A Guide to Disrupting Incumbents

Part I: Commoditizing Your Complements in the Era of Vertical AI

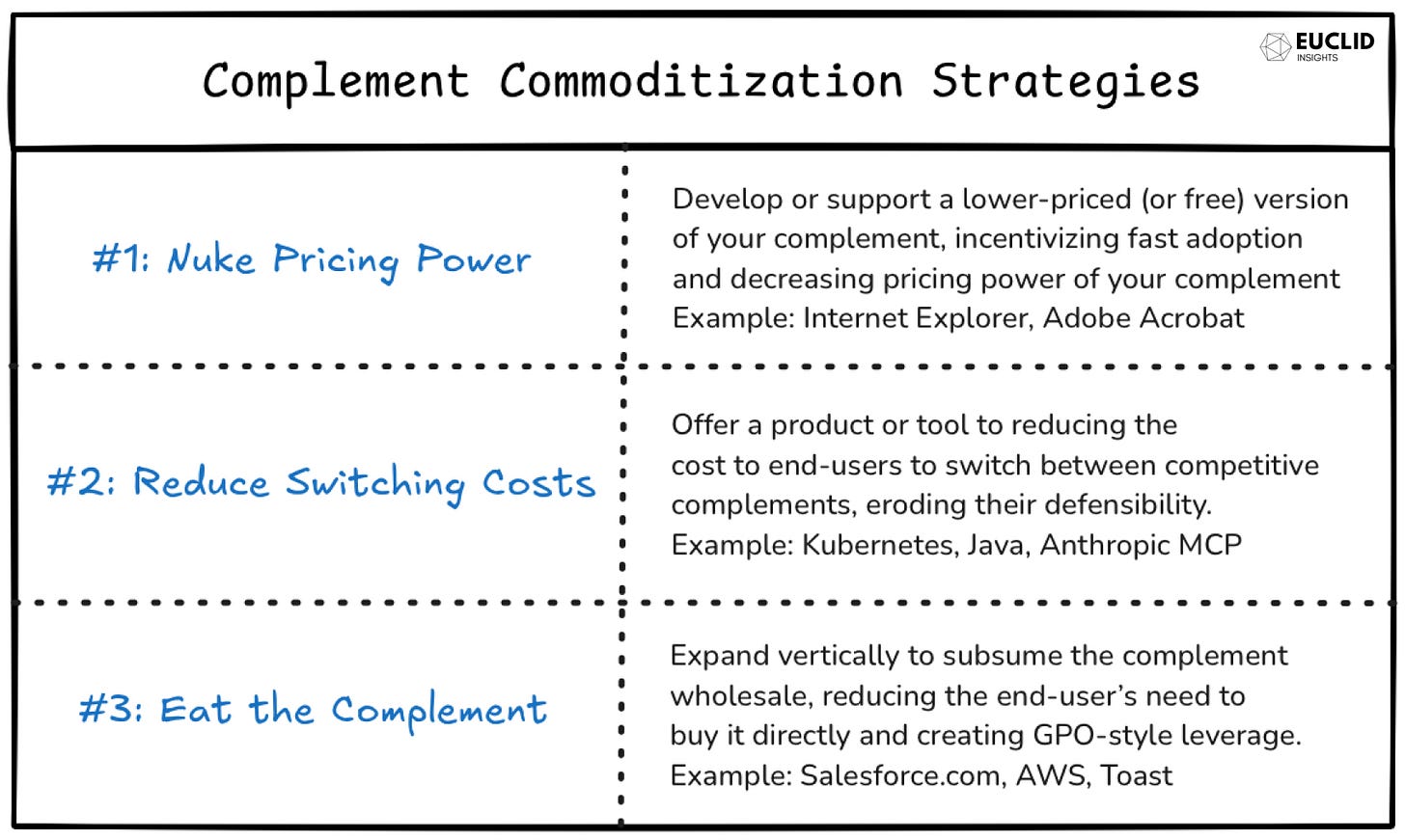

TLDR: In this essay, the Euclid team unpacks a key strategy startups can use to disrupt incumbents: complement commoditization. We cover the 3 main methods and their growing relevancy in the age of Vertical AI.

1. Three strategies to shift value: Weaken incumbents' market positions by reducing complement prices, switching costs, or direct demand.

2. Avoid backfire risks: Don't commoditize complements key to your own product's lock-in or assume incumbents will not retaliate.

3. Position for value capture: Ensure your product strategically captures the value flow once complements become commoditized.

Introduction

In 1998, economics professors Hal Varian and Carl Shapiro published Information Rules,1 a magnum opus on the economics of software. Their re-imagination of corporate strategy for the information age set the groundwork for a range of now-ubiquitous concepts like lock-in and network effects. While the work remains as valid as ever, the ongoing evolution of AI—in our view—is changing the game. In this two-part essay, we will dive into one Information Rule that vertical AI businesses going up against powerful market leaders would do well to remember: commoditizing complements.

Today’s essay will introduce the variants of the strategy, case studies of success and failure on each, and our view on heightened applicability in today’s markets, thanks to the rise of both vertical software and LLM-powered products. If you’re a founder or executive aiming to gain leverage and capture market share in the face of an entrenched software ecosystem, today’s essay is for you.

An Intro to Commoditizing Complements

Like many brilliant frameworks in software strategy, complement commoditization was first popularized by Joel Spolsky—the founder of Trello, StackOverflow, and the must-read Joel on Software. Building on primitives from Information Rules, he wrote in 2022: “Smart companies try to commoditize their products’ complements.”2

What does this mean? A “complement” is a product that makes the consumption of another product easier or more likely. Blades are complements to razors; cars are complements to tires; cloud infrastructure complements SaaS. As Joel explained, it behooves any CEO to “create a desert of profitability” around their business, streamlining their product’s adoption by keeping complement pricing low and weakening peripheral ecosystem players.

Often, complement commoditization is considered a tool of the incumbent—many of the historical case studies, as we’ll see below, validate that. Launching a new feature outside the core product roadmap, purely for strategic benefit, often required a deep balance sheet. The strategy, however, works both ways. A startup seeking to enter an entrenched software ecosystem usually benefits from attacking orthogonally, solving problems that emanate from the existing oligopoly to weaken the grip of market leaders and capture end-user mindshare. As we will see, whether you are an incumbent or a disruptor, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to the strategy.

There are three ways to commoditize a complement. We’ll walk through each with historical case studies to understand how they catalyze shifts in market value flow.

Strategy #1: Nuke Pricing Power

History is replete with examples of the above strategies working, failing, and, in some cases, backfiring. Microsoft put the strategy to work perhaps more successfully than any company in history—understandably so, given the company was more or less built on a lesson in complement commoditization.

In the early 1980s, software wasn’t even considered a market separate from hardware. When PCs started taking off, IBM was so eager to be a first-mover that it launched its 5150 model with an open architecture: using off-the-shelf hardware, publishing the technical specs, and encouraging expansion cards.3 The PC landscape, including IBM and its fast-followers, would quickly descend into a knife fight, kicking off a race to the bottom on pricing. Meanwhile, Microsoft’s DOS—offering the preferred4 OS, a critical complement to PCs—skyrocketed.5 In a tale of crippling corporate hubris, IBM allowed Microsoft to maintain licensing rights…because they thought all the value was in the hardware. Thus, through hustle and a series of lucky strokes, Microsoft ended up with the dominant OS, bundled with market-leader IBM PCs, and an open license to sell to fast-followers. Over the next 5 years, OEMs would drive the majority of MS-DOS sales, as it became the standard for 300+ other PC models.6 In this case, Microsoft didn’t really commoditize anything; IBM, their complement, did the work for them.

The strategic lesson, however, wasn’t lost on Bill Gates. In 1995, 21-year-old Marc Andreessen celebrated the IPO of his company, Netscape, a shocking 18 months after it was founded. At that time, its revenues were split approximately 60-40 between two products: Navigator (its well-known web browser) and Commerce Server (one of the first web servers, enabling content hosting, analytics, security, etc).7 Marc’s vision didn’t stop at middleware though: Netscape sought to be consumer’s main “single pane of glass” for computer use, with the explicit aim to be the foundation for future application development... a destiny that, heretofore, belonged to the OS, with Windows in pole position.8

Microsoft responded by putting what it had learned from IBM into action and executing the complement commoditization strategy #1. In 1995, they began to give Internet Explorer (their browser) away for free, bundling it with Windows (their latest OS) starting the next year. Netscape followed suit, cannibalizing half of its own revenue. They hoped that free browsers would boost its Commerce Server dominance, the two being natural complements… but Microsoft’s blow had decimated Netscape’s momentum, cementing the OS as the future of the application layer.

Perhaps the most masterful stories of complement commoditization comes from Google. Like Microsoft, they’ve operationalized the play to mitigate the threat of an emergent layer between them and their consumers. We’ll highlight two cases. Following the release of the iPhone in 2007, the mobile craze was reaching a fever pitch. Apple’s dominance on the format could open several vectors of attack on Google’s core ads business: dissuade the use of Google search, open new Apple-ecosystem ad formats, and block data collection critical to targeting (some of which did eventually materialize). By open-sourcing Android, Google facilitated lower-cost smartphones, not only weakening a powerful competitor but also growing global internet access substantially—a big boon to its core search and ads businesses.

Strategy #2: Reduce Switching Costs

Google’s Kubernetes offers an example of strategy #2 with uncanny applicability to today, albeit for the cloud vs. AI infrastructure markets. By 2014, Amazon’s AWS had taken a substantial lead in 3rd party compute and storage with about 30% market share; Google was struggling with only 5%.9 That year, they undertook a bold strategy by open-sourcing Kubernetes, a technology that—to gloss over a ton of detail—made it easier to switch between cloud back-ends. They lobbied to get the other non-AWS players onboard—Microsoft, RedHat, IBM, Docker—eventually creating enough consumer pressure that Amazon was forced to support it in 2018. This weakened AWS’ lock-in, supporting Google’s recovery in market share to 12% and holding AWS steady.10 Without Kubernetes, today’s market for cloud infrastructure might not be as multifarious and competitive as it is.

Earlier this year, Anthropic announced Model Context Protocol (MCP), a framework making it easier for AI models to access and share data. Standardizing connectors should dilute the importance of 1-to-1 integrations or partnerships with any one model provider. Excellent for consumers. Perhaps also an ongoing example of complement commoditization strategy #2: helping Claude to close its 10% market share gap with ChatGPT and focus on model superiority, in the face of OpenAI’s and Google’s growing consumer application engagement.11

Before you take away that complement commoditization is a surefire road to success, we should note that not only can it fail—it can backfire. We covered Netscape’s flubbed commoditization play; some might say that was more so a too-little-too-late response than a proactive strategy. Sun Microsystems, however, offers a hallmark example of a first-mover that can dig its own grave. In the early 1990s, Microsoft began to push from PC OS into software for servers: Sun’s core hardware bread-winner. So, in an effort to make OS less relevant, it opened-sourced Java and released OpenJDK in 2007. Because its virtual machines could run Java code on any OS, Sun hoped this would reduce the switching costs of a key complement product. Textbook strategy #2, in theory.

Sun’s attempt, however, would blow up in their face. In part, yes, because they provoked the ire of Microsoft (we’re seeing a pattern here). But the strategy was fundamentally flawed otherwise. Java did succeed in eroding the stickiness and importance of the OS, making it as easy for businesses to use Sun’s Solaris as Windows, or the open-source Linux. In doing so, however, hardware became easier to commoditize, in turn reducing customer lock-in with Sun’s more expensive machines. Perhaps hardware competition was inevitable—but Sun failing to capitalize on the thriving open-source ecosystem it created with Java (and facilitated with Linux) was not. IBM’s WebSphere, Red Hat JBoss, and BEA (now Oracle) WebLogic all built $1B+ businesses predicated on Java within a decade. Sun was a no-show to their own party. In retrospect, we can glean two requisites to success in complement commoditization:

Be sure the complement you commoditize is not a lock-in for your core product.

Once you shift the flow of value, your product must be positioned to capture it.

Strategy #3: Eat the Complement

So far, most of our case studies have demonstrated how businesses use complement commoditization to subvert competition emerging between them and the end-user. New entrants, however, often look to achieve the opposite; how can startups employ these strategies to gain leverage over an entrenched incumbent ecosystem?

In 1985, Marc Benioff graduated from USC and joined Oracle as a customer success rep. He excelled, advancing into sales and becoming their youngest VP in 4 years. As detailed in his autobiography12, his time at Oracle led to an epiphany of sorts:

In the 1990s, the total cost of a low-priced CRM product for 200 employees in the first year alone was $1.8 million... the vast majority of the software is "shelfware," meaning that it is an asset that is owned but rarely used. According to research firm Gartner, as much as 65% of Siebel's licenses go unused.He was talking about Siebel Systems, the leading provider of CRM software. In 1999—the same year Marc founded Salesforce.com—it was a monster: a $40B public company with $781M revenue, growing 180% YoY, and stock price run-up 74x since IPO.13 Siebel’s stratospheric rise and ambitions had them setting sights high. Anecdotally, at that time, Siebel wouldn’t even talk to prospects without pre-approved budgets of $5M+.14 There was a clear opportunity to price under the competition, opening CRM to a massive underserved universe of customers.

Benioff faced a strategic cliff, however. Not only was Siebel increasingly entrenched, but the ancillary products required to facilitate CRM software adoption—hardware, server software, and systems integrator services—were also incredibly expensive. These complements composed a big chunk of the almost $10k / employee first-year cost of an implementation. Complement commoditization strategy #1 was out: hardware was already a graveyard, and going up against Gates or Ellison on OS was a non-starter (the latter declined building it in-house at Oracle, but he did an angel invest). But Marc saw another way.

Salesforce would eat its own complement: expand vertically to in-house all software infrastructure, selling usage on a multi-tenant client basis. His vision combined two brilliant ideas. First, the CRM market had created massive deadweight loss. Many businesses, especially sub-enterprise scale, were priced out of CRM altogether thanks to the high upfront costs. Salesforce would offer a subscription-based model resulting in less front-loaded Total Cost of Ownership, shifting expense from CapEx to more flexible OpEx and capturing a massive, greenfield SMB market. Second, in doing so, the company gained increasing leverage with a requisite complement—server hardware and software—in a way their main competitor, Siebel, could not.

This case study perfectly illustrates complement commoditization strategy #3. Founders may be thinking: cool chart Euclid, but paradigm shifts like SaaS don’t happen even day—how is this helpful? The strategy, however, extends well beyond infrastructure. Yes, Moore’s Law and great timing enabled Benioff to do something software founders a decade prior couldn’t. In effect, however, Salesforce just created a Group Purchasing Organization (GPO). By eating their complement, they made themselves the buyer on customers’ behalf, achieving several coups at once:

Taking the burden of infrastructure procurement off their customers’ shoulders, making CRM adoption fundamentally faster and easier.

Enabling them to pool and allocate infrastructure resources more efficiently.

Reducing infrastructure provider pricing power, by replacing a landscape of highly fragmented price-takers with a monopsony flywheel.

To move the example outside infrastructure, we can look at Toast. The business began as an app reliant on existing point-of-sale (POS) systems. As the founders shared in their S-1, that first angle “failed miserably… it was too difficult to integrate with legacy systems.”15 The POS was a critical complement to their software and payments vision. So they verticalized, developing their own hardware—a move that paved the way for their 15% market share today.16

Growing Relevancy in the Age of Vertical AI

Entrenched incumbents are a common challenge for vertical software businesses. As BVP put it, “by focusing on a vertical market, these companies are able to trade market size for market share and in some cases achieve 50%+ market penetration.”17 The multi-product, multi-stakeholder industry lock-in platforms are able to build helps explain why some 20+ year-old players (e.g. Autodesk or AppFolio) are still growing healthily today. This means they can be doubly hard to displace.

Like any major technology paradigm shift, LLMs have created various novel avenues for wedge products. Voice, summarization, text—we’re seeing some of the fastest-growing B2B applications today in Vertical AI. The big, ongoing question, however, is whether they can create enough defensibility to establish a lasting platform. As we’ve covered in past essays, LLM wrappers aren’t enough—after all, they are easy to build and easy to copy. Vertical incumbents—nearly every one with a system of record, from Procore to ServiceTitan—has created or is exploring LLM features, deploying a type 1 commoditization strategy to stifle competitive startups threats.

In our view, vertical AI that can graduate into a lasting platform will need to do more than innovation at a single layer of the customer value chain. At Euclid, we believe the immutable primitives of software defensibility are workflow and data (see more in our essay, “Emerging Playbooks in Vertical AI”). The strongest workflow moats can draw on multi-stakeholder network effects. By leveraging complement product strategies, we see an opportunity for founders to weaken the lock-in of incumbent products while accelerating their reach across multiple layers of customer value.

Chegg offers an extreme case study of incumbent vulnerability to LLM functionality. A vertical SaaS company providing online tutoring and textbook rentals, Chegg grew to >8M users between 2015 and 2022. ChatGPT’s subsequent launch completely kneecapped the product—effectively open-sourcing educational texts—resulting in 25% subscriber-base churn and a 93% stock-price drawdown for check since.18 A textbook example19 of complement commoditization strategy #1, even if unintentional. And a good reminder to Vertical AI businesses that data moats, in this day and age, must be truly proprietary.

Although product strategy in Vertical AI is a nascent discipline—and we’re unlikely to see anything like consensus until we have a new generation of case studies like the above—it’s clear something is working. That combination of uncertainty, promise, and early purchase is what makes it such a compelling moment for founders and early-stage investors alike.

Thanks for reading Euclid Insights! If you know a vertical software founder thinking through Vertical AI product strategy, we’d love to be a sounding board. Just reach out via LinkedIn, email, or here on Substack.

Shapiro, Varian (1998). Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy. Harvard Business Review Press.

Spolsky (2002). Strategy Letter V. Joel on Software.

Miller (2011). Why the IBM PC Had an Open Architecture. PCMag.

We had to highlight another stroke of luck for Microsoft here in case you haven’t heard the story. Gates was not the first OS developer IBM approached. Gary & Dorothy Kildall of Digital Research, however, balked at IBM’s NDA and licensing structure, dragging their feet for royalties. So IBM approached Gates. Although Microsoft didn’t have a compatible OS, they found and eventually bought one, QDOS (“Quick and Dirty OS”), from a local Seattle developer, for a total cost of $75k (just over $250k today, inflation-adjusted). This piece of code bought out of necessity would become MS-DOS: the killer product that anchored a future trillion-dollar company.

Cortada (2021). How the IBM PC Won, Then Lost, the Personal Computer Market. IEEE Spectrum.

Norman (1981). Bill Gates & Paul Allen Change the Name of 86-DOS or QDOS to MS-DOS. History of Information.

Microsoft (1986). Microsoft Annual Report. University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections.

Netscape (1995). Netscape S-1. Simson.net.

Cusumano, Yoffie (1995). Competing on Internet Time. The Free Press.

Synergy Research Group (2015). AWS Market Share Reaches Five-Year High Despite Microsoft Growth Surge. Synergy Research Group.

Statista (2024). Worldwide Market Share of Leading Cloud Infrastructure Service Providers. Statista.

Tully, Redfern, Xiao (2024). 2024: The State of Generative AI in the Enterprise. Menlo Ventures.

Benioff, Adler (2009). Behind the Cloud: The Untold Story of How Salesforce.com Went from Idea to Billion-Dollar Company—and Revolutionized an Industry. Wiley-Blackwell.

FundingUniverse (n.d.). History of Siebel Systems, Inc. FundingUniverse.

Liedtke (2000). Siebel Zooms to Pinnacle of Customer Service Software. Los Angeles Times.

Hayes (2025). How Salesforce Took Down Siebel — And Could Face the Same Fate. Medium.

Toast (2025). Toast Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2024 Earnings Call Prepared Remarks. Toast.

Feinstein, Rea (2022). Ten Lessons from a Decade of Vertical Software Investing. Bessemer Venture Partners.

Parker (2025). Disrupted or Disruptor. JLA.

Pun intended.

Thanks Bocar! Quick thoughts:

(1) Eating complements doesn't need to involve a major infra shift like Salesforce. It can be as simple as this: find a complement, something your customers also buy alongside your product. Could be a discrete service or small point solution. Offer that as a feature of your product so they no longer need to buy it.

(2) We actually think workflow moats tend to be the strongest, including network effects, product breadth and sometimes regulatory connectivity (think Tyler, Roper, Doximity, Autodesk, Shopify). True data moats are actually pretty rare, but tend to be most common in high-concentration markets like financial services, life sciences, ad tech and defense (the credit bureaus, D&B, Black Knight, Plaid, IQVIA, Google, Liveramp, Palantir)... so in some ways it can be hard to disambiguate whether the moat is actually data or more so scale and access to hard-to-get enterprises.

Really loving the posts you put out Euclid team! A great reminder that these strategies aren't just historical - they're playing out right now across the AI landscape.

I'm curious about two aspects you touched on:

How do you see the "eat the complement" strategy applying specifically to vertical AI startups with limited resources? Is there a capital-efficient way for them to execute this when competing against incumbents with massive war chests?

Your Chegg example highlights a cautionary tale, but what vertical domains do you see as most resistant to general AI commoditization? Are there specific industries where proprietary data combined with domain expertise creates a moat that even AI-native solutions can't easily breach?