The Seed-Stage Reckoning

And its implications for Vertical Software founders and investors

The early-stage startup fundraising market is in the midst of a slow and painful rebirth. It has taken this long for the sharp public-market feedback of 2022 to start changing the behavior of seed-stage GPs—and still, many still act like a return to 2019 is around the corner. It isn’t. Nor would that be a good thing, in our view. Where are we actually in this adaptation cycle? What mean are we reverting to? In today’s essay, we’ll unpack what we’ve been seeing over the last 18 months and suggest what this reckoning might mean for founders and VCs both.

Graduation Rates & Portfolio Performance

Graduation rates—the percentage of businesses in a portfolio that raise the next financing round—have been a VC metric since we entered the industry 15 years ago. While DPI is the metric, of course, managers need nearer-term barometers to gauge mid-flight performance and differentiate their strategies. While the graduation rate to Series A is still commonly hailed as a leading indicator alongside TVPI, there are reasons to believe that rates may face headwinds as startups of the prior five years run into tightening downstream expectations. Charles Hudson, Managing Partner of Precursor, covered this well in a post late last year on “The Big Reset in Seed to Series A:”

For the past ten years, the near-term goal for most seed-stage companies has been to raise a Series A round of investment. Good venture capital firms saw 50-75% of their seed investments graduate to Series A rounds during this time… In many ways, graduation rates became a key part of the marketing story around seed-stage firm performance.

At Euclid, our goal is to see the best of a basket of highest-quality teams and ideas through to exit. Given the high-growth profile of the businesses we target, those journeys of success require downstream seeds, Series As, and (often, but not always) some measure of growth capital. Naturally, therefore, graduation rates matter.

Optimizing fund strategy for graduation rate, however, is a risky proposition that is getting riskier. An unintentional consequence of such an approach can be the “assembly line” approach to early-stage venture capital. A high volume of initial investments requires intense systemization–and often simplification–of the picking process. Many firms rely heavily on thematic strategies that focus dollars into “hot” or fast-growing sectors. As we discussed in a previous essay on navigating “Vertical Hype Cycles,” however, booms are fickle.

So, while conveyor-belt investing may produce impressive short-term performance on paper, it will inevitably underperform without a consistent way to consistently foresee cycles (and anyone who is probably better advised to quit immediately and launch a hedge fund). Recent market downturns in micro-mobility, crypto, fintech, and supply chain tech serve as cautionary examples. Recently, we are proceeding with caution witnessing the rapid growth of capital allocated to defense and climate tech. Being early and right in a market without winners is the right goal, but oversaturated capital market environments can drag down sector returns and be a death blow to companies that previously relied on them.

Sudden shocks to downstream capital velocity also pose a structural challenge for the high-volume model. The sort of fund built to manage a massive portfolio of deals has less time and resources to spend on each pre- and post-investment. Without rebuilding their fund, the conveyor-belt investor is unlikely to have the time to maintain pace while improving their top-of-funnel filtering to meet stricter criteria and shepherding businesses through more nuanced Series A processes. Equally, with ownership often being a trade-off for high-volume fund models, increasing early-stage mortality requires either larger winners or more of them to maintain performance levels. That tightening environment has become a reality over the past 24 months: while ~30% that raised a seed in 2018 and 2019 raised a Series A within two years, that figure is below ~15% for the 2022 cohort, a decrease of 50%.

This does not mean, of course, that we ignore graduation rate as a metric at Euclid (or that high-volume fund models cannot work in this new environment). Like most venture firms, our fund model makes assumptions on how many portfolio companies will succeed through financing rounds. Like interim markups, graduation rates are instructive, but we do not view them as deterministic for a concentrated strategy like ours.

Our fund thesis is built around investing in a small number of founders each year that we believe will build important companies. We develop independent conviction in each founder, idea, and market—if we don’t believe an opportunity can be a category-winner and fund-returner, we don’t invest. When we do invest, we are all-in—on average, 10% equity owners and working for our founders on a weekly basis or more. Beyond capital, significant time and resources are dedicated to each company to ensure each Euclid founder is the top decile of Series A candidates, regardless of whether the prevailing graduation rate is 20% or 50%. When a single Euclid portfolio company achieves a strong exit, moreover, it is fund-making.

In large part, high graduation rates can reflect downstream dry powder as much as company quality. Ultimately, building an attractive, impactful and creating exit demand is all that matters. Mid-tier businesses able to raise several rounds of capital, that hit the same wall only later in their lifecycle, are no better off. This is why we allocate our capital to ensure concentration in a small number of the highest-quality assets and maximize their potential on an ongoing basis—something typically difficult for volume-driven, diversified strategies. Perhaps the massive current overhang of unicorns (or former unicorns) now staring down slimmer exit appetites suggests that, at some point, graduation rates were too high. Venture capital is a game of outliers, not averages.

The Seed Reckoning is Upon Us

As discussed above, the graduation rate from seed to Series A has declined precipitously in the wake of the 2020-2021 boom. What does the data tell us about why? The simple answer is that the volume of VC-backed startups has exploded over the past few years. According to Carta’s internal data, 518 SaaS startups received seed funding in 2020. The number of seed-funded SaaS startups more than doubled (1,111 and 1,037) in the following two years. If we apply the cohort graduation rates to the aggregate funding data, we see that outside of the noisy 2021 window, the number of SaaS Series As was effectively flat. 155 of the 2020 cohort of startups have raised a Series A compared to 145 companies from the 2022 cohort.

Despite this glut of seed-backed SaaS companies, SaaS seed funding in 2023 only marginally declined, down 6% from 2022 with 978 startups. Pre-money valuations also grew during that time frame—$12M in 2021, $15M in 2022, $14M in 2023, and reaching an all-time high of $16M in 1H2024, according to Carta’s internal data.

This is highly counterintuitive at first glance: SaaS seed graduations are at a historic low, yet SaaS seed valuations are at an all-time high. As of Q2 2024, the median pre-money on core Seeds was $14.3m—just 1% lower than the peak two years ago. The simple explanation is that a glut of capital has flooded the seed stage that needs to work its way through the system. First, many new seed funds were raised in the overheated boom-era vintages–this included many emerging managers and a spate of mature seed players raising substantially larger funds III-V. Second, some later-stage funds sought to distance themselves from moribund growth-stage markets by shifting earlier. The result was a seed market that got larger and more expensive without a commensurate increase in standards—even as a disquieting cooldown in Series A activity emerged in mid-2022.

Perhaps the ~30% decline in new investments in 1H’24 marked the start of a return to normal for the SaaS seed market. Cohort analysis makes clear, however, that the reckoning is still underway. Startup shutdowns hit a record high in Q1, increasing 102% YoY at the seed stage and 58% YoY overall. These numbers would probably be higher if many firms had not earmarked substantial capital for bolstering existing portfolios. According to Carta’s internal data, 42% of seed-stage financings were bridge rounds in Q1 2024, a higher percentage than in any other quarter this decade.

A New Normal for Top-Tier Downstream Funding

Another bizarre artifact of the early-stage market is that Series A software valuations have never been higher. So, despite a meaningful increase in the supply (i.e., seed startups) and a reduced number of consummated Series As, the median SaaS Series A valuation today is 70% higher than it was in 2019 ($54M vs $26M). The 75th percentile valuation is almost 2x higher ($76M vs $40M). Valuations, for both Seeds and As, are effectively back to 2022 highs.

The Series A valuation buoyancy might simply reflect a flight to quality. In other words, Series A investors now require more traction (anecdotally, nearly 2x) and unimpeachable metrics. A large amount of dry powder is set aside for fewer “breakouts,” driving up check sizes and, thereby, valuations. For perceived premium deals, more firms around fewer deals may drive a feedback loop on price point.

How about further downstream? With more vetting and concentration on high-quality Series A assets, you might expect Series B graduation rates to grow, especially as the graduation rate from Series A to B for SaaS startups has declined materially since the 2020 peaks. We haven’t seen this quite yet and likely need 12 months more data to opine.

While the looming filter at Series A solicits panic in some quarters, we will paint a different picture. Like the seed-funding market, the declining graduation rate speaks more to excesses of the 2020-2022 venture market than the go-forward fundraising environment. Boom-era cohorts were lower quality: diligence was infrequent, traction overlooked, and deal pace unsustainable. To use one illustrative data point, 2021 had nearly 60% more SaaS Series A fundraises than 2020. More companies raised than should have, and those that did got more dollars than they should have.

These excesses will take time to flush through the system. The healing process–however painful and lengthy–is well underway. Q1 2024, for example, saw the number of down or flat rounds as a proportion of all venture deals reach an all-time high of 27%. At Series A, bridge rounds accounted for 43% of all financings. It’s important to remember that all these figures—bridge rounds, down rounds, shutdowns—are lagging indicators. The downturn in the fundraising market is now more than two years old, which means that going forward, startups that are fundraising are more likely to have last raised after the slowdown in the 2H of 2022. While that does not bode well for portfolios from those vintages, they are not necessarily indicative of the success of early-stage businesses funded over the last 24 months.

Another reason for our cautious optimism for the downstream fundraising environment is that VC dry powder is at a record high >$300B entering the 2nd half of 2024. Despite the mega-cap fundraising of A16Z, General Catalyst, and others, 43% of the total sits in funds with commitments of $500M or less. Over 60% of the total resides in 2022 and 2023 vintage funds. We believe capital deployment will accelerate 2025 and beyond into new startups as internal bridging taps out and the noise of the boom era subsides.

Several consequential factors play a role here, of course, including the upcoming presidential election, Fed treatment of interest rates beyond September’s rate cut, and timing on the IPO window cracking open. While timing the market is impossible, the current reset puts us on pace with the historical 3-5 year recovery window following a venture bust.

Why We’re Focused on Inception-Stage

Our founding thesis for Euclid was predicated on a market opportunity that we had identified over our 15+ years of investing: despite Vertical SaaS being a large and distinct category, VCs struggled in identifying and evaluating opportunities: 1) in new, emergent markets without prior winners; 2) ahead of obvious traction. And while there are many great funds that back these companies at seed and later, we felt there was a growing funding gap ahead of those milestones. But what is that gap?

Jeff Becker with Antler together the team at Carta put together this great analysis measuring the “Hidden Years of Inception” for founders. The data shows it takes software founders between one to three years from founding to raise a priced seed. What is equally surprising is the data is similar for accelerators. According to Jeff’s analysis “across 23,241 companies between 2013 - 2019 who participated in accelerators, the average company age was 3.1 years old, and revenue was $114,437.”

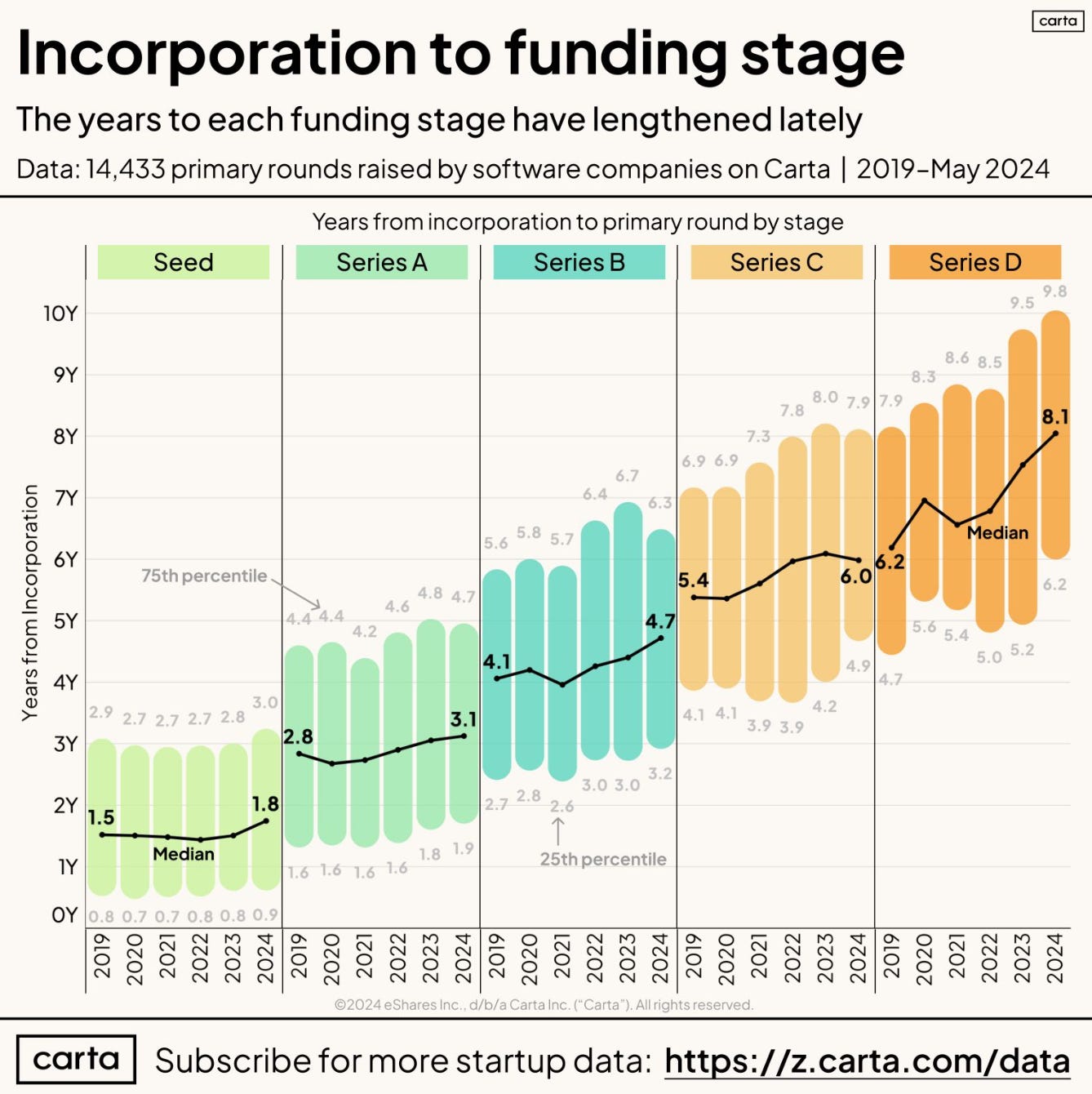

Confusingly, the “first-check” tagline is now used by funds of all types in the pre-Series A spectrum. This dislocation isn’t just a quirk of the current oversupply of seed capital—it’s also a byproduct of the state of the venture capital industry and stakeholders furiously re-branding to drive differentiation. The earliest frontier of venture, once dominated by angels and accelerators, remains confusing and underdeveloped. We believe this datapoint is a great representation of what is occurring: the median time from founding to seed has grown from 1.5 to 1.8 years over the past four years, yet the median between seed and Series A has remained at ~1.3 years over that time frame. This feels highly inefficient: the “median” founder would likely raise three times within the first 1.5 years of company life: formation (angel), pre-seed (6+ months), and seed (18+ months).

Our belief is that top-tier founders see the value in partnering with an institutional investor from inception, accelerating their journey to building enterprise-value, and bypassing the hassle of angel syndicates and the dilution of accelerators—while still selecting an engaged and aligned partner. As we talked about in our essay on PMF, we don’t mind investing pre-product and pre-revenue, but we do care about underwriting “identified market demand” as we highlight in the chart below.

In this muddled early-stage environment, naming conventions are far less useful than defining the role venture capital should play in company development. In other words, each funding round (or lack of funding round) should be purposeful. In general, but especially in vertical software, we do not think the market discovery or evaluation phase should be capital-intensive. Early-stage VC is expensive. As such, it’s best reserved to reach discrete milestones, where more resources can drive rapid increase enterprise value. It’s hard to argue that market discovery is one of those use cases—if the founder can’t do it solo, there isn’t much to talk about.

Of course, there has always been a tier of founders that could raise near-Series A rounds at formation. Whether this works better is very difficult to answer with data, but it remains the exception and not the rule in any case. And there will always be accelerator-incubator partners to startups that desire those programs, whether due to a desire for infrastructure, process, community, or marketing. Y-Combinator, South Park Commons, Antler, Entrepreneur First, and others have built strong franchises doing just that. We do see a growing universe of founders, however—perhaps more prevalent where CEOs have steeped industry networks—that prefer to skip the constraints and tuition of that model.

In vertical software specifically, some of these founders with discrete visions are reaching Level 2 of PMF at or near company formation. Their domain experience and deep network in the category allows them to sell way ahead of product. Our conviction in this accelerated start reflects in our strategy—all of our investments have occurred within ~3 months of company founding. The “n” is small but our conviction is even higher that providing those teams with access to institutional capital and networks from formation enables them to accelerate their path to market, capitalize on established demand, and scale enterprise value creation. For vertical software founders especially, we also believe it can be the most dilution-efficient way to reach higher levels of Vertical PMF and shrink what seems to be an ever-expanding time-to-Series A.

After all, early-stage VCs and founders share a love-hate relationship with downstream fundraising. We’ll end as we began, with a succinct point from Charles Hudson (this post). We share some version of it with our founders before we invest.

Dilution is our enemy, too. We are aligned with founders on capital efficiency because dilution is our enemy, too. We will make the majority of our financial returns from our first check investment decisions, so minimizing dilution will amplify the return on those investments.

David Packard once wrote that "more businesses die from indigestion, than starvation,” and while that remains great advice for founders, we also think its also a timely reminder for the early-stage ecosystem as a whole.

Thanks for reading! And thanks to the various thought leaders below for their inspiration and analysis we relied on.12345 As always, we’d love to hear your thoughts on our work: please shoot us a note or reply in the comments.

Hudson (2023). The Big Reset in Seed to Series A Graduation Rates is Real and Permanent. Venture Reflections.

Walker (2024). State of Private Markets: Q1 2024, Carta.

Walker (2024). State of Pre Seed: Q1 2024. Carta.

Walker (2024). State of Private Markets: Q2 2024, Carta.

Walker (2024). VC Fund Performance: Q1 2024. Carta.

Walker (2024). Series A Graduation Rate Chart. Carta.

Becker (2024). The Hidden Years of Inception Stage. Monday Morning Meeting

Pitchbook (2024). 2024 US Venture Capital Outlook: Midyear Update. Pitchbook.

Teare (2023). These 3 charts show it’s not easy being a seed startup these days. Crunchbase News.

Appreciate the insights here! As we shift toward leaner seed rounds, I wonder how it will influence innovation at the earliest stages. Will we see more focused problem-solving and less chasing of 'unicorn' status too early?