technology’s Impact on Jobs

It’s interesting to reflect on AI replacing human jobs and why so many startups and their backers seem to be pushing that messaging. With all these fear-inducing public statements, it might be unsurprising to learn that AI has a public perception problem. In a recent survey, only 13% of respondents believe artificial intelligence will do more good than harm on a societal level.

The perception of AI’s impact (disseminated mainly by megacap tech, startups, and their backers) is perfectly aligned with, and in direct conflict with, all known historical precedent. Every meaningful labor-reducing, productivity-enhancing technology in history has led to fears of massive job losses, yes. But what has invariably followed is increased productivity, lower prices, and entirely new products and services. Since 2000, for example, labor productivity has increased by 89% while the labor force has increased by 24%. This is not to say that the internet is necessarily responsible for these gains or that there aren’t concerns around specific other trends (e.g., wage growth), but rather to make the point that technology paradigm shifts have historically yielded long-term good.

Let’s consider personal computers and spreadsheets as an example. They first emerged in the late 70s, but were mainstream by the late 1980s. A research report from Morgan Stanley describes the impact:

"As adoption of this technology grew rapidly throughout the 1980s, especially after the introduction of Microsoft Excel in 1987, we saw a reduction in the number of Americans working as bookkeepers and accounting/auditing clerks (from ~2 million in 1987 to just above 1.5 million by 2000) — but we also saw a significant increase in Americans employed as accountants/auditors (rising from ~1.3 million in 1987 to ~1.5 million in 2000) and management analysts & financial managers (from ~0.6 million in 1987 to ~1.5 million in 2000)"

The ATM is another illuminating case study. While many worried that the rapid installation of ATMs would decrease the number of bank teller jobs, they had the opposite effect:

The average bank branch in an urban area required about 21 tellers. That was cut because of the ATM machine to about 13 tellers. But that meant it was cheaper to operate a branch. And when it became cheaper to do so, demand for branch offices increased. And as a result, demand for bank tellers increased.4

It is important to note that these numbers show the total number of people employed. That would provide little solace to individuals who might lose their jobs without the ability to retrain into a related profession or be stuck outside the workforce while demand rebounds.

Earlier this year, Goldman Sachs predicted AI would impact 300 million jobs worldwide, activating substantial dislocation in the labor market. The World Economic Forum’s Future Jobs Report analysis suggested the transformation of the labor market would create 170 million jobs by 2030. However, that would be partially offset by the prospective loss of 78 million jobs over the same time frame.

For a stark example, consider LLMs' impact on specific categories of digital freelancers. A study from Harvard Business Review calculated a 21% decrease in automation-prone jobs (writing, app, and web development) across online gig worker marketplaces.4 Undoubtedly, there will be a meaningful reduction in specific automatable jobs over the coming years. Employers, universities, and the public sector will need to invest in upskilling, reskilling, and other initiatives to soften the impact on workforces. We’ll come back to this later.

Technology & Labor Productivity

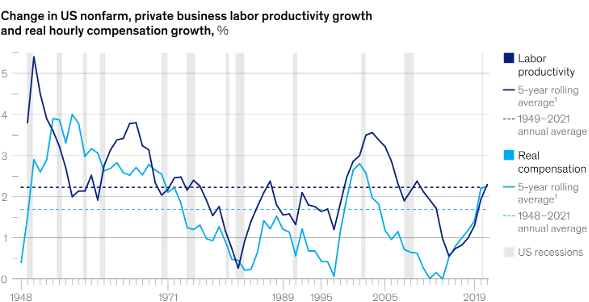

Despite the rapid advancement of technology over the past two decades, one interesting artifact is that increased labor productivity gains from the internet era have not been sustained, running well below its long-term average of 2.2%. While it’s clear there was undoubtedly a meaningful hangover from the GFC, the impact is still stark.

This chart shows five-year rolling averages of labor productivity and real wage growth in the post-war United States.5 You may also notice that productivity and wages move in relative sync. If we isolate the last fifteen years before COVID, labor productivity grew at the slowest rate since the end of World War II. The decade prior, however, had the highest labor productivity growth in modern history.

When digging further into the lagging productivity over the last few decades, there is a clear bifurcation between high- and low-productivity industries. Large service-led sectors, such as construction, food services, transportation, and healthcare, are among the largest domestic employers (37% of total hours worked), while they only contribute 24% of economic output. These laggard industries have seen a productivity CAGR below 0.5% since 2005, with construction even decreasing productivity over that period. Unfortunately, these sectors have also accounted for more than two-thirds of all employment growth since 2005, dragging down overall economic performance.

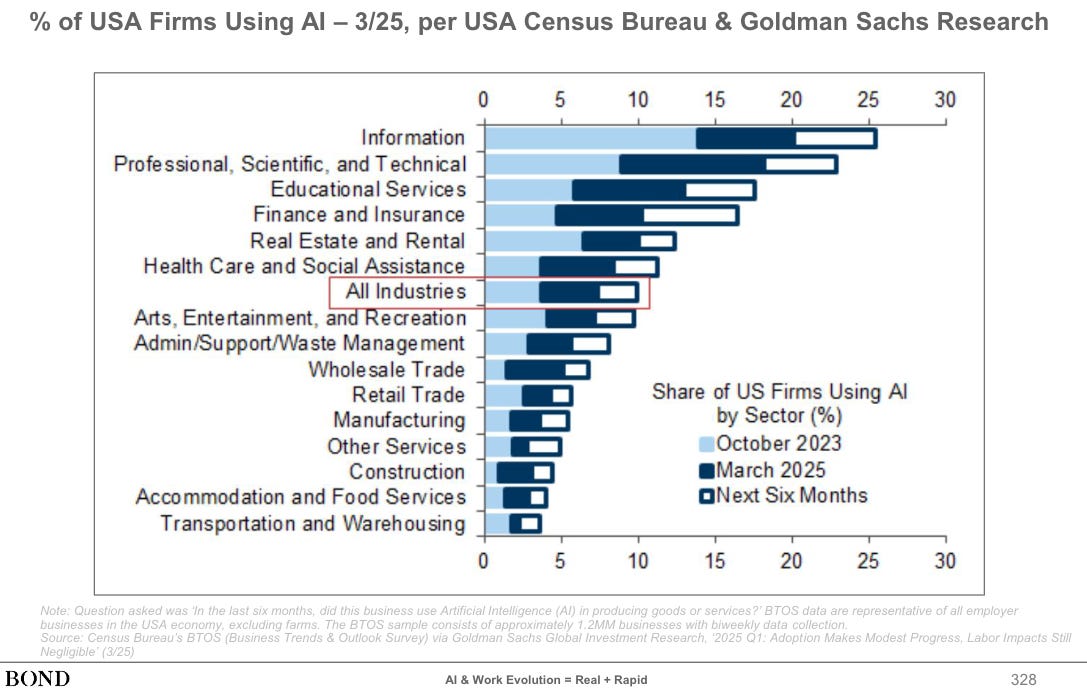

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these labor-intensive verticals are also extreme laggards regarding technology adoption. In fact, a McKinsey study found a 70% correlation between digital adoption and a sector’s productivity growth. There is no credible path for boosted economic productivity without a digital transformation of these markets. Construction and healthcare, specifically, are within the top six sectors by GDP contribution yet rank lowest on the digitization index. Interestingly, early surveys indicate the healthcare sector is above the median for AI adoption, while other laggard sectors remain well below.6

Why does all this matter? Returning the US economy to historical productivity growth rates would add $1T to the US GDP yearly. In other words, productivity gains alone could boost GDP by 3-4%, and technology will need to play a critical role.

Vertical AI & the Productivity Paradox

In our view, an operative assumption around Vertical AI is that TAMs will be much larger than traditional software markets as they subsume labor and services. In their primer on Vertical AI, the team at Besssmer suggests the category’s “market capitalization will be at least 10x the size of legacy Vertical SaaS as Vertical AI takes on the services economy and unleashes new business models uniquely capable of serving this category.”

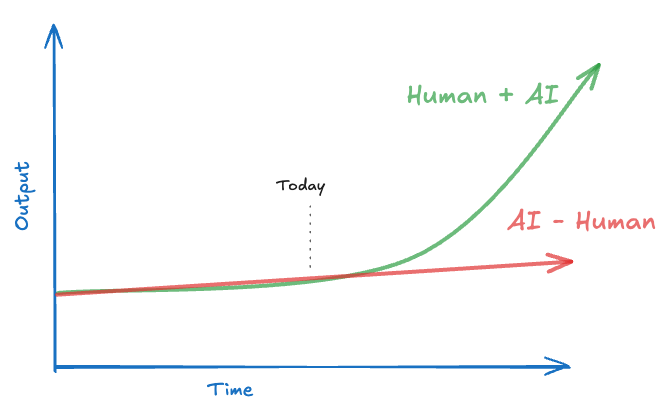

To date, however, much of the narrative around the value of AI has centered around direct labor replacement, given the immediate profit potential for buyers. Our growing belief is that AI's greater impact (and the larger market opportunity) will be its ability to enhance workforce productivity. These are two sides of the same coin, but we think the distinction matters, especially in terms of the long-term opportunity size.

Consider a hypothetical industry where AI can double profit margins by automating labor. Now, imagine the same sector where incremental profits are reinvested into growth. We have the same productivity metric, but the same industry is now >20% larger. Re-investing savings over a five-year window results in a market nearly five times the size with the same productivity. Of course, firms in such a market would likely reinvest only some of their savings into growth, but the net result is a larger and more productive firm (and market).

We believe the Vertical AI opportunity should be measured similarly: factoring in reinvestment in addition to replacement. Compared to improved productivity alone, the most significant outcomes will be those that increase productivity AND market size.

This is especially important when considering the types of work AI can and will automate shortly. As our friends at Tidemark describe, native AI applications are best suited for two main use cases:

Administrative work (scheduling, recording, invoicing, etc.): Back-office work is time-consuming, inefficient, and likely not done well.

Work not done: Work that should be done but isn’t because of time, resources, etc. Bidding on more work, answering calls after hours, etc. This is the biggest known unknown but also the most compelling opportunity.

While freeing up administrative work may require less headcount, tackling the work that has yet to be done will arguably have the opposite effect. In other words, it will enable businesses to take on more projects, customers, patients, etc., and grow their revenue. In other words, they can focus on delivering more of their core services; more business will likely require more headcount, and so forth. In steady-state and even with continued automation of back-office work, the more productive firms will combine enhanced labor productivity with AI to grow and outperform.

What Comes Next

Of course, we do not expect such a seamless labor transition across all verticals, and major disruptions will certainly happen. In an annual letter from 2015, Warren Buffett examined several historical examples of technology adoption, productivity gains, and the impact on labor. In 1900, roughly 11 million Americans, or 40% of the workforce, worked on farms. Through the introduction of tractors, irrigation, and other innovations, today, approximately 3 million Americans (2% of the workforce) work on farms, while we produce roughly ~6x the output. Buffett describes the impact:

It’s easy to look back over the 115-year span and realize how extraordinarily beneficial agricultural innovations have been – not just for farmers but, more broadly, for our entire society. We would not have anything close to the America we now know had we stifled those improvements in productivity. On a day-to-day basis, however, talk of the “greater good” must have rung hollow to farm hands who lost their jobs to machines that performed routine tasks far more efficiently than humans ever could.

The answer to such disruptions is not restraining or restricting innovations that improve productivity. Americans would be far less prosperous if 40% of the workforce (or 11M people) were still employed in farming. We would argue that it does not excuse flippantly discussing job losses or ignoring the societal consequences for individuals whose talents and skills are no longer valued because of market forces. Humanity will require time, empathy, and help to adapt to inevitable changes fostered by technologies like AI.

The perception challenges of AI may become adoption challenges, harming not only startups and their backers but also productivity gains and ultimate societal prosperity. As Buffett concludes in his letter, “the price of achieving ever-increasing prosperity for the great majority of Americans should not be penury for the unfortunate.” We think such advice remains a timely reminder for the ecosystem as a whole.

https://www.axios.com/2025/05/28/ai-jobs-white-collar-unemployment-anthropic

https://www.entrepreneur.com/business-news/vista-ceo-tells-superreturn-attendees-ai-will-take-your-job/492825

https://fortune.com/article/mark-andreessen-venture-capitalism-ai-automation-a16z/

https://www.aei.org/economics/what-atms-bank-tellers-rise-robots-and-jobs/

https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/rekindling-us-productivity-for-a-new-era#/

https://www.bondcap.com/report/tai/#view/335

Great article! Makes me want to dig in further on historical labor productivity gains in general. A few questions and comments:

1. Labor productivity - you mention in the first paragraph that labor productivity has grown 89% since 2000 (in the US?). But then in the subsequent paragraph it chart and CAGR numbers make it seem like it should be closer to 60? Maybe I am misreading. Also worth noting that the labor force participation rate has decreased about 5% over the last 20-25 years, which would boost productivity at equal outputs. It does seem clear that the initial onset of PC’s, internet, software created better gains than the resulting SaaS boom… until now?

2. The nice anecdotes about PC’s and spreadsheets make me think of what the existing analog would be for tech. Maybe that overall companies will shed workers, but more will transition to being solopreneurs, micro-funded start-ups, small businesses in general and produce in aggregate more output. Would you need to see an increase in the labor force participation rate for this to be a meaningful change, or at least a nominal increase in tech employment?

3. Sundar stated that Google measured a 10% boost in productivity due to AI. What is your take on that? It seems significant that one of the AI innovators, who seems to have a good systematic way of measuring output, is achieving *only* 10% gains, especially when you constantly hear the 30% number among tech people. Perhaps AI currently delivers much better gains to the early part of the product development cycle vs. further along with mature products and teams in mature markets.

Finally what is your take on Andreesen's comment that AI won't come for VC's.. is it harder or easier out there for a VC right now? If you don't need capital to start a company and create value, how does it affect VC?