Diffusion of AI Across Vertical Markets

Vertical Workflow Architects needed to fill the Adoption Gap

The discourse around AI adoption tends to oscillate between two poles: breathless proclamations that AI will replace all knowledge workers by the end of the decade and hand-wringing that enterprise AI pilots are failing and not delivering value. Both narratives miss the mark. The reality is more nuanced and, frankly, more interesting. And while most narratives tend to focus on the cutting edge of frontier models, the pursuit of AGI and/or consumer adoption, we are particularly interested in the diffusion of LLMs within vertical markets.

In this essay, we’ll share our vision for the near-term future of Vertical AI adoption, using two frameworks:

Rogers’ “Diffusion of Innovations” model, explaining how technologies spread.

Evans’ “Absorb / Innovate / Disrupt” model, which aims to illustrate what shape that diffusion takes as real-world products hit the market.

Diffusion Theory + Vertical Markets

American sociologist Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations, published over 60 years ago, is still a widely influential model for understanding how new technologies diffuse through society. Rogers outlined five key factors that influence the rate of adoption of an innovation: relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, observability, and trialability.

Generalized LLMs perform strongly on several of these dimensions. The relative advantage is significant, as tasks that previously required hours can now be completed in minutes. “Trialability” is high, with platforms such as ChatGPT or Claude available for free experimentation. The results are immediately observable, allowing users to assess outputs in real time.

However, compatibility and complexity present distinct challenges, particularly within vertical markets. Compatibility concerns how well an innovation aligns with existing values, behaviors, and tools, while complexity refers to the learning curve required for effective use. For example, marketing teams generating blog posts may find both compatibility and complexity manageable. In contrast, construction project managers who integrate AI into workflows for scheduling, subcontractor communication, regulatory compliance, and site conditions face significant compatibility challenges. Here, complexity extends beyond prompt engineering to the broader task of embedding AI into established work processes.

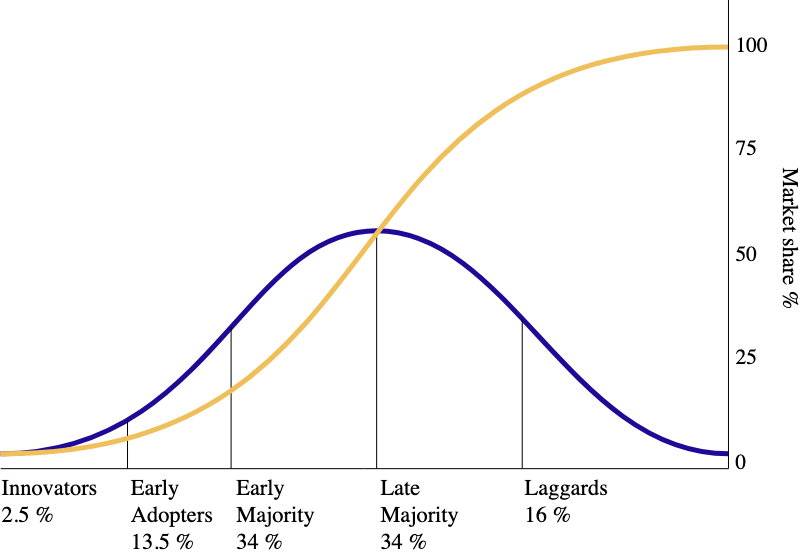

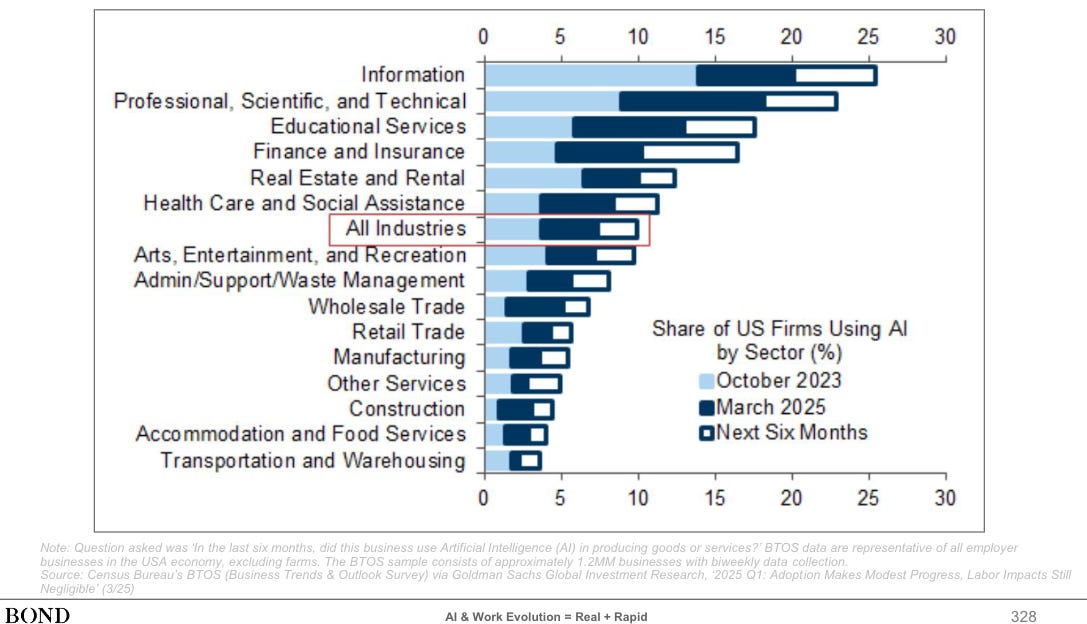

Rogers also described the S-curve of adoption, which begins with innovators and early adopters, followed by the early majority, late majority, and laggards. He emphasized the existence of a “chasm” between early adopters and the early majority. Early adopters are willing to tolerate friction, incomplete solutions, and improvisation, whereas the early majority prefers plug-and-play solutions. In the context of generalized, consumer-facing LLMs, chatbots appear to be transitioning from early adopters to the early majority. Depending on survey methodology, approximately 10-15% of US consumers report daily chatbot use. Ramp’s internal benchmarking indicates that about 45% of US businesses have a paid AI tool subscription, yet many traditional sectors remain laggards in adoption.1

Although most vertical markets are experimenting with AI tools, current evidence suggests that adoption is still squarely in the Innovators phase. Bridging the chasm will take more than marginal improvements in model quality—it requires aligning technology with how real work actually gets done in these industries.

In other words, verticals are not lagging because AI’s potential is low or unwelcome. The challenge is instead that the current wave of AI tools is still mostly contorting itself around existing workflows, rather than reimagining and reshaping them. In some ways, this is a necessity—entrenched human familiarity with the old ways takes time to break. To understand how Vertical AI accelerates in the coming years, it’s worth examining what true workflow innovation—and eventually disruption—would look like.

Phase I: Absorb

Automate the Existing Workflow

In Ben Evans’ latest presentation, AI eats the world, he introduces a framework for how adoption of transformative technology follows a predictable pattern: Absorb, Innovate, Disrupt. While Ben applies it to the broader LLM landscape, the same framework applies equally to Vertical AI.

Absorb: Automate obvious use cases by making existing processes faster / cheaper.

Innovate: Create new products and (un)bundlings that were previously impossible.

Disrupt: Redefine the question entirely.

If Rogers’ Diffusion framework helps explain how innovations spread, Evan’s A/I/D helps explain what form that spread tends to take. In other words, diffusion isn’t just about speed—it’s about the sequence of or extent to which workflows are impacted, considering where we are in an adoption cycle.

In the Absorb phase, organizations integrate the new technology into existing workflows. For example, early spreadsheets replaced adding machines, and email supplemented traditional mailrooms, with each technology fitting established mental models. The most successful generative AI use cases today, such as coding assistants, marketing content generation, and customer support automation, exemplify this phase by accelerating existing workflows.

The same is true in successful Vertical AI: the dominant use cases today are centered on situations where today’s generation of LLMs can automate an existing workflow with “good-enough” accuracy. As we talked about in our introductory piece, Emerging Playbooks in Vertical AI, successful early breakouts largely follow this pattern:

Identify an impactful constraint to revenue that AI can meaningfully address.

Serve as the authoring layer (i.e., launch point) for a valuable internal workflow.

Power the workflow in a way that unlocks revenue—perhaps agnostic to peripheral systems to start, but progressively absorbing downstream.

The authoring layer today, because of both LLM-performance constraints and the limitations of workflows where there are automatable Absorb use-cases, broadly falls into two discrete buckets:

Documentation: Voice and/or text-based inputs into an async document-centric workflow (e.g., EvenUp and demand letters; Abridge with EHR notes; Rilla with sales transcripts & coaching)

Customer Communication: Workflow where phone remains the preferred medium for sales, supports, and ops, while calls are constrained in length and complexity with a pre-defined range of outcomes (e.g., Assort Health for patient phone calls; HappyRobot for logistics operations; Toma for car dealerships)

And here’s the key insight: despite the Absorb use cases being what we would consider more ‘superficial’ opportunities, we still have enormous room to run with many massive companies still to be built. As covered in our piece on the AI infra boom:

Even without further meaningful improvements in foundational models, the installation phase of current gen LLMs across vertical markets represents a generational opportunity in itself. — Euclid Insights, Deus Ex CapEx

We see two main frictions to moving past the Absorb phase today: (1) human capital (which includes human behavioral and psychological speed-bumps); and (2) integrations (specifically, incumbent systems of record whose fear of disruption leads them to slow down connectivity intentionally, and accessing data that exists in hard-to-access systems and formats today). The human capital constraint is perhaps the more binding of the two. It’s also a reminder of why Vertical AI requires a rare combination of technical acumen, entrepreneurial skill, and domain expertise. A healthcare AI startup needs founders who understand clinical workflows intimately—not just abstractly. Such expertise is scarce and unevenly distributed.

Integration presents a different challenge. Legacy systems of record are often fragmented, inconsistently formatted, anchored by institutional inertia, and rife with incentives that can undermine connectivity and openness. Free and open data within a vertical workflow would open a whole set of new use cases and markets. Today, however, there is a penumbra of challenges in system integration beyond sorting APIs. Perhaps it lives in a customer’s system of record. Maybe it lives in a non-software, third-party service provider. Perhaps it doesn’t even exist outside tribal knowledge and unrecorded conversations. Vertical businesses need frictionless AI solutions that outperform SaaS in UX—but these same businesses also often lack the internal IT resources to implement new products to the fullest.

This is the essence of Absorb: AI makes the current system cheaper, faster, and more tolerant of inefficiency, but it doesn’t challenge the system’s shape. That’s why it slots in quickly—but it’s also precisely why it only gets you so far.2 It’s also why, in our estimation, we see such high-archetype clones of early vertical winners (scribes, voice-answering services, document generation, etc.). At some point, marginal gains from faster discovery or human loops made obsolete hit diminishing returns. A bigger opportunity—and the next wave of diffusion—arises when entrepreneurs look beyond optimizing the legacy workflow and instead use AI to reshape it. That inflection point is where the Innovate phase begins.

Phase II: Innovate — Authoring Layer & Beyond

In the Innovate phase, new products emerge as entrepreneurs bundle and unbundle offerings, discovering novel combinations. This is when the market recognizes that the technology enables previously impossible solutions.

There are only two ways to make money in business: One is to bundle; the other is unbundle. — Jim Barksdale, COO of NetSpace (1995)

Historically, new platforms have led to new tools, increased unbundling, and the creation of entirely new software markets. Each computing platform—mainframes, PCs, SaaS, and mobile—unbundled previous generations and introduced new categories. Mainframes provided a few core applications, PCs enabled dozens, and the SaaS era brought hundreds.

What can the LLM era enable? We touched on this question briefly in a past essay:

It’s critical we consider what LLMs can enable that a previous-generation SaaS company couldn’t. In our view, the answer here comes down to friction. Both SaaS-first and AI-first vertical products target high-value workflows. SaaS, however, inherently requires the adoption of a new UI, including training and perhaps even market education. Vertical AI wedge products, however, can leverage natural-language interfaces to reduce or even eliminate the adoption curve. What is easier to adopt than a solution that mirrors your existing workflow, but instead makes the calls or intakes the customer info on your behalf? — Euclid Insights, Emerging Playbooks in Vertical AI

Two of the clearest near-term Innovation-phase opportunities are voice-first and text-first Vertical AI applications. These enable agents to transform how businesses interact with their customers and employees. Moreover, the best of these start with an authoring layer3 which, as we detailed in the essay above, is fertile ground for the eventual displacement of incumbent systems of record.

Today, building a successful, vertical-specific voice product that is not only high-quality and reliable but also customers can trust to handle the most critical aspects of their livelihood remains largely out of reach. Of course, improvements in the performance and reliability of voice-infra are progressing rapidly. As such, we believe the voice opportunity is substantially larger than the current scope of phone-based operations would imply.

The power of humans and voice AI in combination comes down to bandwidth. Software UI has been a dilatory, constraining second language that limits the throughput of thought and action. Many across vertical workforces have barely had time to learn this “language”—what could they do if we empowered them to operate in their native tongue? How many millions will be voice-native users of technology?

The opportunity for text-based vertical AI also has a long way to run. Simple document parsing or creation (perhaps replacing BPO spend) is fertile, but only the beginning. The next phase, we imagine, will focus on contextual understanding. Building a corpus of data around a problem—with human-in-the-loop feedback simplified by LLM UI—that an agentic workflow can reliably, accurately complete valuable tasks. Reinforcement learning, specifically simulating workspaces where agents can be trained on multistep tasks, should be well-suited to tackling higher complexity workflows.

In a way, what many envisioned with earlier iterations of machine learning is now made possible through natural language AI. As we’ll touch on below, however, complex vertical use cases will require much more nuanced interfaces (or at least implementations) than a simple self-serve ChatGPT-style text box.

We would argue that the most pressing constraint today is simply that it takes time for entrepreneurs, especially in vertical markets, to discover the novel combinations that are truly a step beyond the classic absorb use cases. Integrations with existing systems of record remain a real bottleneck in many verticals. Nevertheless, developing genuine, innovative vertical AI requires understanding not only what AI can achieve in the short- and medium-term, but also precisely how technology can transform existing workflows.

Taken together, these advances in voice, text, and contextual understanding represent more than better UI. They create entirely new legs of a vertical workflow, offering leverage over existing systems and, in some cases, replacing legacy point solutions. This is the heart of the Innovate phase: new products and (un)bundlings that extend and free up the old workflow. But even this stage still assumes the process remains more or less the same. The next phase does not: Disruption begins when the system subsumes or re-envisions the vertical workflow entirely.

Phase III: Disrupt — True Systems of Action

Disruption occurs when the fundamental question changes from “how do we do this faster?” to “why were we doing this at all?”

The vertical markets that account for the bulk of economic activity—real estate, construction, manufacturing, logistics, transportation, and even portions of health care—remain slow to adopt LLMs. Not because the technology can’t help, but because the work of making it a must-have rather than a nice-to-have is still in progress. In our view, the disruption use-cases are the ones that will ultimately justify the immense CapEx spend on LLMs. They will be fundamentally transformative to how businesses and industries operate.

One persistent challenge in vertical AI adoption across these markets is the interface problem. The ubiquitous chat box with its blinking cursor—” ask anything”—feels like an invitation but often functions as a barrier. In some vertical markets, the challenge is highly constraining but manageable. In most markets, however, the problem is existentially limiting. A construction project manager doesn’t need to “ask anything.” They want their scheduling conflicts flagged, their change orders processed, and their RFIs routed to the right subcontractor. The blank canvas of a general-purpose agent offers too much freedom and not enough structure.

Voice interfaces help somewhat—they’re more natural for field workers. But they broadly address access to AI, not the fundamental question of what the AI should do. Today, they are still optimized for absorb-phase use cases: dictation, information retrieval, and simple commands. In vertical AI, users don’t want to “browse” or “explore, they want work completed. Voice may simplify the input of such a query, but it’s no closer to building a system of action that is transformational for productivity. They want the software to know already that the HVAC sub is delayed, develop a remedy, and loop in a human for approvals as needed.

Beyond voice, however, performant multi-modal AI across voice, vision, and text opens a much wider aperture of opportunities, not just by expanding the work-to-be-done, but also by enabling possible UX interfaces beyond simple text and voice. Most real-world physical industries are multi-modal in nature: encompassing contracts, 3D designs, and blueprints, with highly collaborative workflows occurring over email, phone, and even in person on manufacturing floors, construction sites, and customer homes. A more innovative chatbot, a better knowledge management tool, or even an intelligent voice assistant will not solve the core constraints required for true transformation.

Furthermore, there is much work to make implementation repeatable and functional: how do we collect all the data needed to make this system comprehensive, reliable, and accurate without overburdening the customer or committing to endless integration work? Could advances in reinforcement learning, especially within highly specialized vertical workflows and datasets, help bridge this gap? Could multi-agent systems with proper guardrails and training help close the reliability gap in these industries?

Regardless of input and output, the critical shift and upsize in opportunity size (and outcomes) will be in moving beyond workflow accelerators to end-to-end workflow completion. There is still some distance away from having the conditions for this phase to emerge:

Foundational Improvements: Certainly, improving accuracy, performance, and trust. But also, net-new AI developments are required. Multi-modal AI—to help expand the attainable surface area of prospective “work-to-be-done”—is still in its infancy. The same goes for deterministic needs: whether that’s simply reducing hallucinations, multi-agent redundancy, or some other real-world remedy.

HCI: We need software that can handle complete workflows without requiring user input or supervision, yet remains observable. First, that means helping simplify the broad set of UX challenges that exist (“solo text box” doesn’t cut it). Second, we need systems that continually learn from human partners and retain that knowledge long-term.

Interoperability: We need more scalable workarounds for the system-of-record integration challenges highlighted previously. We need AI systems that can collaborate more readily, without intensive MCP projects. Browser agents are a helpful start and will undoubtedly improve, but they often feel like putting a Band-Aid on a gunshot wound.

This is the leap that would make all the ongoing GPU spend rational: disruption-phase use cases, where AI moves from accelerating workflows to owning them end-to-end. That future won’t be built by generalists building better wrappers or tweaking prompts; it will be built by obsessed founders with the credentials to understand and redesign the work itself.

WANTED: Vertical Workflow Architects

This brings us to the final and most crucial rate-limiting factor to Disruption-stage Vertical AI: the humans building these products. That’s why we focus so much on teams at Euclid! Not just brilliant, talented individuals—people who truly understand their markets. Maybe the Y-Combinator-like model of launching hundreds of cohorts of talented young engineers into various vertical markets each year is enough to bridge the talent gap. Interestingly, YC founders have become much younger in recent years (remarkably, 50% of Y-Combinator founders are under 25).

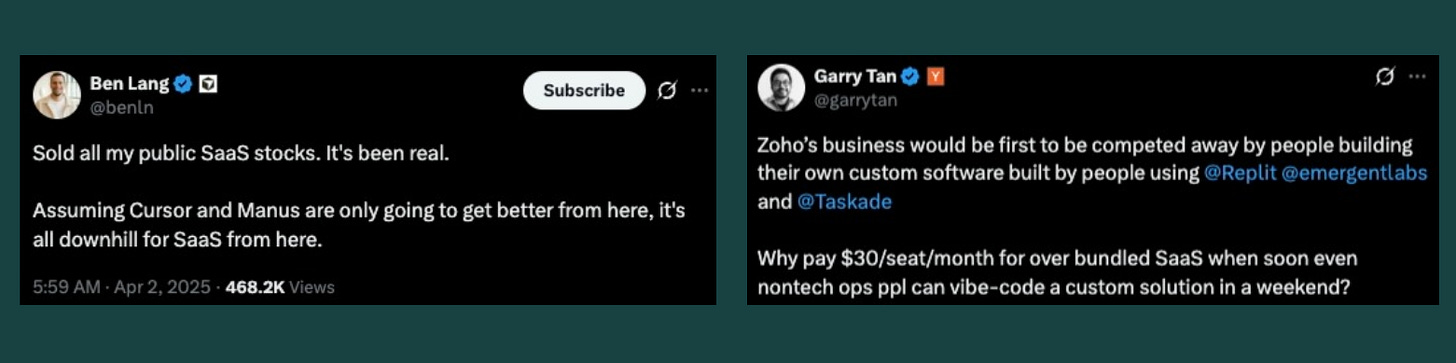

Still, both our experience and the empirical data suggest otherwise. We think this truism will be even stronger in the Vertical AI era. It’s not about age, but knowledge. Put another way, to generate the economic value necessary from the LLM bet, we are currently under-indexing on vertical workflow architects. There is a widely held belief that if we get a better model—GPT-5, Claude 4, etc.—these problems will vanish. That is the “Mainframe -> PC -> SaaS -> Mobile -> AI” inevitability argument. We assume the utility will happen! Software can be built by anyone and everyone, and solve any problem.

History, of course, suggests otherwise. The platform transformations of the past few decades led to the unbundling of everything from software to commerce. The emergence of SaaS many years ago made it possible to deliver core business tools over the browser, eliminating the need for users to handle installation, upgrades, or maintenance, and radically changing how software was bought and sold. Eventually, founders realized that the economics of SaaS produced white-space opportunities to build software for vertical markets. Every vertical operates differently: a construction company, a yoga studio, and a restaurant each have their own distinct workflows. Unlike horizontal SaaS, which targeted broad use, vertical entrepreneurs immersed themselves in the unique logic and language of a single industry.

Toast was founded in 2012, betting on the eventual ubiquity of mobile devices and on improvements in cost/performance that would enable its business. ServiceTitan was founded in 2007, but it was not until they shifted to the Cloud (2012) and eventually Mobile (2015) that the company reached escape velocity. The ubiquity of mobile devices and third-party delivery apps was a significant tailwind for Slice, enabling it to eventually deliver an all-in-one digitization tool for pizzerias to maintain relevance in an increasingly mobile-first ecosystem.

The transition to AI is unique in that it unbundles the work itself. To capture this, we need more than just teams that can fine-tune a model or “translate” a horizontal application to a vertical one. We need teams who understand the visceral, boring, day-to-day constraints of a specific vertical so profoundly that they can deconstruct it. As technology advances in functionality and reliability, the unbundling of work can begin, and the transformation will truly begin.

Disruption demands domain expertise. But it also requires someone who can hold both sides of the problem at once: the lived reality of the vertical and the instincts of a technologist who knows what it takes to cross the chasm and produce venture-scale change. Vertical Workflow Architects are the key to bridging from Innovators into the Early Majority. Without them, we’re just piling up better models against the same old broken workflows, distribution challenges, and adoption bottlenecks.

The Case for Extreme Optimism

We are AI investors, ourselves, of course, so we are certainly not pessimistic about the immediate opportunity in front of us. We remain cautious about the seemingly close-your-eyes-and-hope assumptions that many are taking in this market. We are still early. It feels analogous to the “Mobile Internet before the App Store” moment. We have the connectivity (LLMs), but we are still trying to browse the web on a flip phone with middling connection speeds. The longer-term case for optimism remains, despite short-term bottlenecks that need to be addressed.

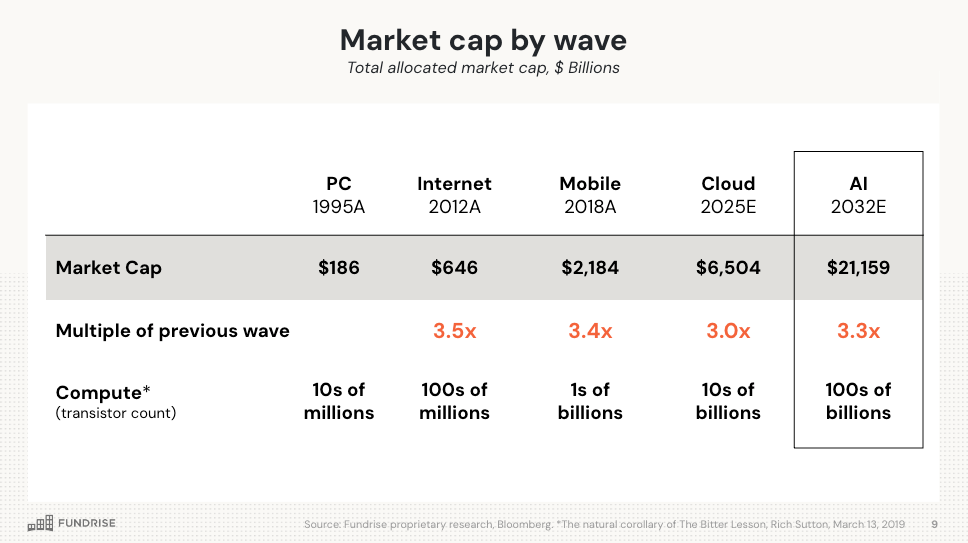

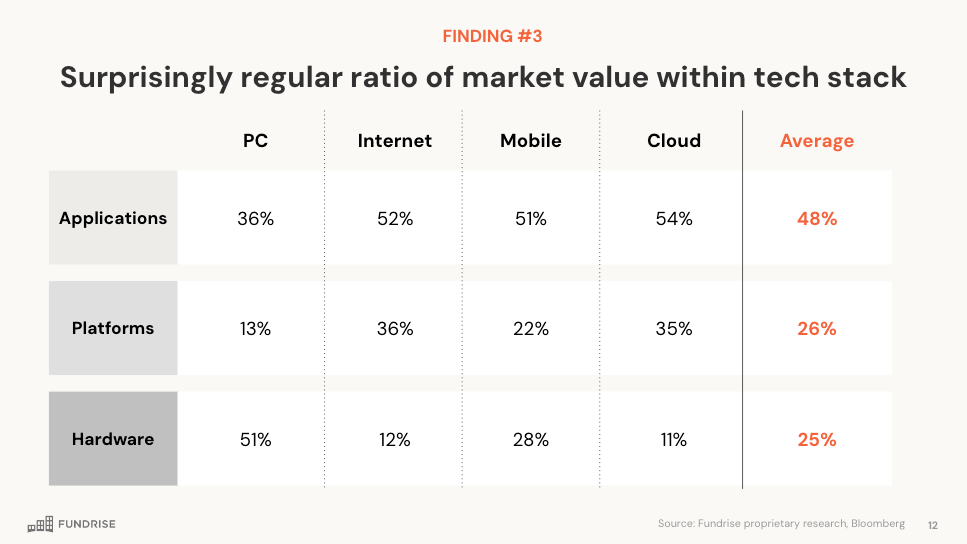

Fundrise analyzed 40 years of data, showing a consistent expansion in market cap across successive tech eras—from PCs to the Internet, to Mobile, to Cloud—and suggests that AI might follow suit. Their conclusion was two-fold: 1) a roughly 10x increase in compute power typically unlocks an innovation wave; 2) each innovation wave creates a market size roughly 3x larger than the previous one. For AI specifically, the rule of three suggests the aggregate market cap would exceed $20T.4

Their analysis also examined the value capture by segments of the tech stack. On average, applications capture roughly half of the total value creation, while platforms and hardware each capture approximately 25%. Applying those figures to the aggregate AI market cap suggests a $11T opportunity in applications and roughly $5B in hardware and platform.

We are still so early in the transformative impacts of this platform shift. When James Watt improved the steam engine’s efficiency, coal consumption went up, not down. Cheaper energy made more uses economically viable. This dynamic—often called Jevons’ paradox—is central to understanding AI’s trajectory, especially in vertical markets.

Consider healthcare administration. The conventional framing asks whether AI will replace medical coders or prior authorization specialists. But the more interesting question is what happens when the cost of processing a claim drops >90%. What happens with even higher levels of value capture? For example, what happens when AI can predict and avoid costly emergency room visits accurately?

In a sense, AI acts both as a productivity booster and a bottleneck creator. In other words, when you remove one bottleneck, the pressure shifts to the next. A simple example is coding assistants. Developers can produce code faster! Big win, right? Except that the bottleneck shifts. Because developers can quickly produce large amounts of code, code reviews are the new constraint for shipping code. So, for actual sustained productivity gains in output, you now need AI to automate the reviews as well.

It is these comprehensive end-to-end agentic transformations that are essential to fully revolutionize vertical markets and fulfill the economic potential of LLMs. As such, for founders developing in vertical AI, the hard work must be highly specialized and market-centric. No doubt, technology will continue to advance, but we need vertical builders to see and build the future. The well-known Bill Gates axiom, “most people overestimate what they can do in one year and underestimate what they can do in ten years,” feels particularly relevant here.

Timelines in Vertical AI (or AI generally) are inherently uncertain. Frameworks phases—from absorb to disrupt, or early adopter to majority—are inherently low-resolution. Improvement of foundation models, though essential and inevitable, is not a guarantor of the rate or speed of adoption. The more interesting current question, in our view, is how quickly Vertical Workflow Architects can reimagine the future, producing enormous value creation and category-transforming companies along the way. And our hope at Euclid is that we’ll be fortunate enough to partner with a few of those entrepreneurs and play a small part in supporting those journeys.

Thanks for reading Euclid Insights! If you’re building (or thinking about building) in Vertical AI, we would love to connect. Reach out via LinkedIn or email.

So far, in this context, refers to a limited scope in terms of breadth and depth of opportunities, not the size of the outcome.

The “Authoring Layer” speaks to an AI wedge product that is the first step in a vertical workflow. This could be a sales conversation, a manufacturing design, an invoice review, or a healthcare consultation. Because it is the “first touch,” it less often requires substantial integrations with pre-existing SaaS systems of record (because it hasn’t been entered as an object yet at that step). The AI solution often creates something a human would create—documentation, notes, a lead, an appointment—and hands it off to the existing system (e.g., CRM, ERP, PMS, EHR) as a human would. You already have a sense of what startups might build beyond the Authoring Layer... just follow the workflow. Eventually, that road could organically lead to wholesale SoR replacement.

Fundraise - What will AI be worth?

Rogers (2003). Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition

The SMB sector is one of the most exciting spaces to observe verticalisation. Thanks to AI, SaaS products are being reshaped from the ground up, pushing them toward verticalisation and tighter alignment with real business workflows and customer needs.

That has created a massive vertical AI opportunity: owning the full workflow through custom-built agents that actually get the job done.