Market Sizing in Vertical AI (Part I)

The TAM Uncertainty Principle

Common venture wisdom holds that venture-scale outcomes require big markets. Without one, as Don Valentine of Sequoia put it, “it’s highly unlikely you’re ever going to build a big company.”1 VCs from Fred Wilson to Reid Hoffman have evangelized this point for decades, making it about as close to universally held venture GP ideology as one can find. To some extent, it’s an obvious truth. No one can build a $10B business on a $10m TAM2, and too many leaps-of-faith between a beachhead market and “the greater opportunity” is an all-too-common red flag. Even as vertical software investors and true believers in concentrated beachheads, we agree, below a certain reasonable revenue potential, the return and dilution profile of venture dollars just won’t pencil out.

Our main problem with the “big companies require huge markets” narrative is that, without any guidance on how a founder should think about what is too small, it’s a meaningless tautology. Delivered as blanket advice, it’s probably only valuable to GPs looking to pass on a deal quickly and semi-politely. Today’s essay is the first of a two-parter: we’ll start by examining what TAM actually is and whether the data support the claim that bigger is better. In an upcoming Part II, we’ll share our perspective on the power of highly targeted beachheads and approaches for founders to stress test their market thinking constructively at the earliest stages.

Agreeing on What TAM Means

A good market sizing analysis should illustrate the revenue run-rate a business could eventually reach at a 100% penetration rate of a particular ICP3. It’s worth examining this opportunity size on a spectrum from the inception state (first product, current ARPA4, beachhead ICP) to a theoretical at-scale state, usually 5-10 years down the road (expansion of product suite & ARPA, selling into everyone that could buy it). One common method of organizing the results of said analysis is the SOM / SAM / TAM paradigm. A venture textbook classic, its most compelling feature is probably that it can fit on one slide. We’ll use the pet longevity startup Loyal5 to illustrate:

Start with a Serviceable Obtainable Market (SOM) that the business can both service with its products and obtain from a sales perspective out of the gate. We also think of this as the “beachhead” market. Loyal might consider their SOM to be the number of individual-owned senior dogs in the US * percentage seeing obtainable veterinary practices * mean gross spend per owner per dog per year on an existing important pet health vaccine (e.g. rabies or DA2PP).

Grow into a Serviceable Addressable Market (SAM), which assumes a slightly broadened product set and distribution capable of reaching newer, usually larger ICPs. For Loyal, we could imagine a SAM swapping in all individual-owned mature & senior pets in developed markets globally and assuming distribution through all vets (perhaps even D2C or retail).

As the company goes multi-product, find ways to capture more and more revenue from the ultimate Total Addressable Market (TAM), representing all revenue in the startup’s zone of value. Loyal might consider their TAM to comprise a higher annual price per patient based on a portion of cumulative pet health spend / owner * all pets in developed markets (or even humans, should their IP be eventually extensible).

If you’re already typing a comment to correct us on our misunderstanding of the TAM / SAM / SOM framework, that is precisely the point. These are such subjective terms that most VCs don’t even agree on their definitions.6 Here are the definitions we feel you should not use: enterprise value of players in the space, ROI7 users receive from the product, or some broad assumption on percentage capture of total revenue in the space. All of these are predicated on outside assumptions and disconnected from our focus: the startup’s ability to distribute and monetize.

The closer you can tie your market sizing to credible customer needs (e.g. the verifiable size of the problem, with proof of the urgency), the better. As Pear VC explains well in their Market Sizing Guide, where numbers are available, bottoms-up is best (e.g., number of customers in ICP * ARPA).8 An enterprise SaaS business, for example, should be able to characterize its market opportunity by asking a simple question, a favorite of Doug Leone’s at Sequoia: "What % of the Fortune 2000 will ultimately buy this product… and how much will they be worth to you on average?”9

Do Big Companies Need Big TAMs?

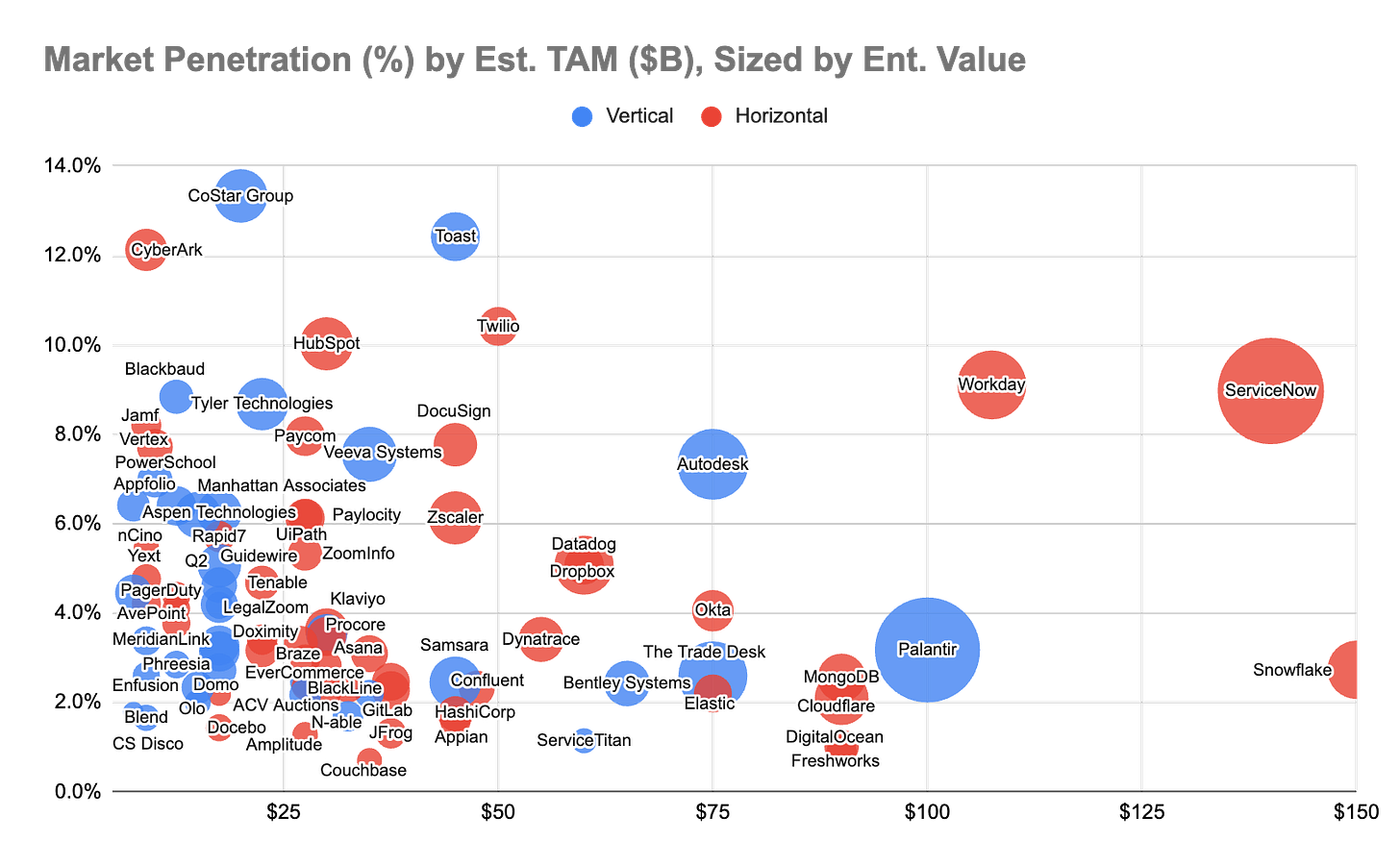

No TAM framework, of course, helps with the question, “How big is big enough?” To get at that hairy question, we set out to answer what scale of TAMs supports the venture-scale businesses in the market today. We began with public companies, which have the benefit of publicly available data and some historical narrative on market opportunity. After pulling ACV, ARR, and EV (Enterprise Value) data for ~100 public horizontal and vertical10 software companies, we layered on an average of market size estimates11 we could find from filings / research, and finally, analyzed any systematic relationship between TAM and company size.

Off the bat, we see that the lower bound for TAM on a public software business seems to be about $5B. While the larger handful of bubbles on the right side may give the impression that mega-TAMs are dominant, there are an order of magnitude more businesses below the $100B estimated TAM line than above it. Across our dataset, 93% of TAMs are <$100B, 78% are <$50B, and >20% are $10B or lower. Another immediate finding is that vertical software companies appear no more TAM-constrained than horizontal peers: mean market size estimates are just ~10% larger for horizontals. Perhaps even more interestingly, penetration rates are about the same for both.

We should also try to imagine a 4th axis, not depicted here: time. All these public businesses have had years to redefine and grow their TAM scope. Shopify, as an example, even reports on its efforts to grow addressable market in its investor presentations—they boast nearly 20x TAM expansion since 2015.12 Only six companies in our dataset have ARR greater than 15% of their total stated TAM, suggesting most businesses prioritize broadening scope before penetration becomes a rate-limiting factor. This reinforces a key learning: TAM is not a static measure and some of the best companies make market size expansion a core competency.

But what do these findings tell us about “how big is big enough” for early-stage founders? The businesses in our dataset with an average TAM estimate of $10B or less have a mean ARR of ~$480M. If the watermark for a venture-scale success is $100m ARR and we can generalize that most businesses manage to grow their addressable markets over time, it’s reasonable to conclude that market size in the mid-single digit billions is sufficient to support a venture-scale outcome. As we wrote in “An Era for Vertical Software,” one of our earliest essays, “we like to see a potential path to a $15B TAM / $100m ARR—our beachhead SAM, however, could be as low as 10% of those figures.”13 This means the floor for a healthy beachhead SOM—the universe a founder can engage from Day 1—likely lands in the vicinity of a few hundred million.

Even if smaller TAMs can support a big win, however, are they less likely to? Will they be ultimately constrained by their focus, stripped of true right-tail potential, relegated by design to micro-cap or at least sub-Decacorn status? Our analysis suggests that at least once significant ARR is achieved, TAM isn’t predictive of EV (nor of revenue multiples, which we analyzed separately). As illustrated below, the correlation between the two is weak and statistically insignificant by most standards. The qualitative answer, we suspect, is that it depends on that startup’s ability to expand its TAM over time. In other words, it’s okay (perhaps even better, as we’ll discuss in Part II) to start small… as long as there is a robust path to expansion.

Between the noise of our TAM assumptions, the small sample size, and the challenges with R-squared as a measure of correlation, we can’t hold this up as a definitive scientific finding. We think it’s directionally valid enough to substantiate a few things:

Many VCs overestimate the importance of massive TAMs early on and underweight how dynamic they are as a company grows.

At scale, vertical software companies are no more constrained by TAM than horizontal peers (not by EV nor EV / ARR).

The ability to grow TAM is more important than TAM itself.

The TAM Uncertainty Principle

Ed Sim at Boldstart put it well: “It’s not the TAM you start with; it’s the TAM you exit with.”14 Divining a TAM at exit for an inception-stage business, however, is near-impossible. Taking a note from Heisenberg: the more resolution you demand from TAM at early stages, the more likely it is that a miscalculation obfuscates true growth potential:

Shopify—discounting the potential to grow TAM via consumer surplus: Perhaps the greatest example of how vertical software businesses can leverage ecosystem lock-in to make TAM expansion a never-ending exercise. When angel investor John Phillips invested $250k at a $3M valuation in 2007, Shopify was a tool to help online stores build sites. When the founders went out to raise again a year or two later, several VCs passed on TAM: powering 40-50k online stores (at the time) seemed like a $100M market at best.15 That number of digital storefronts, of course, has grown 300x since—the latent demand was there, it just took Shopify (and others) making it easier and cheaper to unlock. As Shopify’s investor presentations illustrate nicely, TAM expansion has since become a core discipline of the business—management estimates they have grown it from $46B in 2015 to $153B in 2020 to nearly $1T today.16 Where vertical software / AI startups can achieve market expansion by unlocking latent demand via customer surplus, traditional TAM comps (e.g. CRM, ERP, BI) or customer volume assumptions may dramatically undersell the opportunity.

Uber—overlooking the market-share dominance network effects can drive. On the back of Uber’s $1.2B raise in 2024, finance professor and renowned market sizing guru Aswath Damodaran wrote a piece positing that Uber was not worth its $17B valuation.17 Obviously, in retrospect, he underestimated Uber’s TAM. As Bill Gurley of Benchmark put it, “the numerous improvements over the traditional model lead to a greatly enhanced TAM.”18 Like in Shopify’s case, it’s well known that Uber introduced a consumer surplus (in some combination of dollars and time) that grew its market. But if you look at the numbers today, market penetration assumptions are what really blew Damodaran’s numbers out of the water. Capping out at around 10% market share isn’t unreasonable, looking at historical horizontal tech businesses. Those with vertical network effects, however, consistently demonstrate an ability to go much higher—today, Uber has around 75% of the ride-share market. VCs may do well to ask the question Bill did of Uber: will this startup enable a “network effect where the marginal user sees higher utility precisely because of the number of previous customers that have chosen to use it, and would that lead to a market share well beyond the 10%[?]”19

Toast—underestimating the power of a vertical control point. In the wake of its success, it’s easy to forget that Toast began as a consumer-facing restaurant check-splitting app integrated with a single 3rd party POS.20 They had identified a real user problem, interconnected with a massive payments market. Over the course of their product discovery, however, they came to tackle an even more significant source problem (the POS itself) that opened up not only payments but a host of restaurant-facing B2B revenue streams. Toast was able to access this massive TAM expansion opportunity because, once identified, they leaned into the correct control point. A control point unlocking a “Cambrian explosion” of product offerings is a common story in vertical software. That Toast had to iterate beyond their initial product to get there is an illustration of why—in vertical software plays—domain-expert management has a leg up in navigating TAM expansion.

As vertical software investors, we at Euclid aim for high resolution on beachhead—that SOM or initial customer set a founder is attacking from Day 1. At inception stages, however, pinning a number on the ultimate TAM is much less important than understanding a founder’s vision and capacity for expansion over time. Danny Rimer at Index said it well, reflecting on missing AirBnb: “One of the biggest mistakes was to try and predict total available market size. We really view TAM as noise.”21

A Framework for TAM Expansion

In our view, founders should spend an order of magnitude more time thinking through their TAM expansion strategy than on numerical market sizing. The former speaks not only to how TAM reflects reality, but also to how the startup will credibly grow into that future. For that to be believable, however, there must be a credible story around the initial wedge as a driver of adoption and its relevance as a control point to enable downstream expansion opportunities.

At Euclid, we use the above chart to visualize TAM expansion for vertical startups. In Part II of this essay, we will unpack this graphic and walk through a framework founders can use to consider the constituent elements of their own market opportunity growth strategy: control points, product layering, monetization, customer segmentation, peripheral stakeholders, anticipated network effects, and more.

Thanks for reading Euclid Insights and happy 2025! If you’re a vertical software founder or CEO thinking through TAM, we’d love to hear from you, directly or in the comments below.

Valentine (2011). Target Big Markets. YouTube, Stanford GSB.

TAM = Total Addressable Market.

ICP = Ideal Customer Profile. See Loyal examples in SAM / SOM / TAM breakdown above.

ARPA = Average Revenue per Account. ACV = Annual Contract Value. For the purposes of TAM, these are used somewhat interchangeably.

Please note, we have no affiliation with Loyal and these examples are informed by zero research and purely illustrative. Sorry to the Loyal team if we’re wildly off here.

Pear VC (2021). Market Sizing Guide. Pear VC.

ROI = Return on Investment. In this context, we are using it to mean dollars saved or generated by customers from using the product.

Pear VC (2021). Market Sizing Guide. Pear VC.

Vernal (2020). The Market Curve. Sequoia Capital.

Chart is cut off at $150B TAM & 14% market penetration rate max for visibility. Excludes: Constellation Software ($300B, 3.2%), Shopify ($200B, 1.9%), ServiceNow ($140B, 9%), Intuit ($125B, 15.9%). Not all labels displayed.

Per our point earlier in this essay, TAMs are fuzzy. We did our best but some of these are likely off. If you find any egregious misses, let us know—we’d love to update our data.

Shopify (2023). Investor Overview Deck Q4 2023. Shopify.

Sim (2024). [Post Resharing Shopify Point from Tomasz Tunguz]. LinkedIn.

Startup Archive (2023). Insights from Startup Archive. Twitter / X.

Shopify (2023). Investor Overview Deck Q4 2023. Shopify.

Damodaran (2014). Uber Isn’t Worth $17 Billion. FiveThirtyEight.

Gurley (2014). How to Miss by a Mile: An Alternative Look at Uber’s Potential Market Size. Above the Crowd.

Ibid.

Kirsner (2012). Testing Out Toast: New Mobile App Allows Restaurants to Manage Orders More Efficiently. Boston.com.

Thornhill (2024). Index Ventures’ Danny Rimer: ‘The talent is what’s going to drive the difference’. Financial Times.

This article brought back memories of building Vungle. If you’d asked me back then what the TAM for in-app video advertising was, I’d have struggled to give a convincing answer—it was a nascent market, and mobile advertising itself wasn’t fully proven. But what we did know was the pain point: app developers needed a better way to monetize. That’s where we started.

Over time, the TAM grew because the market evolved, and we helped shape it. Mobile exploded, video became the preferred ad format, and suddenly the “small” niche we started with turned into a massive opportunity. But it wasn’t about chasing a big TAM from day one—it was about focusing on a sharp, immediate problem and trusting that expansion would come through execution and timing.

This is why I get wary when founders try to overinflate TAM projections. If I had to pitch Vungle’s TAM back then, it would’ve looked small—and a lot of investors would’ve passed. What mattered more was our ability to scale with the market as it grew. That’s why I agree with the article: it’s not the TAM you start with, but the TAM you create along the way.