The Mind-Virus of Big Venture

How VC consolidation will hurt returns & innovation

If 2022 was a year of shock and 2023 was a year of rebalancing in the venture capital ecosystem, 2024 was a year of intense dissonance. As addressed in past essays, the downward cascade of public software market repricing 30 months ago provoked a decline in volume at Series A / B, leaving a glut of richly-valued Seed-funded startups particularly exposed. Last quarter, we shared our view that the “assembly line” approach to seed-stage VC—conceived in a higher-graduation-rate environment—is likely to produce suboptimal returns in recent vintages due to this volatility.

Today, we see two perspectives struggle for dominance: (1) the empiricists, burned by irrational exuberance, capital aggregation, and over-valuation, who want to learn from recent errors and embrace a more measured venture market; and (2) the futurists, who see clear green shoots in software valuations,1 apotheosize the next big thing (AI, crypto, defense, etc.), and view a return to cottage-industry VC as naive and reactionary.

So, will 2025 be the year of the empiricist or futurist? What can the venture managers and allocators take away from the chaos of the last 30 months? While exits, allocators, and time will be the ultimate arbiters, we believe the answer is both. In today’s essay, we share our perspective and its implications, both for Euclid and the early-stage venture ecosystem as a whole.

Shifting Narratives in Venture Capital

The ongoing contraction in fundraising velocity is at the top of most managers' minds. While $71B was raised in total in 2024, more than half of all new VC AUM in 2024 was raised by nine firms. Across all PE, time-to-raise ballooned by nearly 60%.2 Perhaps most alarmingly, only 508 venture funds were raised last year, the lowest figure in over a decade.3

One interpretation of this data is that we are approaching an existential bottleneck in VC that will see the extinction of many funds as limited partners consolidate into fewer managers. Of course, fund death is not a new phenomenon… nor a necessarily unhealthy one. As Beezer Clarkson of Sapphire Ventures pointed out, only 17% of venture funds make it to Fund IV. Creative destruction and rebirth are important in any industry, especially one that has grown at breakneck speed for over a decade.

Some GPs, however, have taken this “extinction event” line of thinking further, using it to advance a very particular narrative around fund concentration. While we attribute no one manager in particular, Josh Wolfe of Lux Capital recently shared a representative viewpoint:

We expect LPs to adjust their allocations accordingly, leading to widespread contraction in the number of venture firms and consolidation of LP dollars into fewer, name-brand managers... VC is and will remain a rarified ecosystem where only a select cadre of firms consistently access the most promising opportunities. The vast majority of new participants engage in what amounts to a financial fool's errand. We continue to expect the extinction of as many as 30-50% of VC firms.4

To be clear, there are elements of this statement we agree with. A depreciation of 30% of extant funds over the next 10 years might not be unreasonable (for reasons we’ll discuss further below). Simple math dictates that “new entrants” will compose the majority of those fatalities: there are simply many more of them. A firm’s AUM and the number of funds raised to date almost certainly correlate with survivability.

That said, we find declarations like “half of all VC firms will die” misleading and—sometimes, perhaps even unconsciously so—self-serving. These “consolidation” narratives carry implications we believe are not supported by evidence:

VC is historically over-concentrated into sub-scale or emerging managers, driving a coming extinction of the majority of such funds

The structure of the asset class dictates that smaller or newer players underperform, with persistence accruing only to “established” brands

That LP capital should accordingly flow further into older, larger, or currently name-brand platforms to maximize returns

Most of these conclusions conflict with our personal experience and recent venture history. What story do the numbers actually tell? How should LPs and GPs think about industry structure and the future of small funds? Let’s start with the first implication above.

Is VC Over-Allocated to Small or New Managers?

The consolidation narrative posits that venture allocators have invested too much into newer or smaller managers, necessitating a re-concentration into more established funds. Cui bono5 offers one reason for immediate skepticism. The conclusion is very convenient for managers of large or well-known funds. Any reduction in extant fund volume, AUM, or volume of competition benefits existing VCs and their LPs.

Moreover, the assertion may be a form of value-signaling to LPs, incidental or not. Allocators are often motivated by a perception that the highest-profile or most well-branded firms in any era have better access to the best deal flow, leading them to avoid newer firms with shorter track records. “Nobody gets fired for buying IBM,” swapping in your choice of Sequoia, a16z, et al. The incentive to be a part of or associated with the in-crowd is clear. But motivations aside, what does the data say about these concentration and extinction narratives?

We don’t disagree with the “glut of small funds” point itself. The number of VC funds has grown over 200% over the last 10 years, and many of those won't exist in 5 years. As a result of the low barrier to entry in our asset class (a $5k check being technically a VC investment), a long tail of “funds” (e.g. lifestyle angels, venture tourists, ephemeral CVCs, etc.) spawn in VC boom times as predictably as they wither in contractions. As of 2023, per StepStone, almost 40% of VCs were <$25m AUM or lower. Such funds—often pilots or super-scouts—are backed in large part by HNW6 individuals who are generally less likely to re-up as LPs.7 In addition, older funds whose partnership is retiring or whose raison d’etre has faded should just as often choose to close shop as anoint a new partnership (research shows persistence of performance only with GP continuity). Regardless of the reason, the number of active funds today is down 25% from its peak in 2021.8 Another 15% decline would bring the number back in line with 2019. So whether or not you call it a glut, some contraction is a reasonable expectation. But recall that VC as an asset class has grown 160% in the same period, not to mention tech’s share of the economy—does mass consolidation and the stifling of innovation make sense in a hyper-growth industry?

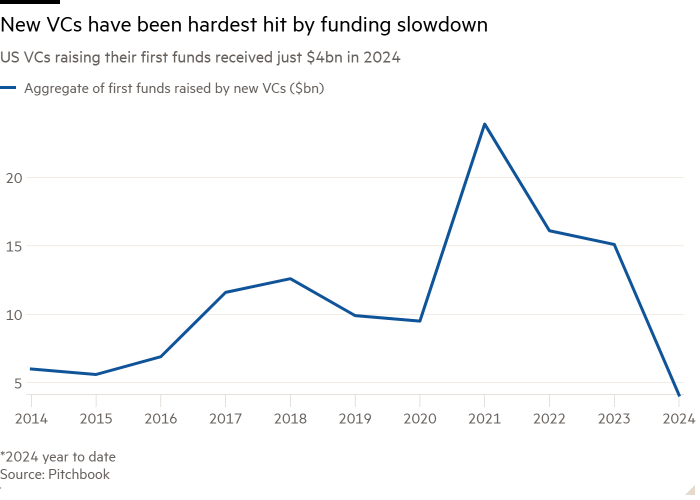

Yet, the share of US fund closings by emerging managers has shrunk to 48% of total fund count and <13% of total capital raised last year, down from 55% and ~23%, respectively, for the 10 years ending in 2019. In aggregate, only 118 small and medium-sized funds (<$500M) were raised in 2024 through Q3, collecting a total of $14B. That figure is down from 464 funds, raising $41B for the entire year in 2019. Across all of venture capital, first-time funds raised just $4B in 2024, the lowest number in over a decade.9

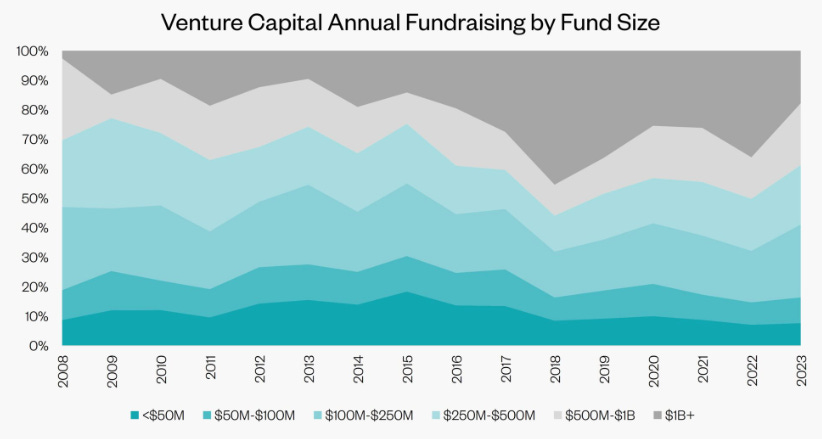

In our view, the “small VC glut” narrative misses the bigger point: allocator “flight to scale.” In the decade following 2008, >$500M funds increased their share of annual venture fundraising from ~25% to >50%. While this has receded a bit to ~40% recently, the staying power of mega funds might be surprising given their predominant roles in the excesses of 2020-21 and the depressed performance those vintages are already demonstrating.

With this context, the argument that our asset class is burdened by too many small or new funds feels specious. There is a kernel of truth there, yes. But it obfuscates the more pivotal trend: multi-stage and late-stage venture funds making a mad grab for AUM. 2016-2018 saw $500m+ funds run from an average of 20-30% of VC fundraising to nearly half.10 Paired with the overall AUM explosion during the 2019-2021 boom, it represented a deluge of capital into the hands of relatively few venture managers.

Do Brand Names Structurally Outperform Emerging Funds?

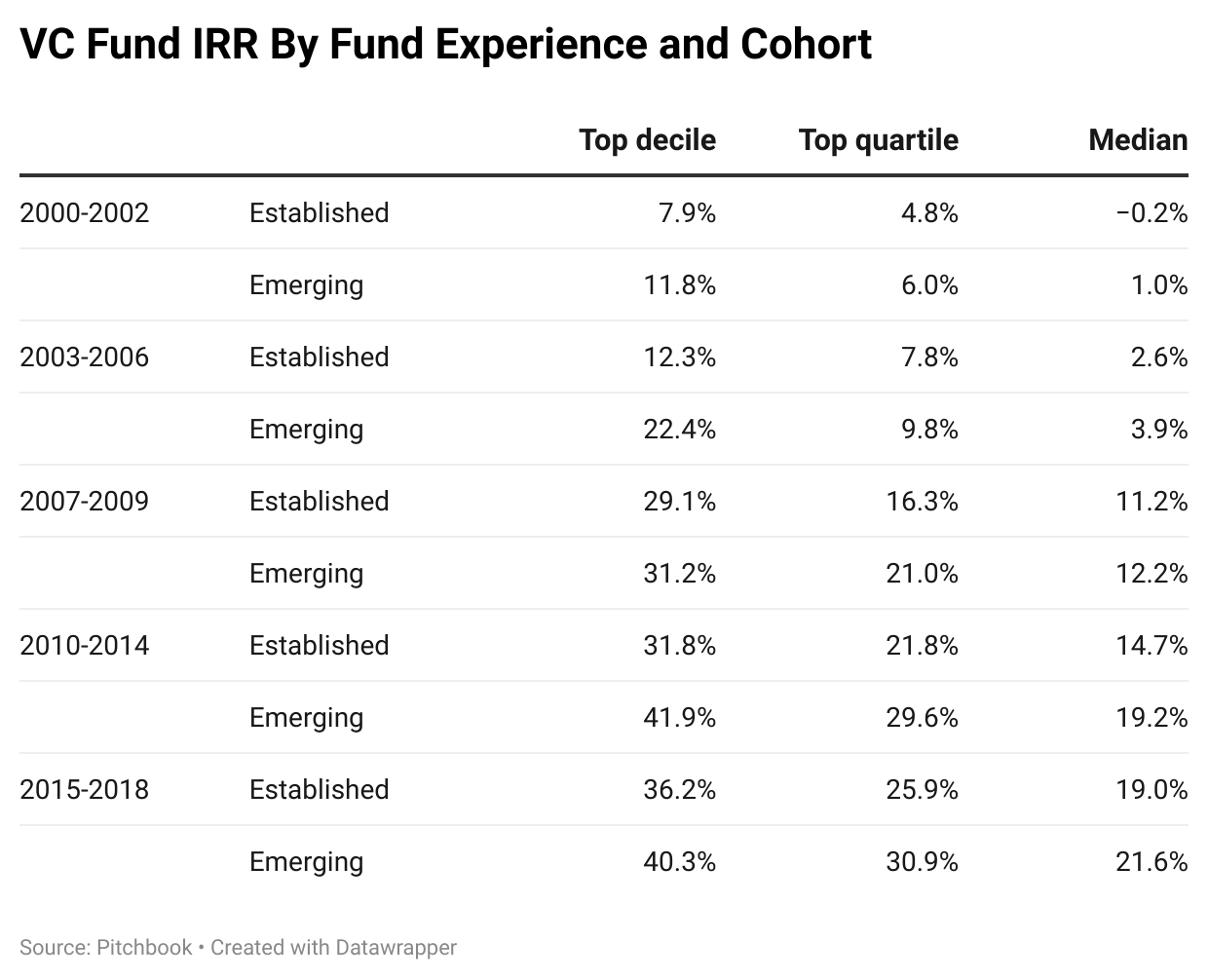

This brings us to the second implication of the consolidation narrative: big funds outperform. Over the last 30 years, the data on established vs. emerging manager performance has consistently suggested otherwise. In each vintage grouping since 2000, emerging managers (funds in vintages 1-3) have delivered a higher median, top quartile, and top decile IRR than established managers. Interestingly, the widest gap in top-decile IRR between emerging and established managers occurs in the two most recent post-crash cycles (2003-2006 and 2010-2014). In those cohorts, emerging managers outperformed by ~10% excess IRR. Some of this effect, of course, is likely driven by smaller average fund sizes for EMs. But given fund size is a strategic choice of the manager and there is generally minimal access constraint for emerging funds, why is that a relevant point? It only matters to the extent an allocator is incapable of underwriting more, smaller LP investments, or a manager is substantially increasing their fund size.

Interestingly, firm strategy was even more predictive of performance than age. From 2000-2018, the highest returning group of funds (measured by excess IRR) were specialist emerging managers (19%), followed by established specialist funds (17%). Established generalists demonstrated the thinnest edge: 11% excess IRR within top decile and just 2% amongst top quartile funds. All specialists substantially outperformed generalist peers regardless of age. Interestingly, amongst the top quartile, the established specialists achieved nearly as much excess return as EM specialists, whereas established generalists failed to meet even half of their emerging generalists peers. While causality is impossible here, this suggests to us that VC specialists may have a higher ability to drive performance persistence over time.

These findings resonate with our anecdotal experience as venture investors over the last 15 years. Many of the best-performing firms over the last decade—and managers we have learned from personally—were new formations without overwhelming brand power: IA Ventures, USV, Emergence, and Foundry, amongst others. We imagine the next ten years will be no different than any other period in venture history–by 2035, we will see significant turnover in the top 20 “brand name” VCs. So, given allocators are making a 10+ year bet when backing a venture manager, why the clear market shift post-2021 to big funds? We see two major drivers.

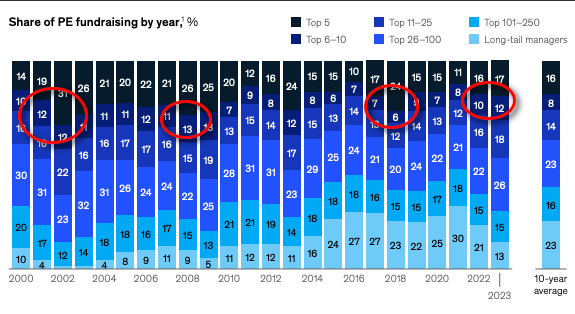

First, “flight to scale” around years of market contraction is a highly consistent effect across private equity. The above figure from McKinsey demonstrates a clear swing to top funds in 2001 & 2002, 2008, 2018, and 2022–the sole years since 2000 that the S&P 500 was negative. Allocators may proactively shift to large funds to minimize risk in uncertain times–across PE broadly, they do tend to have a lower dispersion of returns (even if they are lower on the median). Just as impactful is LPs are reupping long-held positions in brand-name funds while holding off on net-new bets given volatility. The staggering 55% drop in funds raised by <$250m funds in 2023 reflected both, with first-time fundraises dropping to historic lows.

Second, LPs may be responding to overallocation (their own or otherwise) in the 2020-2021 boom. Perhaps the most important data point in this letter is the following: per Cambridge Associates, as of 2023, VC distributions to LPs fell to their lowest point in more than 20 years. With lots of cash having gone out recently and little coming in, there is only so much money to go around. We’ll add that, while the opportunity cost to invest $1m in one VC or another is equivalent, dropping an allocation in a known fund one is already in (or one wanted to access in the past but could not) can easily outweigh the work required to find and back a net new manager.

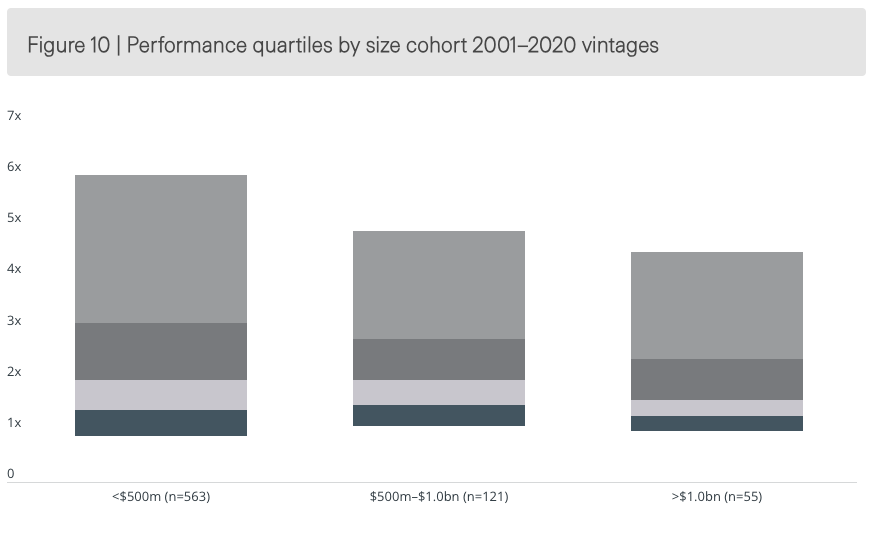

The bigger question is whether “brand name” funds are, in fact, less risky. Research from StepStone finds that smaller funds (<$500m by their measure) outperform larger peers, albeit with a higher dispersion of outcomes. That dispersion, however, seems to benefit only smaller VC funds: bottom decile performance was nearly equivalent for <$500m and >$1B shops, while ceilings were much higher for the <$500m group. So while we know (somewhat tautologically) that top percentile funds outperform and that VC has greater dispersion than other alternative asset classes, hard evidence in support of “brand name” funds falls largely to the persistence of performance: the concept that venture GPs who generate strong returns in one fund are likely to repeat the feat again in the next.

Two recent studies covering the persistence of performance in VC confirm that the effect is real and significant. The first, published in 2020, demonstrates that a highly performing VC fund is a significant indicator of future fund performance. In their words, an “[IPO] among a VC firm’s first ten investments predicts as much as an 8% higher IPO rate on its subsequent investments.” Another, published last year, confirms that persistence and strengthens the theory by showing that new strategies launched by top-performing funds succeed at a much higher rate than in other private capital segments. Per the paper, “GPs of top quartile funds repeat this feat with their next fund around 45% of the time.” Buyouts show weak and declining correlation, which could speak to the great age or sophistication of that strategy or the uniqueness of the effect in venture capital.

In the context of our question in this letter, however, it’s important to note that persistence accrues very specifically to partnerships with a high-performing fund. This means that neither fund size, age, nor “brand recognition” necessarily indicate future success (although measurement obviously requires a fund cycle or two). And while 45% is high, its predictive nature is limited for firms that posted stellar performance 3+ funds ago, perhaps with partnership changes along the way. Given the long VC feedback loop, many “brand names” may benefit less often than assumed. We would wager this is compounded by the significant fund-over-fund AUM growth of some of the most notable big brand VCs in the market today. Regardless, none of these findings back the claim that small or new funds are inherently bound to underperform—the data, in fact, mostly suggest the opposite is true.

Is Concentration Into Brand Names a Rational LP Strategy?

Finally, we will address the third implication of the VC consolidation narrative: that allocators should concentrate into “brand name” funds—after all, perhaps there are reasons beyond pure performance. To better understand the dynamics here, we wanted to look back at least one full venture allocation cycle. We chose 2006-2007, a period proximal to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) not dissimilar from the moment of retrenchment/regrowth we’re seeing today. We then analyzed the performance of the top 20 funds raised by size in 2006 and 2007. While the largest funds are not one-on-one correlated to brand name, it is a strong enough approximation. We analyzed the size of each fund relative to prior fund size, next fund size, fund performance, and the downstream fundraising success in post-GFC years.

Our analysis paints a bleak picture. On average, these largest firms raised funds that were 67% larger than their prior. From a performance perspective, none of these funds placed in the top decile of performance of their vintages, while only two (IVP and TCV) made it into the top quartile. The median performance of these funds would place them in the third quartile of the 2007 vintage.

Not surprisingly, given their performance and market conditions, their subsequent funds post-GFC were 20% smaller on average. To put that in perspective, these funds, in aggregate, captured more than one-third of all dollars raised by VCs in 2006 and 2007. The nearly $6B in shrinkage thereafter would represent 30-40% of the total dollars raised in either 2009 or 2010. In other words, at least from an AUM dollar perspective, the most prominent funds were not only the biggest gainers in the contractionary period but also the biggest losers in the following years.

Beyond their fundraising challenges in recovery years, 11 of these 20 “big brand” firms went through a meaningful restructuring event post-GFC: strategy pivots, team shake-ups, rebrands, and/or wholesale shutdowns. Some of those challenges stemmed from generational transition issues, as we still see today. Others more than likely emerged from poor investment theme selection (e.g., heavy allocation into cleantech, semis, etc.). We believe the evidence suggests that significant increases in fund size also played a major role in depressing performance and future prospects. In any case, one thing is clear: the “brand-name” firms were neither the safe, nor most performant venture bets in this timeframe.

The Implications for the Innovation Ecosystem

In examining the postulates of the “venture consolidation narrative,” we find it mostly fails to hold water. Nonetheless, it has been the reality in VC for some time, and we will have to grapple with the consequences. In our estimation, the gravity of brand-name VC has had deleterious effects beyond just LP performance, spreading poor practices throughout the early-stage ecosystem as a whole. Allocator preferences have created strong incentives for smaller funds to mimic large-fund behavior. These behaviors have become so prevalent that some EMs have predicated their entire strategy on investing upstream of or even alongside mega-funds.

There is no doubt that the quality of funds marking up a portfolio can be a leading indicator of success. All managers should be cognizant of “next buyer” psychology. Deducing early-stage investment priorities from downstream brand-fund preferences, however, is like stock picking based on last year’s S&P 500 performance. At best, it leads to a vicious cycle of homogenous investment themes, like an LLM experiencing algorithmic collapse… the “VC monoculture” Bryce Roberts warned about over a decade ago.11 At worst, it leads to a whole lot of new GPs chasing the wind. After all, large funds can do things EMs simply can’t. They have the ability to make a multitude of early option bets while reserving the vast majority of their capital for later stages. While their investment roadmaps are well publicized, they are, of course, influenced by what they want to invest in today (at Series A-Growth). EMs, whose first checks are usually their most significant driver of alpha, should be concerned with what will succeed—and hence attract downstream capital—tomorrow. And a lot changes in one year, let alone three, four, or five years down the line.

The longer-term concern with capital concentration into a handful of funds is its potential to weaken the link between the innovation ecosystem and free market forces. Just as the “assembly line” approach to venture capital risks producing suboptimal outcomes for EMs, there is an equally harmful impact at the company, or founder, level. Growing capital homogeneity, in our view, leads founders to aggregate around consensus ideas and themes. Some of these incentives are subtle (e.g., a slight shift in approach or model), while some are more overt (e.g., ideas flowing from VC to founder rather than the inverse, perhaps even through direct incubation). Explicit requests for startups are increasingly common. While we aren’t suggesting nefarious intentions, we see these as unintended consequences of the “VC monoculture.”

A study in 2023 aimed to quantify the impact of “startup catering,” where founders work on the problems they believe VCs will fund.12 It demonstrated a 27% increase in funding probability for “catered” startups vs. the mean. We believe, however, that startups don’t win by VC consensus; they win by market consensus. History has shown those often don’t align. And as we discussed in a previous essay on navigating “Vertical Hype Cycles,” it also leads to booms and busts in categories. We believe that both logic and history dictate that performant early-stage funds—whether “contrarian” or not—invest with first-principles thinking.

It is unavoidable that capital allocation strategies (whether VCs or LP) are backward-looking to some extent—we all aim to identify the repeat patterns of success. If duplicating the same old approaches were consistently successful, however, private capital would be entirely monopolized. As Kyle Harrison from Contrary has repeatedly pointed out, these large brand-name firms are playing a different game than traditional VC:

This pursuit of "2% of the biggest number" is consuming venture capital. Empire firms are eating the asset class. And with it, the role of adventure capitalist is being subsumed by the importance of asset management…People taking risks alongside founders to help build generational businesses.13

Differentiation, especially for emerging managers, will not come from imitating the asset manager’s playbook. While we often think of differentiation at the portfolio level—driving the “right to win” individual deals—the same is applicable at the fund level. Over repeated cycles, a VC manager’s ability to find and win the best opportunities defines their “right to exist” and will separate the good from the great in this increasingly competitive environment for capital, investments, and mindshare.

From founding, our goal at Euclid has been to build a lasting venture capital franchise with the ability to deliver top-performing funds consistently. Critical to that story was our belief in two key assumptions:

Vertical software is a large, important, and enduring category underserved by an early-stage capital ecosystem that is underdeveloped and structurally disadvantaged to back the best opportunities.

As GPs, we can leverage a specialized 15-year track record, network, and playbook to access the best early-stage opportunities in our category while building that success into a compounding brand advantage over time.

Future emerging manager fundraising prospects aside, our analysis bolsters the “macro” case for our “micro” strategy at Euclid. Focused, specialized, differentiated strategies outperform. But our goal—building the leading early-stage fund for vertical software—demands more than a different tack on scope or stage. Euclid’s ultimate differentiation, as with any fund or company, rests on our ability to execute our vision.

We appreciate your continued support of Euclid Insights! If you’re a founder, investor, or LP spending time in vertical software, we’d love to trade notes—look forward to hearing from you by email, LinkedIn, or in the comments below.

Ball (2024). Clouded Judgement 1.16.25 - December Inflation. Clouded Judgement.

Falconer (2024). Private Equity Fundraising Timelines Hit a Record 19 Months in 2024. Buyout Insider.

Hammond (2025). Number of US venture capital firms falls as cash flows to tech’s top investors. Financial Times.

Cui Bono? = “who benefits?” in Latin. Often used in investigatory contexts.

HNW = High Net-Worth.

StepStone Group (n.d.). Venture Capital: Shedding the Access-Class Label. StepStone Group.

Hammond (2025). Financial Times

Various (2024). Financial Times & PitchBook.

Chronograph (2024). The Evolution of Venture Capital Fund Sizes. Chronograph.

Roberts (2011). Fear of a VC Monoculture. Fortune.

Li, Ellen (2023). Startup Catering to Venture Capitalists. American Finance Association.

Harrison (2025). Venture Capital Unbundled.

Bain & Company (2024). Global Private Equity Report 2024. Bain & Company.

Cambridge Associates (n.d.). Have Public Market Returns Permanently Eclipsed Private Market Returns. Cambridge Associates.

Carmean, Hu, Gao, Le (2024). Q2 2024 PitchBook Analyst Note: Establishing a Case for Emerging Managers. PitchBook.

Carta (2024). Recent VC Fund Performance Q3 2024. Carta.

Harris, Jenkinson, Kaplan, Stucke (2023). The Dynamics of Private Equity Fund Performance. ScienceDirect.

Kauffman Foundation (2012). We Have Met the Enemy...and He Is Us: Lessons from Twenty Years of the Kauffman Foundation’s Investments in Venture Capital Funds and the Triumph of Hope over Experience. Kauffman Foundation.

McKinsey & Company (2024). McKinsey Global Private Markets Review 2024. McKinsey & Company.

Nanda, Samila, Sorenson (2020). Market Liquidity and Public Market Returns. ScienceDirect.

Another great article as always. I’d like to add a few other perspectives.

The cards are generally stacked against first time fund managers. I can speak to this as someone who ran a small VC fund but decided not to raise Fund 2:

1) They lack sophisticated legal counsel and fail to negotiate special terms that I often see larger funds ask for such as pro-rata, ROFRs and warrants.

2) Larger funds have the infrastructure to keep a tab on their portfolio and often can take board seats to ensure their interests are protected. The ability to follow-on in a meaningful way can change the trajectory of a portfolio company

3) Smaller funds often raise from friends / high net worth individuals. To raise a good fund 2, you need institutional LP relationships and family offices who can keep investing in you over future vintages and write a few $M minimum.

The last point was the main reason we decided not to raise Fund 2. Our LP base were industry experts (for our proptech fund), in many cases they could barely write $100K and it was absolutely exhausting having to work so hard and take so many meetings for such a small check. You need 100 of committed LPs for a $10M fund if you assume a $100K check - that’s a lot of relationships to manage!