The Unknown Known

What founders can learn from Donald Rumsfeld

There is an excellent 2013 documentary by Erol Morris, The Unknown Known, addressing the failures of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld through the lens of his relentless memo writing. The title of the film comes from an infamous answer he gave during a 2002 press conference:

Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.

In The Decision Book (2012), author Mikael Krogerus referred to this as the Rumsfeld Matrix, building on a framework that had emerged within NASA decades prior.

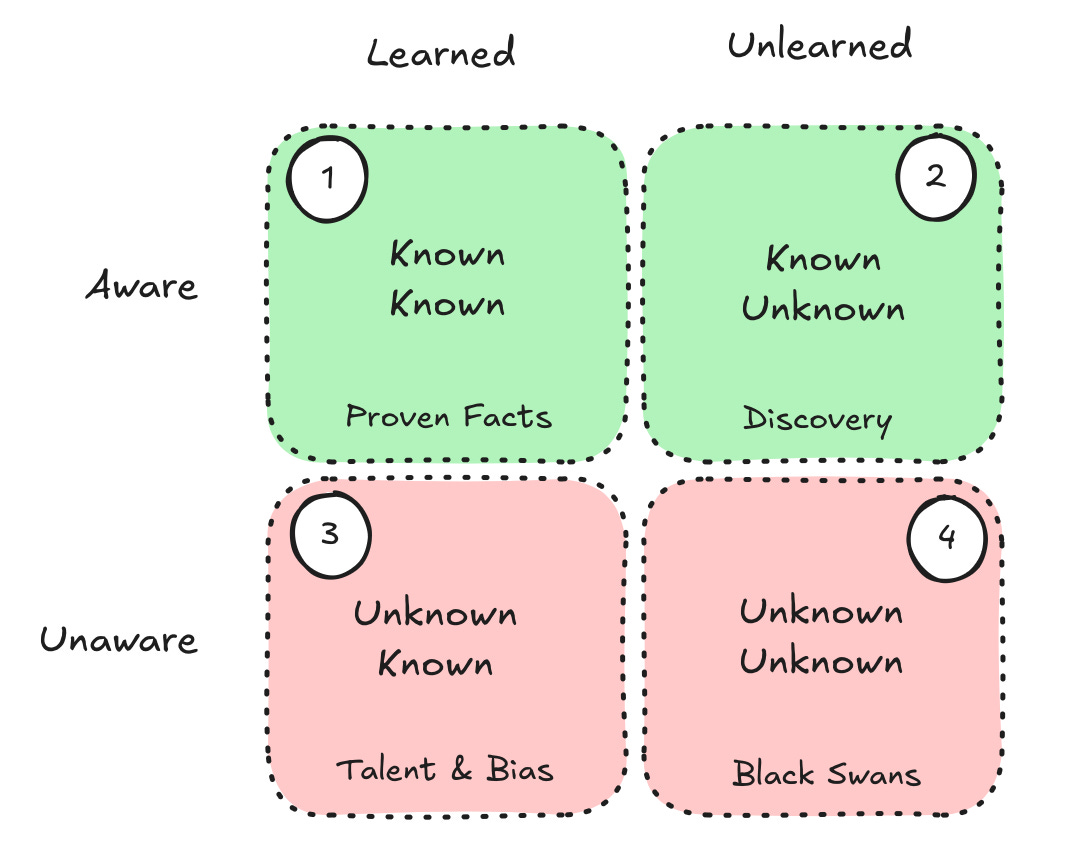

The Known-Unknown Matrix is a helpful heuristic for all operators, but here, we’ll focus specifically on early-stage vertical software founders.

Known Knowns comprise the domain experience and hard knowledge necessary for sound strategic planning and decision-making. They are facts, lessons, strategies, playbooks, or actions a founder knows well enough to implement within their own company, should they be necessary. A founder must accumulate sufficient Known Knowns about their market and customers to achieve PMF.

Known Unknowns are problems, questions, or knowledge gaps that a founder is aware of but has yet to solve—or is unsure whether they need to. They are the focus of hypothesis testing and discovery on the path to product-market fit, with the goal of converting impactful areas into Known Knowns.

Unknown Knowns are elements a founder isn’t aware of yet in the context of the business but that are already known by the team. These can be talents that only show in turbulent times or pernicious biases hidden in times of success. Presumably, Morris chose this as his documentary title because it encapsulates biases or subconscious attitudes he was hoping to shed light on in Rumsfeld’s case. Founders should manage this category by bringing on well-suited executive hires (e.g., sales, customer success, etc.), building a broad network of advisors, and maintaining continual self-awareness of their bench strength.

Unknown Unknowns represent the truly unpredictable—black swans. While founders can and should focus on building organizational resiliency to manage potential fallout from Unknown Unknowns, they are (by definition) completely unforeseeable.

Staying Ahead of Unknowns

We have discussed at length our emphasis on founder-market fit investing at first-check. The numbers bear what we believed to be true qualitatively: teams with an industry insider capture 84% of the total exit dollars in Vertical Software. Having the largest surface area of Known Knowns with vertical-specific domain experience is a competitive advantage. The top three benefits we see:

Understanding nuanced stakeholder relationships, physical workflows, buying patterns, and the parlance of decision-makers in their vertical informs wedge product selection and drives behavior change.

Leveraging credibility and relationships to lock in early users and partners.

Attracting industry-specific talent is often necessary for G2M, BD, support, ops, and sometimes even product roles.

Beyond the founding team, the pace and scale of reaching various stages of product-market fit are ultimately a repeat exercise of addressing Known Unknowns through hypothesis testing and validation. In our previous essay on identifying levels of product-market fit, we highlighted three conditions—urgency, scalability, and repeatability—that teams should focus on. A founder with deep domain expertise should have a strong awareness level beyond their personal Knowns, giving the company a head start in customer discovery.

Of course, as founding teams reach various stages of the framework, they will identify Unknown Knowns and emerging knowledge gaps as they aim to scale their organization. Most often, these can be filled by the first executive hires in sales, CS, technology, and/or product. Great founders will recognize these gaps early before they drag down progress and potential growth. Moreover, their industry experience should give them an advantage in finding the right talent to address Unknown-Knowns—even if they aren’t coming from industry, all successful vertical execs must to some extent “talk the talk” of the space.

Ignore the Unknown Unknowns

The Known-Unknown Matrix is a way to break the pursuit of product-market fit down into two key motions:

Building out a strong team & network to accrue Unknown Knowns (box 3) and uncover Known Unknowns (box 2)

Establishing an efficient, effective experimentation process to shift key items from Known Unknown (box 2) to Known Known (box 1)

Equally, however, the framework is an excellent guide on where not to spend time.

While it’s often said that every great founder has a degree of paranoia, navigating to PMF at the earliest stages requires relentless focus. Could you get crushed by a larger competitor calling a surprise audible to move into your space? Possibly. Is there a team in deep stealth building a better product? Potentially. But those are ultimately distractions from the core mission in pursuit of product-market fit. Will macro shifts next year dampen demand for our offering? Your guess is as good as mine. These are true Unknown Unknowns and are not worth spending time on when time and organizational resources are scarce.

This is not to say a founder shouldn’t always be learning and testing. Are you going after the right ICP? Is your pricing appropriate for that segment? Can I acquire them efficiently? How do adjacent customer segments feel about my product? Well, these are all testable Known Unknowns—questions like these, and the process of moving them to Known Knowns, should dominate the mindshare of early-stage teams.

Be Less Like Donald Rumsfeld

While some have called this framework the “Rumsfeld Matrix,” we believe the former Secretary misused it disastrously. Unknown Unknowns are dangerous not only because of their unanticipated impacts but also because of the fruitless time and energy wasted attempting to anticipate them. Rumsfeld’s efforts to stay in front of Unknown Unknowns were deleterious to the US defense organization. Resources that could have been spent on filling knowledge gaps and stress-testing assumptions were instead devoted to endless scenario planning and predictions for the unpredictable. Rumsfeld would describe 9/11 as a “failure of imagination” rather than a failure of US intelligence. When commenting on the entirely predictable lack of law and order in post-invasion Iraq, Rumsfeld remarked, “stuff happens.” Morris’ documentary highlights a quality we believe founders should avoid at all costs: the conflation of preparedness and execution. Both are ostensibly good. But the former is an infinite exercise with no measurement of success. The latter focuses on tangible problems and experiments that can be controlled, producing results.

Rumsfeld frequently invoked the lack of foresight as an excuse for adverse outcomes when a clearly Known Unknown was the more tangible culprit. For several years following the invasion of Iraq, Rumsfeld refused to acknowledge that there was an insurgency—despite happenings on the ground fitting that definition to a tee—and ordered his staff not to even use the word. Although many experts anticipated that outcome, he was so tied up in the analyzing iterative chain of future possibilities that he overlooked some of the most prosaic likelihoods. The touch of paranoia common to many high-level executives spun a bit out of control, most humorously on display in memos like “Issues w/ Various Countries,” since famous for its incomprehensible scope and unclear demands.

We don’t want to downplay the importance of foresight in a CEO’s job. They are the person in the organization who has the most leeway to think months and years out to make critical strategy decisions. What we counsel here, however, is ensuring this long-term thinking does not come at the cost of near-term focus and execution. Occam’s Razor suggests why we should start with the simple, tangible, and focused. Suppose a competent team is spending all day working on a problem. In that case, the most common-sense roadblocks are probably not so foreign—they are likely Known Unknowns you are overlooking or knowledge gaps that can be filled with the help of appropriate talent.

Reject Complacency

Over the long haul, spending too many cycles on Unknown Unknowns can lead to the atrophy of accountability in a startup. The most beautiful stories of product-market fit rhyme with the scientific process—testing what works, running into some walls, achieving significant breakthroughs, and being rewarded by your market for nailing it. The team formulates a hypothesis, tests it, synthesizes it based on results, and so on. By contrast, no team can produce an actionable result by “working on” a Black Swan. Knowing the goalposts one is working against is critical to team, resource, and time management—a CEO should set appropriate constraints within which operator creativity can flourish.

Expecting some honest reflection or self-awareness, Unknown Known interviewer Morris asked Rumsfeld what lessons he learned from Vietnam. Through the 1960s and 70s, he watched the Vietnam War unfold as a congressman, an ambassador to NATO, and finally, a White House chief of staff. Rumsfeld responded:

Some things work out, some things don’t. That didn’t.

If that’s a lesson, yes, it’s a lesson.

Unknown Unknowns are a black box of FUD that spawns endless dilatory projects. And since no final, actionable results can ever be obtained from them, no lessons are learned, and no one is responsible for failure or success. The ultimate result—the most dangerous of all for founders—is complacency.

Thanks as always for reading Euclid Insights. For more suggested viewing and reading, check out the rest of our sources here.1 Please reach out or share feedback in the comments below.

Morris (2013). The Unknown Known

Krogerus (2012). The Decision Book

Kaplan (2014). Seeking Truth in a Blizzard of ‘Snowflakes.’ New York Times

Hornaday (2014). ‘The Unknown Known’ review: Documentary lets Donald Rumsfeld have his say. Washington Post

Milbank (2005). Rumsfeld's War On 'Insurgents.’ Washington Post

Great read. Thoughtfully and analytically written. Excellent insights as well as writing and the comparison to Rumsfeld, an interesting one.