The Quiet Death of VC-Founder Alignment

How AI and AUM are shifting investor incentives at the early stage

As a founder, bringing a VC onto your cap table involves many considerations: check size, valuation/dilution, value-add, and whether you can tolerate working with this person for a decade. But one critical question often gets less airtime:

Do this investor’s priorities actually align with my own?

In other words, how much do they actually care about my success? Will we ultimately agree on the right outcome? Will they work for us like their jobs depended on it… or treat me like my job depends on them?

The Great Misalignment

“I think it’s bad for the ecosystem that we are going to remove all the small and middle outcomes and just play grand slam home run ball all day long. But that’s what it feels like to me. And it feels like we didn’t learn anything from the ZIRP days.”

—Bill Gurley, Colossus Interview

This issue of founder-investor alignment is multifaceted. Some factors are subjective, like the “stage of life” or hunger of the fund / GP, whether they have strategic interests separate from financial ones, or whether they’re a “venture tourist” unlikely to be around in a few years. But many of the most critical drivers are quantifiable. Fund size, check size/ownership stake, and exit size ultimately dictate which deals a VC must care about most, because those factors—extrapolated across their portfolio—drive their returns.

Founders are increasingly recognizing misalignment as a growing concern. VC fund sizes have grown dramatically in the last decade, as we’ve covered extensively. To put their war chests to work, large-AUM funds have expanded into historical PE territory with new rollup strategies. But they’ve also moved upstream into the early stage with programmatic initiatives like a16z SpeedRun, Lightspeed Launch, and Sequoia Arc. The net result is that pre-Series A rounds have expanded dramatically over the last 12-24 months.

The second-order effect is an increase in mega-funds on early-stage startup cap tables. Sapphire Ventures recently put together an analysis of the “market share” of seed rounds by mega-funds.1 It’s perhaps unsurprising that mega-funds lead or co-lead 41% of $5M+ seeds and the majority of $15M+ seeds today. But mega-funds also lead or co-lead 20% of seeds <$5M. They even lead 11% of $1-2M seeds.

Sometimes, a big fund in a seed makes sense: the founder is raising $20M+, with burn and next-round expectations in-line with Series A style expertise; the GP was a previous backer of the founder and there’s an existing trusted relationship; or the company is already growing so quickly that “skipping a round” is logical. It bears repeating, though, that mega-funds are leading one-fifth of all “classic” sub-$5m seeds today and over one out of ten $1-2M seeds (which many would consider to be pre-seeds).2 In many of those cases, the founder’s attraction is the fund’s brand. While not unreasonable generally—at the seed stage—this overlooks the very real potential for harmful founder-investor misalignment.

The issue is also no longer confined to mega-funds. Some mature seed funds have grown to the point that AUM demands completely different incentives vs. just 5 years ago. Characterized roughly: they have too much AUM to be doing $1-2M pre-seeds, but perhaps not enough brand / pricing power to consistently compete with platform funds for Series As. So, feeling squeezed, they: (1) take the seed deals they’re good at and expand them; and (2) consider whether they should write seed-sized checks (at seed-stage valuations) at pre-seed stages. Maybe this works out in some founders’ favor—after all, many of these seed GPs are excellent. But for founders, the extent to which seed manager incentives have shifted is probably not top of mind. For better or worse, venture brand perception evolves slowly.

AI is only accelerating this early-stage “piling on” effect. Natural to all paradigm shifts is a moment of confusion and fear amongst investors as they adapt—arguably, we’re seeing knock-on effects of that moment post-LLMs. AI has enabled some unprecedented growers. That’s good (and part of nearly all managers’ pitch to LPs, no doubt). But aside from the fact that revenue quality in some of these prosumer, PLG-heavy AI companies is unproven, the “$0 to $10M revenue in a year” startup is still scarce (at least in high-margin, application-layer AI). VCs are afraid that the “triple-triple-double-double”—a VC folk benchmark for excellent YoY startup revenue growth—is dead in the water. Moreover, how can a seed VC access these “shooting stars” when they hit $10M+ ARR on barely any capital raised? If they leave sub-$3M rounds to pre-seed funds, there is no seed round for them to lead before the Series A platforms flood in.

It reminds us, in some way, of the classic Silicon Valley skit: revenue (or any traction metrics) is bad. If a company went $0 to $10M ARR, it’s beyond them; if a company has a few million ARR it’s not a shooting star. Yet capital must be deployed. So, the manager thinks: instead of the seeds we normally lead, why not give $5M to a pre-revenue company that could be a top 0.1% grower…? While we’re simplifying it to the point of parody, there is an undercurrent of truth to this logic in the current environment.

Raising from a misaligned investor can create lasting, irrevocable issues for a founder. A $400M exit, for example, may be transformational for a founding team—perhaps even the best possible outcome—but a rounding error for a GP who needs $1B+ outcomes to drive returns on big AUMs, is OK with a few zeros, and has the investor rights to veto. On the flip side, small checks can be misaligned too: either because big funds lobbed an option check early and need to buy up to make the position matter, or because a party rounds yielded no single investor with enough skin in the game to truly step up. In short, alignment matters—and it’s worth dissecting the math behind investor incentives to understand how much any given VC will need your company to succeed.

Below, we’ll share our analysis on how fund size, ownership, and exit potential underpin a VC’s alignment with founders. We’ll also share our view on how both AI and the capital environment are shifting these dynamics in real-time at the earliest stages. The goal is to equip founders with a lens for evaluating VC partners to ensure they don’t find themselves on the back burner down the road when it counts.

Why AUM & Check Size Dictate VC Alignment

“If you look at the distribution of outcomes in a venture fund, you will see that it is a classic power law curve, with the best investment in each fund towering over the rest, followed by a few other strong investments, followed by a few other decent ones, and then a long tail of investments that don’t move the needle for the VC fund.”

— Fred Wilson, Power Law and the Long Tail

Venture funds succeed on a power-law basis: a few big winners typically drive most of the returns. A common portfolio heuristic—similar to Fred’s take above—is that one-third of investments fail, one-third barely return capital, and the top third produce most of the returns. To deliver attractive results to LPs, a fund usually needs to return at least ~3× net its total size (and many early-stage managers aim for 5×).3 This fundamental math ties directly into alignment: bigger funds need bigger exits to hit their returns thresholds.

We wrote about this phenomenon at length in “We Have Met the Enemy and He Is Us,” discussing Josh Kopelman’s fund arrogance score. The score analyzes the percentage of annual VC-backed exit value that a venture fund would need to capture to beat a gross cash-on-cash return hurdle. We highlighted three examples: the average of the top 5 and top 9 largest funds raised in 2024, as well as the rumored $20B a16z fund.

The requisite scores on the above funds would require Herculean assumptions regarding fund performance and the total exit environment. The above rumored a16z $20B fund, for example, registers an astronomical arrogance score (even at a generous 3-year deployment cycle). Given that their last announced fundraise was in early 2024, one could argue the score should be twice as high (requiring more than 100% of proceeds possible from projected exits). And remember, these figures are calibrated around a 3x gross (~2x net) fund, anemic by VC performance targets.

—Euclid Insights, “We Have Met the Enemy and He is Us”

But of course, it’s not just fund size that matters. The size of an investor’s check—and resulting ownership stake—is the second leg of the stool. Low ownership means either: (1) if a big fund, low impact on the fund’s returns; or (2) if a small fund, a higher bar for exit size to make the deal a fund-returner. The former can lead to issues around follow-ons and signaling risk4. Both can signal low attention and misalignment around exits or follow-ons.

Which brings us to the third leg of the stool: scale of outcome. When VCs invest, they are generally underwriting the company for a potential exit of a specific size. The later-stage the fund, the more likely they’re doing this math explicitly. That underwritten outcome maps to their return targets. While everyone is happy with multi-billion-dollar outcomes, 9-figure exits are fertile ground for the most regrettable cases of founder-investor misalignment.

The Math Behind Investor Alignment

Let’s quantify the alignment issue by asking the following:

What exit value would return a VC’s fund? Or at least, a big enough chunk to matter?

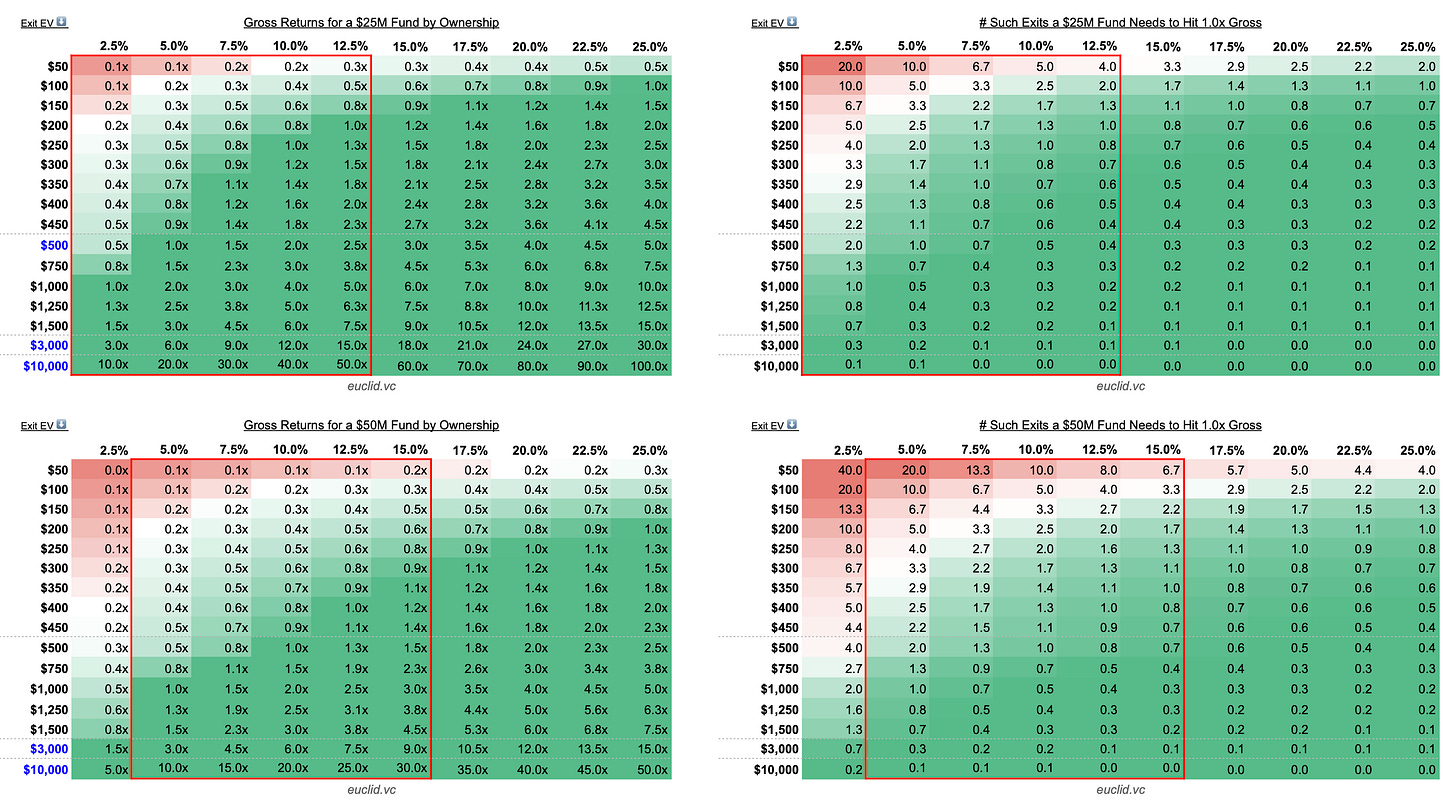

Above, we present a simplified view of the three legs of the alignment stool: exit values (enterprise values5) required to hit 1x and 3x gross, by fund size and ownership stake. The heat-mapping speaks to the historical likelihood of exits of that scale. The greenest shade represents the average VC-backed M&A outcome (EV of $333M). The white band represents the average IPO outcome ($1.3B EV). Red shading represents “grand slam” outcome of $5B+ EV. The red boxes are likely target ownership bands based on AUM.

Off the bat, we can glean a few things:

The math on multi-billion-dollar early-stage VC funds is rough.

Without later-stage / back-up-the-truck strategies, they don’t make sense. Unless the fund can scoop a majority of the venture-backed mega-winners every year… or the $1T IPO becomes a thing.The $1B exit works for everyone, up to a fund size of about $250M.

Interesting that ~$250M is also the commonly cited ballpark for the “break point” where early-stage venture stops making sense (popularized by the Kauffman Foundation’s seminal report).There’s founder value in fewer, higher-ownership VCs on the cap table.

Consider that—holding overall dilution equal—filling your cap table with 2.5-5% preferred owners means something very different from taking one lead with 12%. Smaller stakes need bigger outcomes. Concentrated partners offer greater flexibility to drive a mutually desirable outcome, thereby posing less risk of misalignment.

Overall, you can see how much it actually takes for a single deal to “make” a fund. You can also see how much more likely it is that a single deal “matters” for a high-ownership investor than for a highly diversified one.

How Early-Stage Alignment Changes with Fund Size

“A company that exists for $1 billion post dilution will still return more money to the [big] fund than a small exit. Unfortunately many companies go under during this process.”

— Elad Gil, VC Economics

In our view, the most crucial founder takeaways from this alignment analysis lie in comparing heat maps by fund size. Below, we show two tables: (1) the gross return multiple on a deal based on its parameters (exit size, ownership stake); and (2) the number of such exits a manager would need to return their fund (the most straightforward heuristic; once it climbs above 2-3, that deal profile is a non-starter).

First, let’s look at $25M and $50M funds, likely focused on pre-seed entry points:

While there’s a lot you can read into these charts6, we see a few main takeaways:

Almost no VC will care about sub-$150M exits (beyond finding you a landing).

They can move the needle somewhat for very small funds that have very high ownership—a rarity. If this is your goal as a founder, bootstrap or stick to F&F. If a deal can’t return at 50%+ of a fund7, the only reason the manager is spending time on it is out of dedication to the founding team and their good name (which is extremely important,8 but the economic point stands).Even for a $50M fund, smaller 9-figure exits only work with high ownership.

For a $25m fund owning 7.5-10%, one $250M exit returns (or nearly returns) the whole thing. A $50M fund owning 5% needs four such exits just to reach a 1x gross—not a model they can count on. Note the average VC-backed M&A EV is $333M.Low-ownership micro-funds need $1B+ outcomes as much as big funds.

A $50M fund owning 2.5% needs four $500M exits to return their fund once, gross.9 Not a reasonable strategy, unless they’re very high-volume (in which case, their ability to focus on you as a founder at those outcome levels is constrained). A $25M with the same ownership levels can’t return their fund on a sub-$1B exit. While they’re infinitely more meaningful, they can’t predicate their strategy on moderate outcomes any more than big funds can. And although it’s less likely a tiny fund will ever have a control stake of Preferred, the point stands that just because a fund is small, doesn’t mean they’re necessarily more aligned.

The breakdown of $150M and $300M funds is where it gets interesting.

Exits below $1B generally don’t move the needle for bigger funds.

Simple math. In almost all scenarios, a $750M exit is not a fund-returner.Huge misalignment potential for $150M+ funds with low ownership.

Reasonably owning more than 10-15% as a pre-seed lead is difficult. At 10% ownership, your unicorn outcome would only return a third of a $300M fund. As they grow, most of the best funds evolve their strategy to match their brand and AUM. A friend of ours interned for Insight Partners in 2007—at the time, they considered themselves a Series A fund. While they still are, tens of billions of AUM raised later, they are also a significant player in software & services buyouts. What we’re seeing today is different: early-stage funds growing AUM without commensurate strategy evolution, perhaps due to the perceived difficulty of breaking into the modern Series A landscape. Strategies malformed to capital return needs invite misalignment. Most dangerous for the founder might be the $150M seed manager that flexes on ownership—at 7.5%, they’d need a $2B exit to one-shot return their fund. That likely means one of a few things: deck stacked against mid-range liquidity, baked-in conflict should buying up later prove difficult, or bad signaling & a checked-out GP should they choose not to follow on.Structurally, big funds cannot care about pre-seeds (nor most classic seeds).

Let’s take a $3B exit as an example—an excellent, rare outcome. At 12.5% ownership, a $300M fund would need four of those to broach 3x gross. At 22.5% ownership (which they can buy up to by leading a later round), one $3B exit gets them most of the way there. Moreover, they need to put that $300M to work—$2-3M checks aren’t going to get them there. In sum, logic dictates that big funds only participate in these pre-Series A rounds as an option for later rounds. Because VCs know that, the signaling risk of not leading next time around (whether pre-seed or seed) is considerable.

VC ownership and attention are joined at the hip. This analysis makes it obvious that without 20%+ ownership, even strong exits rarely move a big fund. Given >15% stakes are off-market for pre-seed and most seed rounds, large funds are incentivized to concentrate partner time on later rounds where they can deploy real dollars into more de-risked, multi-billion-dollar bets. And on an individual level, GPs only have so many board slots. It makes sense for them to reserve real calories and social capital for the positions that can return meaningful chunks of the fund.

The reason many founders choose bigger funds at the early stage is brand, yet, as Chris Dixon pointed out on signaling risk: “the danger of taking seed money [from a big firm] is positively correlated with the reputation of the firm.” If that fund’s returns are predicated on buying up and leading later rounds—and they do not—it’s an immediate red flag to other future investors, given they should have asymmetric information on the business. As a GP, the news that another VC passed on a deal is infinitely more discouraging if you know and respect them.

In our view, the most interesting (and fraught) zone today is the $200–300M “seed” fund, which has only become common in the past 5-10 years. For a $50M shop—the historical purview of seed investors—a $300–800M exit at 10–15% can drive 1–5x on the fund. For a multi-$100M “big seed” player, the same outcome is background noise. Meanwhile, a $25M fund spraying 2.5% checks into every hot AI round also ends up misaligned—they can’t justify deep engagement when even a grand exit barely registers and/or a 30+ portfolio is required to make it work. Either that, or they don’t care about the math, which could be good or bad depending on a founder’s outlook.

Any way you cut it, founders: if you go the VC route, someone’s going to end up with a majority of Preferred—and you want that person to be aligned. The way to guarantee that is an awareness of investor incentives and an embrace of conviction, concentration, and ownership.

Never Mix Misalignment and Control

“It’s helpful to have someone along who will call bullshit when it needs to be done... And one fear I have about this world is there’s less and less of that.”

—Bill Gurley, Colossus Interview

Alignment is about a lot more than VC attention. It’s essential to have an investor who cares about you / your company, and one who will spend the time to be additive. The true horror stories of founder-VC misalignment, however, emanate from control.

Founders considering lead investors and syndicates—especially for early equity rounds—should pause to consider how incentives will change as they scale. When a VC takes a board seat, they become a dual fiduciary, responsible to both the startup’s shareholders and their fund’s limited partners. Sometimes, however, those interests diverge. Nor does control stop at the board. 95% of the time, standard VC-financing protective provisions require a vote of the Preferred (among other things) to raise capital, sell secondary, or approve a sale.

There are a number of ways a founder can find themselves stuck, years too late to change the dynamics, even when they take control seriously:

Forced to Swing for Fences: A VC who needs a $10B outcome will always push the founder to “go big or go home.” Of course, what founder isn’t swinging big? And isn’t this right for a VC to do? Maybe not when it takes the form of encouraging hyper-growth before the company’s ready, burn for burn’s sake, or refusing strong acquisition offers. There’s a long trail of companies that turned down major acquisition offers—often with investor encouragement—only to end up with far worse outcomes. Foursquare reportedly had offers from Facebook, Yahoo, and Microsoft, but held out for a bigger future that never materialized. Good Technology, once valued well above $1B, was said to have turned down multiple offers before eventually selling to BlackBerry for $425M, wiping out common shareholders. Fab.com and LivingSocial are similar tales in which investors were said to have pushed for moonshots, passing up sure things.

Exit Blocking and Control: As mentioned, a majority (or supermajority) of preferred stock must approve an acquisition. This means that if a prominent VC (or a syndicate of similar-minded VCs) holds a large portion of preferred shares, they can prevent a sale that the common shareholders might otherwise accept. This can get even more extreme when you consider that the same provisions usually apply to raising additional capital—and more capital, of course, would be often be necessary to avoid an acquisition. Now we’re getting into the breach-of-fiduciary-duty/immediate-lawsuit zone, which is vanishingly rare, but it does put the stakes into perspective. If your lead investor only cares about $1B+ outcomes, they may have the unilateral power to veto any acquisition offers that fall short of that threshold.

Boardroom and Strategy Conflicts: Misalignment often worsens in late stages when investors have more control (board seats, larger ownership) and are eager for an exit, while founders might prefer to keep building (or vice versa). But that path begins with your first equity round and/or first outside board Director seat. In fact, we’d argue it starts before that. “Voices in the room” offer a level of soft control which (per the Gurley quote above) can be incredibly valuable—but also a siren song if out of step. Earlier this year, our friend Rick Zullo at Equal discussed how—especially in more challenging moments, like slowdowns or pivots—misalignment on the board can lead to harmful decisions (even when it doesn’t come down to a vote). Voices in the room matter (for good and for bad)—as a founder, you want those voices to share your incentives from Day One. That’s why alignment on vision is crucial before you accept the term sheet—and why sometimes, you need to read into economics as much as what a VC is telling you.

The sweet spot for early-stage founders should be high-conviction, high-ownership funds (primarily focused on your stage) where alignment is high and you don’t need Decacorn status to mathematically matter.

At Euclid, we are dogged about having skin in the game: a high stake in every company we invest in, at least compared to most peers. As a newer fund, that doesn’t make the job easier. It means we nearly always lead and co-lead, that we don’t “slot in easily” to every round, that we can’t fall back on diversification across a massive portfolio, and that we earn the right to our position on the cap table, every time. However, we believe our approach not only improves returns, but also lays the foundation for a durable VC franchise—while aligning our incentives as deeply as possible with the exceptional founders we back.

Thanks for reading Euclid Insights! Euclid is a VC partnering with Vertical AI founders at inception. If anyone in your network is working on an idea in the space, we’d love to connect. Feel free to DM us here or on LinkedIn.

Sapphire’s analysis only considers priced rounds in NYC and SF. Also, given that the range of the chart above includes $1-5m rounds, we assume some pre-seeds are grouped in with seeds (though given the prevalence of SAFEs in <$10M rounds these days, many relevant data points are excluded). Also, while Sapphire doesn’t include an explicit definition, a fund is commonly recognized as “mega” if it has, at minimum, $1B+ AUM. You can find more data from their report here.

We aren’t sure how Sapphire categorized their data, but it’s worth noting that extensions, bridges, or opportunistic raises may be included.

For simplicity, we’ll mostly refer to gross returns in this article. The difference between gross and net are fees (carry and management fees). VCs typically articulate their targets in net returns, which are always lower than gross—meaning that the numbers we throughout this essay are overly conservative. I.e. if anything, misalignment potential is understated.

Christophe Janz from Point Nine summarized signaling risk well in a piece 10 years ago, describing the case wherein a Series A fund invests in a seed: “What this refers to is the situation that arises when you want to raise your Series A round and your VC doesn’t want to lead. In that case, any outside investor who you’re talking to will wonder why your existing investor – who as an insider has or could have a great understanding of the business – doesn’t want to invest. Everybody in the market knows that if a large VC invests small amounts the purpose is optionality, so if the VC then doesn’t try to seize the option, people will wonder why.”

Throughout this piece, we’re using EV = Enterprise Value. While that’s not the same as Exit Value, it effectively is for our purposes here.

More context on the heat-mapping: dark green band represents a 1x+ return of the fund—it only takes 1 (or fewer) of such deals to return the whole thing. Naturally, VCs care about those the most. The closer you get to red in the heat map, the more the deal profile becomes untenable for the fund—they’d just need too many of them to drive good returns. It’s a proxy for how much the GP should care about such deals, given their size and ownership.

For small funds, most GPs care about fund-returners. For platform funds with many deal-makers, they may be more comfortable targeting some 20%-returners and some bigger swings with more right tail. All numbers illustrative but you get it.

Which, for what it’s worth, is not an insubstantial incentive. Fred Wilson wrote a great piece years back on why spending time on the “long tail” is actually a logical manager choice, if you consider the importance of brand and reputation in VC. Many of us (including, I’d like to think, Omar and me here at Euclid) are in VC because we love startups and founders as much as anything else—human relationships are our lifeblood. That said, the investment world sees its fair share of unscrupulous behavior and, as a founder, it’s worth knowing how everyone’s bread is buttered.

Thank you to Grayson Judge for pointing out a typo in our original math here!

Enjoyed the read. You’re describing the part of the industry everyone else tiptoes around: once capital floods the system, the only strategies that work are the ones that don’t depend on power-law scarcity.

When a system gets overcapitalized, the social contract gets rewritten.

Early-stage investors stop hunting for outliers and start hunting for anything large enough to absorb capital. Founders stop building companies and start building the performance that keeps misaligned capital calm. Mid-range exits, once the backbone of the ecosystem, become collateral damage.

Great analysis!